All around the globe, countries and cities want to know if people are happy and well. They try to quantify happiness and wellbeing using standardized scales (like how satisfied are you on a scale of 1-10) or generic indicators (like access to parks or primary care doctors). Only the generic indicators don’t tell us how happy or well people feel, and the standardized scales hold different meanings to different people based on their own lived experiences — or whether they’ve had their coffee yet.

Context

How do cities currently measure wellbeing?

For too long, Canada (and pretty much every country) has valued the economy over all else. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has been the gold standard in measuring what matters. GDP tells us about the state of our sales, but not about the state of our souls.

How do we understand the state of our souls? And is wellbeing even a state? Or is it a series of moments, or a dynamic process, or …? We don’t have the answers, but we do know that wellbeing cannot be reduced to just one thing, nor is it something that happens to us: it’s something we feel inside of us.

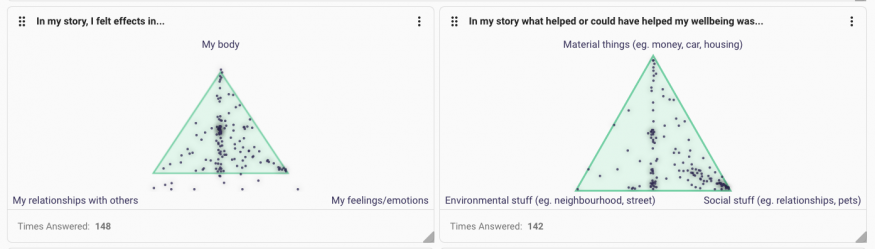

Drawing on the perspectives of 59 street-involved Edmontonians whose stories we’d collected over the past three years, we co-developed a wellbeing framework. The wellbeing framework is not meant to be prescriptive, but rather descriptive, to help us talk about the parts of wellbeing, and what that looks and feels like for each of us. We believe that wellbeing is about more than the absence of illness or the presence of material things, ancient, intuitive and local wisdom tells us. Wellbeing is personal, rooted in the different connections we feel: to ourselves and our bodies, to the land, to family and community, to the sacred, to culture, and to the human project of finding purpose and self-actualization.

That means we can’t just boil wellbeing down to a number. And we think the ways in which we measure wellbeing need to themselves enable wellbeing. As in, they shouldn’t feel exploitative, frustrating, or meaningless. It shouldn’t feel like you’re having to contort your own perspective to fit with someone else’s categories and assumptions.

