Context

We partnered with British Columbia’s Office of the Representative of Children and Youth to make visible the lived realities of young people with experience of family breakdown — whether because of contentious divorces (through the Family Law Act) or because of removal into the child protection system (through the Children Family and Community Services Act.

Our goal was two-fold: to show how (1) lived experience can shape public policymaking, and (2) the collection of lived experiences can be an intervention in and of itself, affirming youth agency and voice.

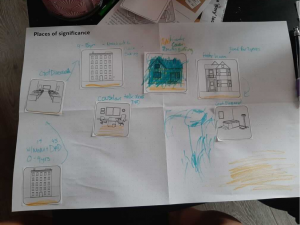

We bear witness to lived experience using ethnography. Ethnography as a practice is rooted in place, in immersing oneself in the unique and particular contexts of individuals to better understand their perceptions and world views. Ethnographic research can produce rich, descriptive qualitative data that paints a holistic picture of a person – where they live, how they interact with their spaces and with others, and what matters most to them. Ethnographers spend time with people – in their homes and neighbourhoods, over meals, at community gatherings – meeting people wherever they feel most themselves.

However, the beginning of this project coincided with increased COVID-19 restrictions, leaving us to figure out: How can we do collaborative ethnographic research during a pandemic, when social interactions are forbidden and we’ve all been told not to leave our homes?

Because we had far less access to young people’s contexts – with communication and conversation relegated to the digital realm – we leaned into an an analysis of individual sense-making, blending phenomenology into our ethnography. Where ethnography relies on observation of interactions and behaviours, using objects and environments as windows into culture and focusing on the collective experiences of groups and segments, phenomenology captures first-person lived experiences, using words and text as a window into meaning making, and focusing on the individual.

Components

- Roles: In our ongoing effort to share power and work collaboratively with those with lived experience, we brought on two paid Youth Co-Researchers for this youth focused project, and had all youth participants edit their own stories.

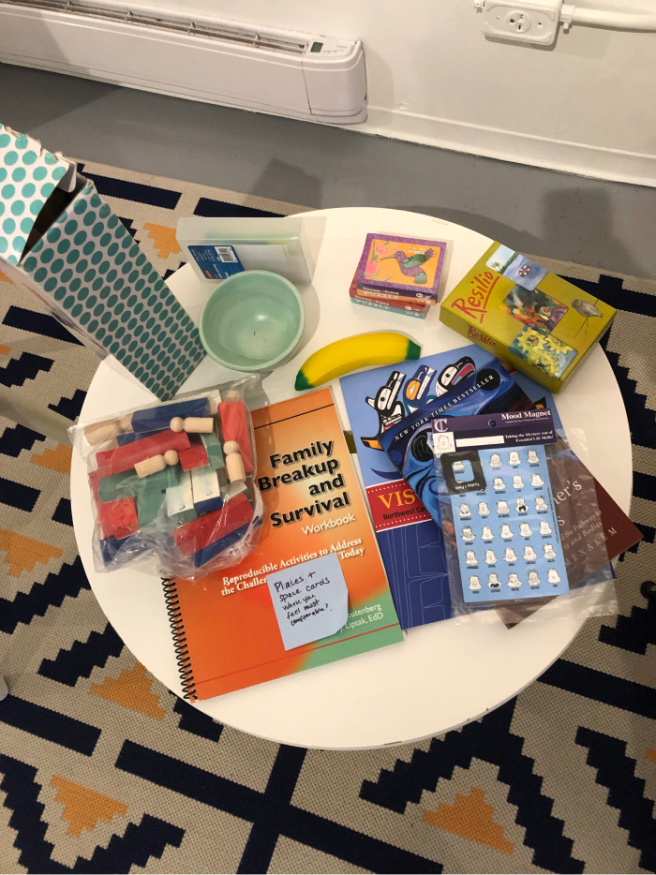

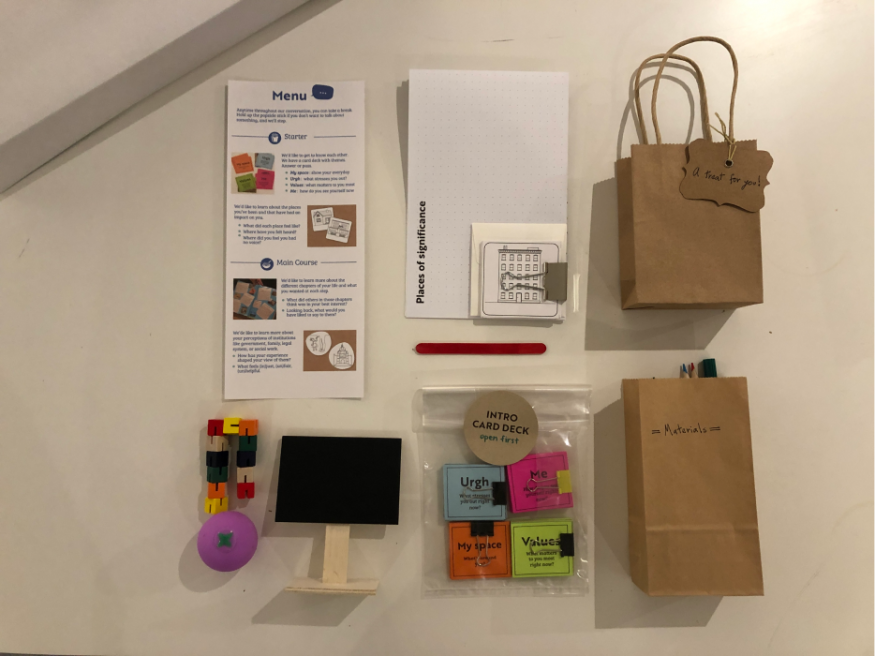

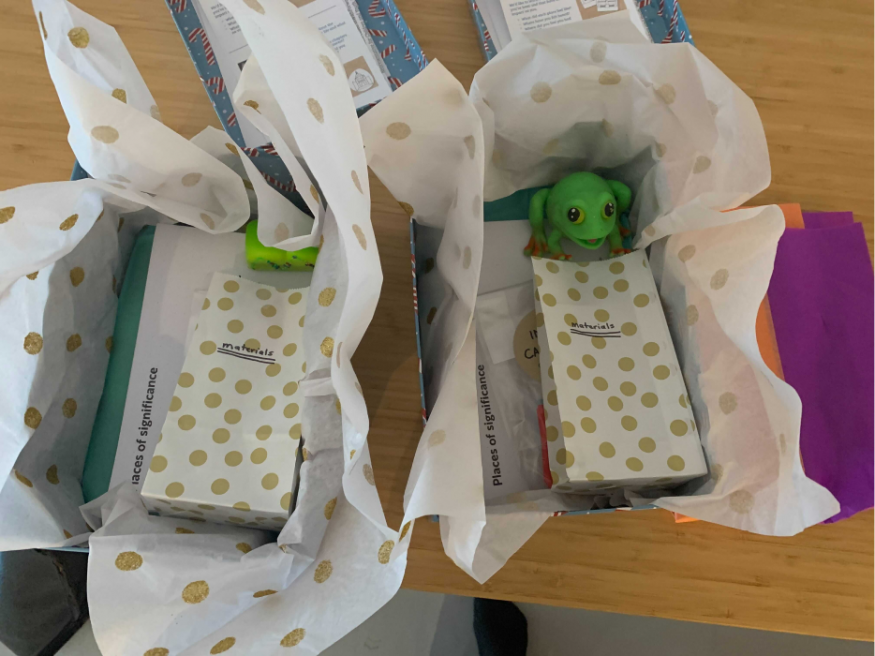

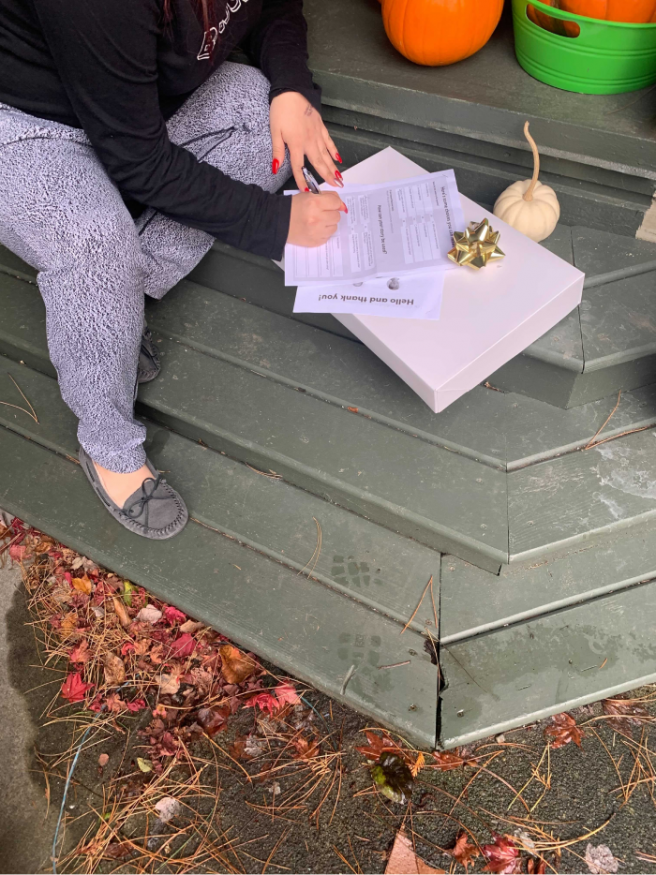

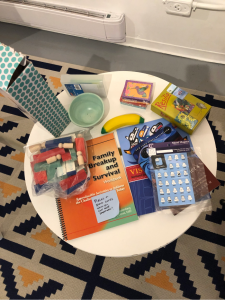

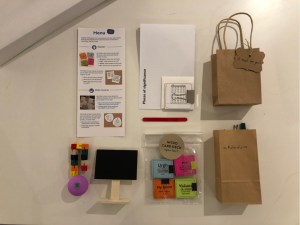

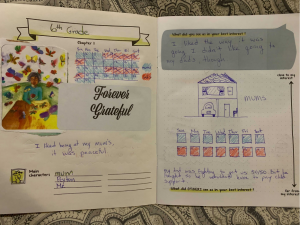

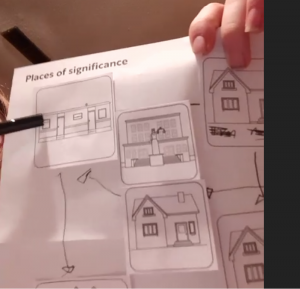

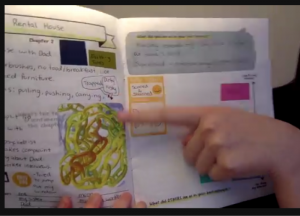

- Props: We mailed or hand-delivered an ethnography kit to each young person, full of conversational and projective prompts to facilitate connection – along with fiddle toys and plenty of treats!

- Settings: We spent time with youth over Zoom, connecting virtually from each of our respective homes.

- Scripts: We experimented with different value propositions and forms of communication including loads of text messages, and recruiting via social media ads.

- A set of principles: (1) Story collection is collaborative, not extractive. We move at the pace of young people – we work together – they have autonomy and control over how, and if, their story gets known. (2) Story collection is a closed feedback loop. We make every effort to return stories to young people for their review and to give renewed, informed consent. Youth can always reach out to us with questions, we show them what their stories and contributions look like, and where that information will go. (3) Story collection is an opportunity for catharsis and story editing. In returning stories to youth, we recognize this interaction as an opportunity to edit their stories, both literally and figuratively. We offer a safer space to share, to adapt, to vent, and to re-frame.

Roles

Youth as Co-Researchers:

In a continued effort to share power and make our research processes more collaborative, we hired two youth co-researchers to join our team. These youth helped to inform our outreach process and tool development, participated in interviews with other youth, supported in data analysis, and shared and edited their own stories to be included in this piece of work.

We benefitted hugely from having their perspectives on our team. However, because of time constraints (they are in high school) and the fluid – often urgent – nature of ethnography, we weren’t always able to include them as much as we’d like. Further, while ideally we would have co-written our final report together with our youth co-researchers, in actuality, we were the sole authors, upholding a typical hierarchical project structure in an effort to meet deadlines.

“…it doesn’t leave anything out…there isn’t really any faulty information there…It’s what I said. And I appreciate that you didn’t really change it up to try to play me as a victim at all…”

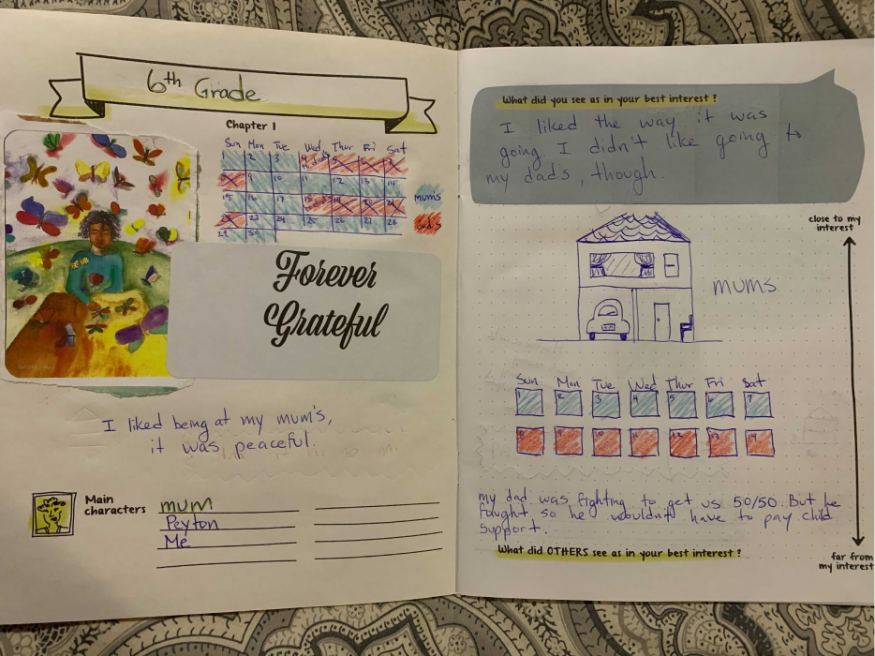

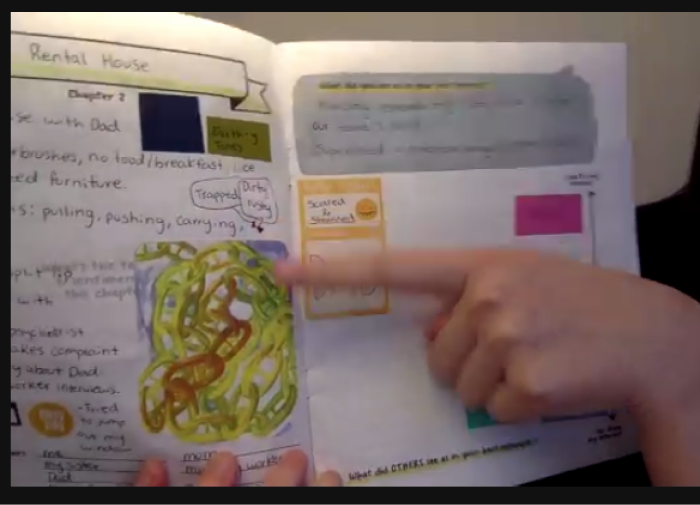

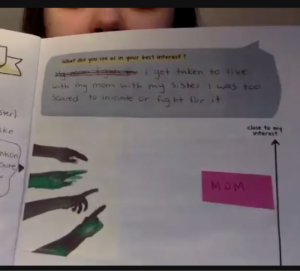

Youth as Story Editors:

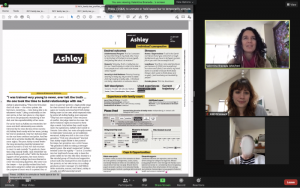

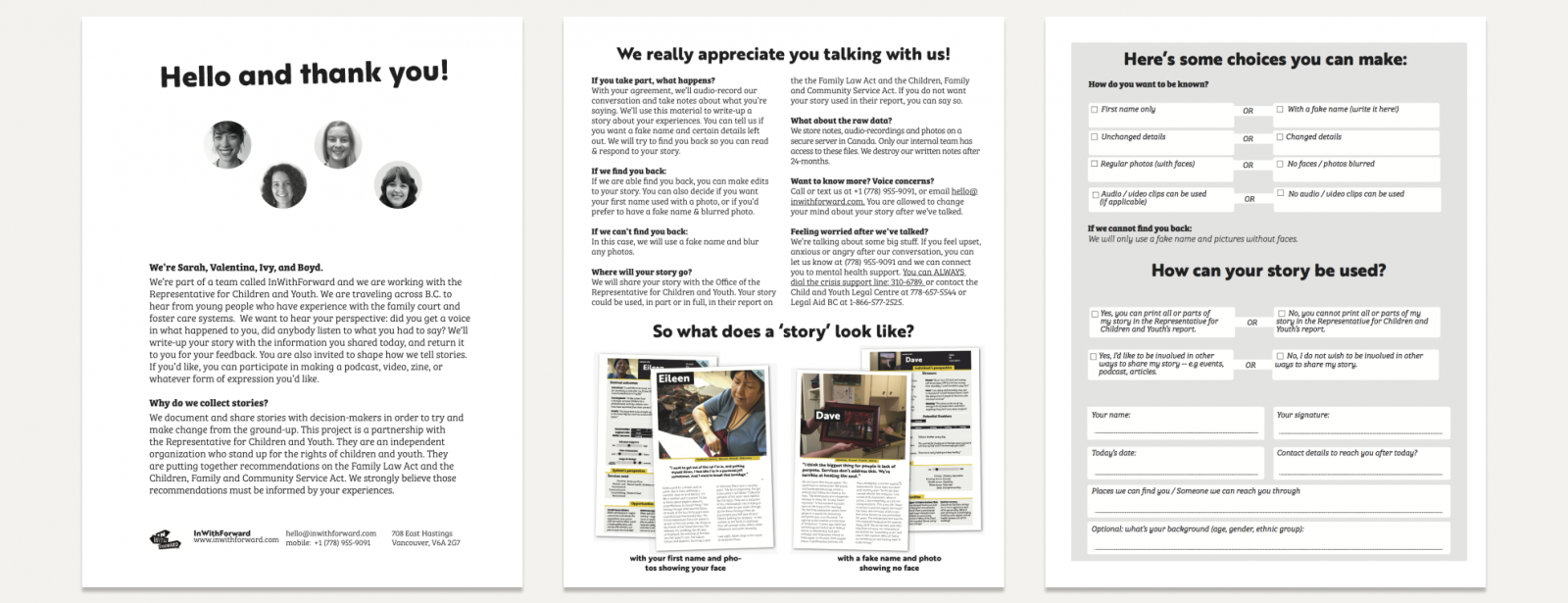

After putting together a first draft of their stories, we scheduled meetings with young people to give them an opportunity to review and edit the drafts. Sharing our screens, we went through line by line, making any changes youth suggested, verifying details, and adjusting any quantitative measures – like how much they felt heard, or how old they were when their parents first divorced- that we may have gotten wrong. We made it clear to youth: We are not the experts, you are. In these sessions, we also re-visited the consent form, giving them a chance to change the parameters of their consent, and to choose their own pseudonym. In this way, we close the feedback loop of story collection, allowing young people the power to review and edit themselves – serving as the ultimate authority on their own lived experience – aiming to cultivate a story collection and sharing process that is both collaborative and generative.

Props

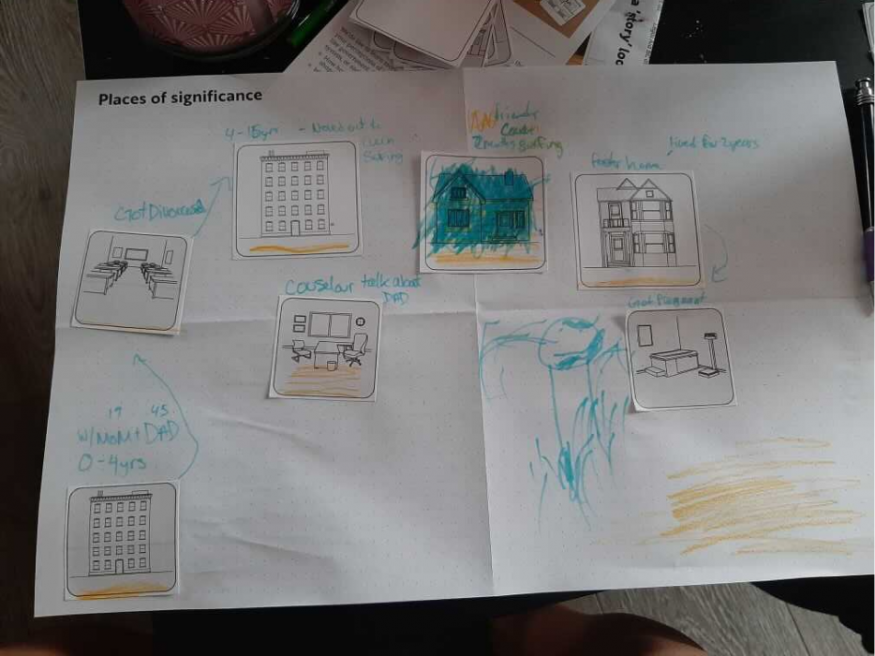

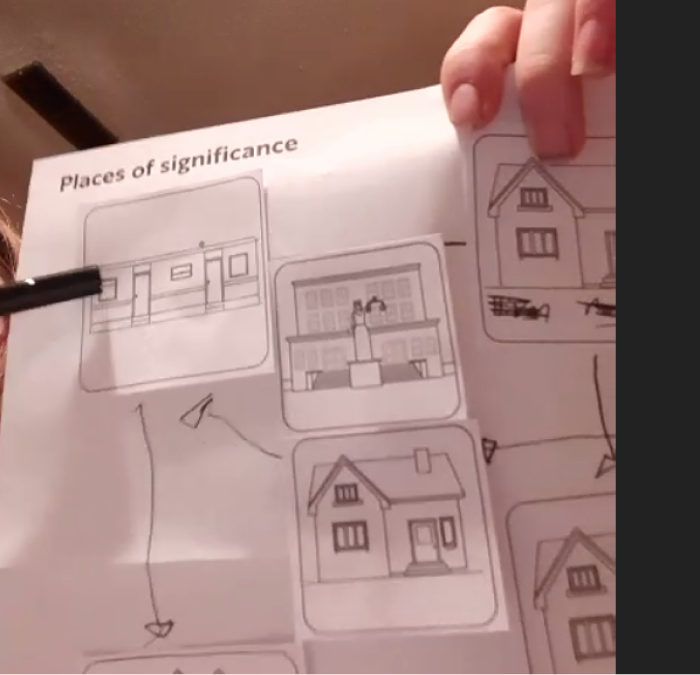

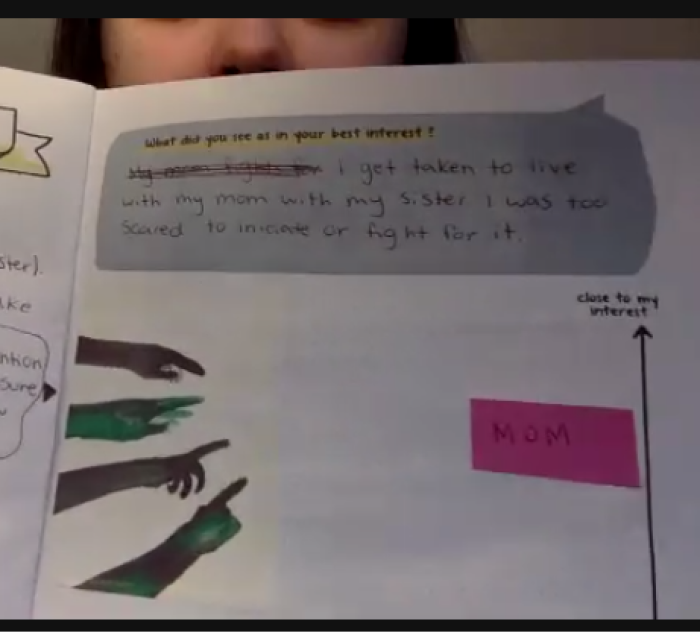

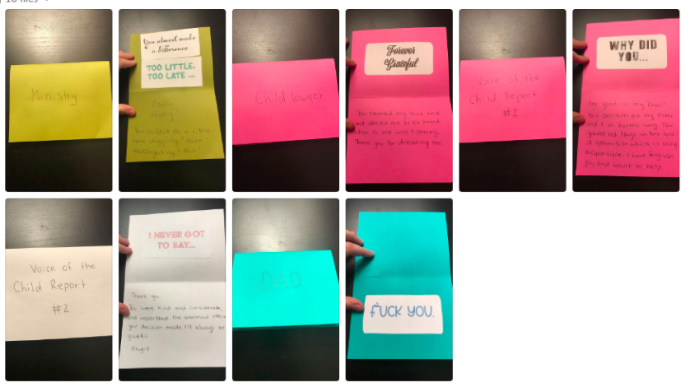

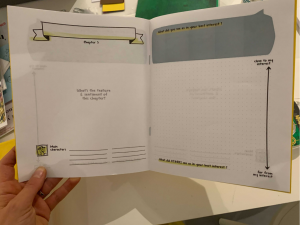

- Drawing on user-centred design methods, we created a set of provocations and prompts to guide our sessions with young people. Tools are not meant to be prescriptive, and unlike survey instruments, are inherently interpretative and iterative, meaning we add to them as we go, often discovering new words to express thoughts.

We use three types of tools:

-

- Conversation prompts help us to probe explicit needs and perceptions: what people value and find stressful, how they see themselves and their supports.

- Tactile prompts help us to get at people’s tacit experiences: the feelings and impressions that might be beneath the surface, for which people may not have a ready vocabulary.

- Projective prompts enable us to cast forward and see what people find attractive and desirable in the future.

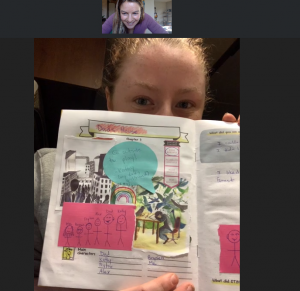

Because we could not meet in-person, we worked with our youth researchers to design tools that could easily be shared across a screen and through photographs, and sent youth all materials they’d need to complete any tasks. To help us gain a more holistic, ethnographic understanding of youth outside of a legal context, we added prompts and used gamification to share different things in our spaces (for example: an object that made us feel nostalgic, or happy, or frustrated). This also helped us to build a reciprocal relationship based on mutual sharing and vulnerability.

Scripts & Settings

While we did do some in-person recruitment, hitting the streets to knock on the doors of shelters and social service agencies, we weren’t able to connect directly with young people in this way, nor were we able to set up in-person meetings for story sharing and rapport building. Instead, both outreach and interviews had to take place online.

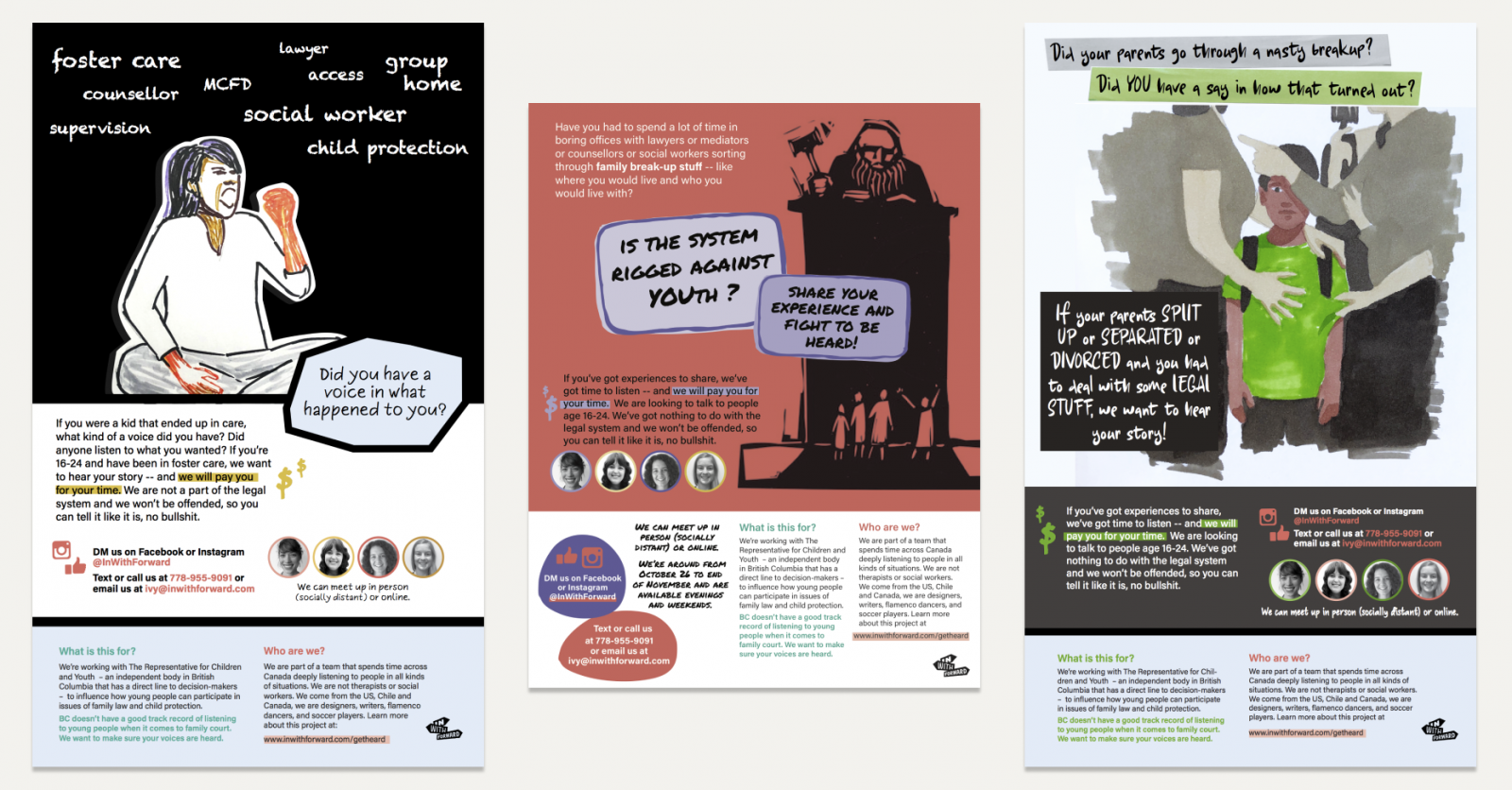

Posters and Posts: We experimented with different print and digital posters, trying some headlines that were more provocative – like “Is the System Rigged Against YOUth?” – and others that were more altruistic. We let youth know that they’d get to determine the scope of their participation as well as the extent to which their story is shared, that they will have multiple opportunities to give and re-give consent, and that we compensate them for their time with $50 per session.

We called service providers across the province, asking them to put up posters in their spaces, or to share them with youth via text. While many of these leads did not pan out, a few great conversations with youth workers did prove extremely fruitful. About half of our youth participants were recruited in this way.

Facebook and Instagram Ads: We adapted the content of our posters into Facebook and Instagram ads targeted at 16-24 year olds in various locations across BC including both urban and rural areas. Youth were able to reach out to us via a brief survey linked to the ads, and we followed up by text shortly thereafter. This strategy was super effective; within a day, we had over a dozen youth express interest in sharing their stories.

Zoom Interviews: While we did get to meet some youth briefly in-person (if we hand delivered their toolkit), all conversations took place over Zoom, with the majority of young people using a cellphone as their streaming device. Both this recruitment strategy and the means of engagement biased our sample towards those with regular wifi access and a usable device. Every session began with an explanation of the intent of the project in plain language, coupled with a read-through of the consent form, and an explanation of what to expect using our “Conversation Menu” as a guide. At this point, we always let youth know: they are in charge, they can share as much or as little as they like, and they can choose to take a break or stop at any point.

In typical ethnographic practice, we would go to youth, meeting them in spaces of their choosing – ideally, where they live – which helps us gain a better understanding of their particular context. While that approach is undoubtedly effective in allowing us to gather insights that help us to write narratives characterized by ‘thick description,’ it can also create a bit of imbalance in relationships between researcher and participant, making it feel as if the participant’s life is on display, while the researcher gets to remain relatively anonymous. An unexpected benefit of hosting conversations over Zoom was an opportunity to flatten that hierarchy, challenging the binary of the researcher vs. the researched. The tools we used required a two-way sense of vulnerability and sharing of personal spaces and items. In turn, we held up our cameras to our broken closet doors, our fruit fly infestations, and our favourite collections of knick knacks and photographs – creating a sense of mutuality and reciprocity by breaking down the fourth wall and bringing our full selves to the conversations.

Following each conversation, within 24 hours, we checked-in using their preferred method of communication (generally text messages) to open up a dialogue about any feelings that may have come up, or any need for further support, or connection to resources/services.

Zoom Story Returns: As part of our ethical considerations, we practice a double consent process in which we facilitate two formal opportunities for youth to give informed consent by signing a consent form, once in our initial conversations, and again when we share stories back with them. This way, they’re allowed to change their minds, they are consenting to the final content (which they’ve read and/or edited), and they know exactly what that consent means. At this point, they can choose to withdraw their stories completely without fault, to make changes to details, add or subtract photos (many youth chose to send us favourite photos from their own camera rolls) or make changes to level of anonymity. If we cannot find youth to return stories – most often in cases of housing insecurity – we default to anonymizing their profiles.

…I kind of feel happy about it. It’s so weird. It’s cool to see it…you have your own perspective, then to talk about your experience, and have someone else lay out your perspective, it’s like, ‘Wow, that’s totally it’…

Tensions

While we believe deeply in the power and impact of ethnography in influencing public policy decisions, doing ethnography within this sphere is tricky and raises a number of tensions. Where ethnography is fluid and borderless, legal parameters are inherently fixed; our partners were beholden to particular boundaries, not allowed to look at experiences that fell outside their jurisdiction.

For us, as ethnographers meeting young people, this was challenging. More often than not, youth didn’t know which legal mechanisms they’d encountered. Usually, they did not use legal language, nor have a strong sense of the legal proceedings that impacted them. Across the board, their experiences did not fit neatly within legal boxes. It was that messiness and nuance and dissonance that we found most insightful, presenting a compelling opportunity to recognize gaps between theory and practice, assumptions and lived experiences, and to highlight particular young people whose experiences may be overlooked.

However, our ability to delve into those insights was limited by the restrictions of our partner organization’s authority, often leading us to have difficult conversations about the role of ethnography and the kinds of data it is most effective at surfacing.

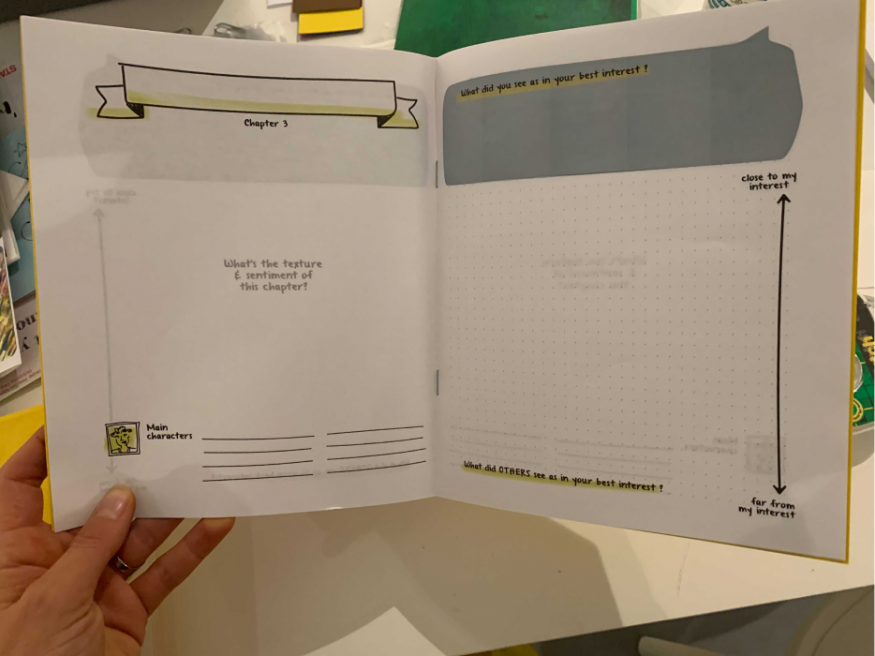

Analysis

In line with our blended approach of both ethnography and phenomenology, our analysis focused less on segmentation, and more on experiential themes. We designed our final report to feel evocative and representative of the stories we heard. Framing the analysis as a guidebook to bewildering legal landscapes, we highlighted themes that rose to the surface throughout our conversations and used metaphors to describe their contours – with chapter names like ‘Between a Rock and Hard Place,’ or ‘Nooks and Crannies’ – drawing attention to the main pain points encountered by youth navigating complex, confusing systems, and offering suggestions for future solutions in the form of “What if” statements.

Impact

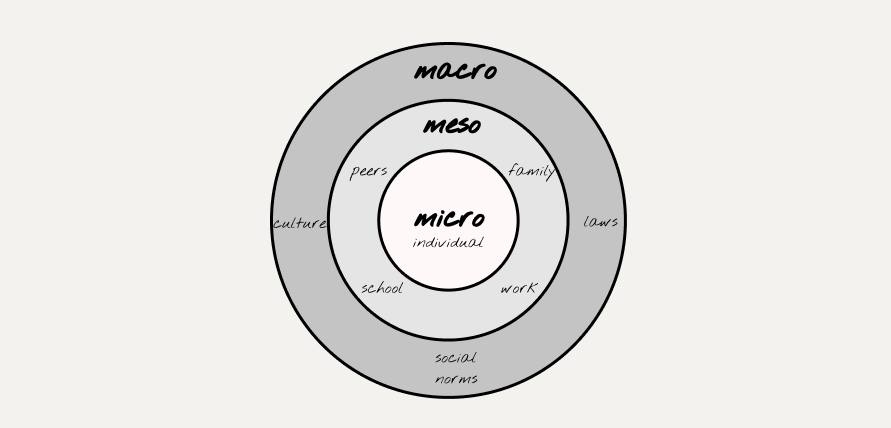

In looking at the impact of this project, it’s useful to employ Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory, which situates impact within different levels of one’s environment, beginning at the individual level and moving outward to one’s family and community, then even further to culture and systems such as laws and policies.

“… people have noticed that there’s been a change, I’m not so angry anymore…I was just like, keeping it in and like, just seething in rage and being like, ‘Oh, my God… I hate my mom. And ever since the talk… I’ve let things go.”

Micro Impacts

Our research team learned so much from youth, not only about the legal landscape, but about how to improve our communication strategies and research practices in a digital context.

Youth who shared their stories with us reflected that the experience was cathartic and that they were deeply excited by the possibility of helping other young people. It’s easy to assume that sharing will be uncomfortable or even painful, but youth told us the opposite: It felt good to finally be heard, and to know that they weren’t alone. At story returns, they told us they loved seeing their stories in print – and that having editing power helped them to feel confident and in control of the process.

Our youth co-researchers felt similarly. Not only was it empowering to share their own stories, but being a part of an ethnographic research team inspired them to do more of this work in the future, while hearing others’ stories helped them to feel connected to something bigger.

It’s really cool to see it all together looking so professional….this whole process has almost been therapeutic, to have it accurately depicted and to have someone really listen to me…to hear other stories and to know, I wasn’t alone.

“I have 3 words: hopeful, motivated, and grateful… grateful to have this conversation and really see where the work is going… I was really down in the dumps, but this has been a mood lifter…to see this work is actually being done…”

Meso Impacts

For many youth, this was the first opportunity they’d had to meet other young people with similar lived experiences. Until this project, one of our co-researchers had only ever met one other peer with divorced parents. Now, she’s been connected to and become a part of a family justice activist group. At the end of our project, we hosted a Zoom session for youth to meet each other, read each other’s stories, and to meet and ask questions of the Representative of Children and Youth (RCY).

Young people got to see the end results of their participation – a report – and to learn about next steps and processes for accountability, asking questions like, “How will outcomes be measured?” and “How do we make sure policy makers follow through on the recommendations from this research?” Upon meeting each other, youth reflected back gratitude for the “beautiful moments of sharing to make things better in the system,” for the “authentic connection,” and the feeling of kindredness one youth describes here as “invisible strings” of connection.

Macro Impacts

Ethnographic research deliverables like the ones from this project – a deck of stories and a report rich with thick data – changes the kinds of information that policy makers will read, therefore shifting their understanding of the problem space. Real quotes and stories that humanize the young people impacted by the pieces of legislature in question are more memorable, relatable and harder to ignore. It’s more difficult to view people as numbers when you know that they are also anime fans, poets, drummers, fashionistas, and Jedi masters.

This type of engagement and relational research has also created an opportunity for youth to get more involved with RCY through speaking opportunities and advocacy groups.

Team and Partners

This project was lead by Ivy Staker, Valentina Branada, and Sarah Schulman of the InWithForward Team, with critical support from our youth co-researchers, Lauren Irvine and Maya LeBrun, in partnership with the BC Office of the Representative of Children and Youth.