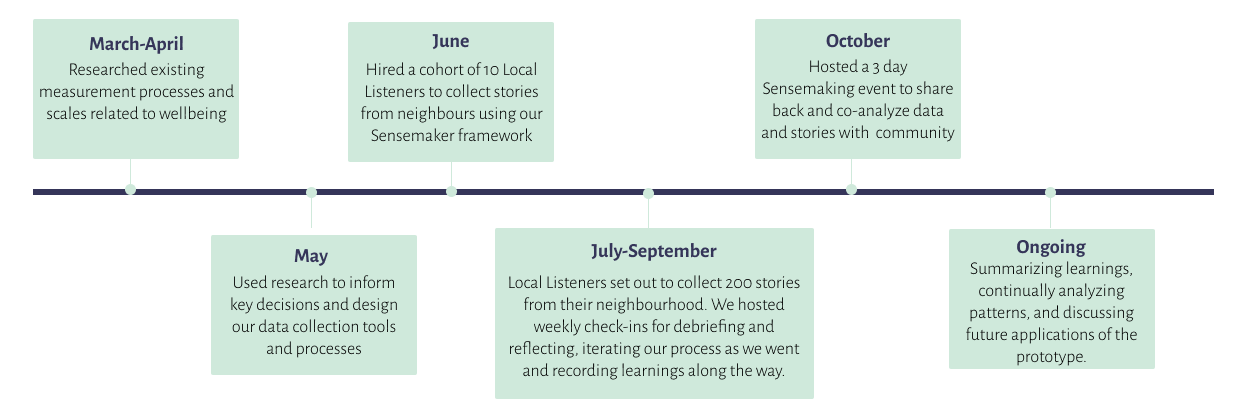

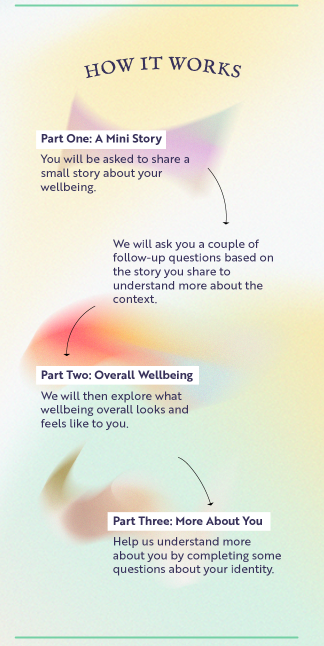

With that in mind, we teamed up with the City of Edmonton’s RECOVER team to test a new form of listening infrastructure in, with, and for communities. We wanted to learn how to shift data from being a numbers-driven exercise, based on colonial ways of knowing, towards data as a storytelling experience, nourished by multiple ways of knowing and being. We called it: Auricle.

Read more about the prototype, how it works, and what we stand for at auricle.info.

Components

What did we test?

- Values: To try to live into our anti-oppressive and de-colonial values, we needed to explicitly reject data gathering as an extractive activity, and instead develop language & practices that honour mutual respect, relationality, experience, and context.

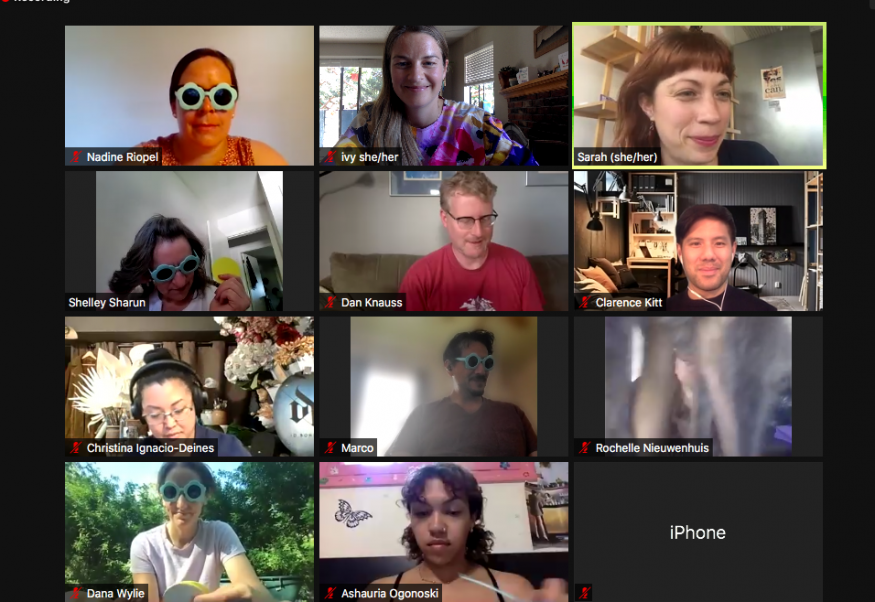

- Roles: In an effort to create an experience of data collection rooted in reciprocity and relationship, we hired 10 Local Listeners to meet, connect with, and gather stories from their neighbours.

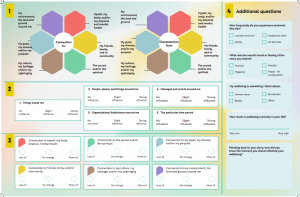

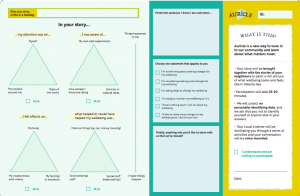

- Data Collection Tools: Eschewing dominant, colonial methods of surveys and focus groups, we blended the qualitative and the quantitative using a narrative-based data collection platform called Sensemaker.

- Community Sensemaking: Our intention was to involve neighbours in the process of sensemaking and analysis at every level, from the moment they shared their own story, to a festival in which they were asked to engage with and react to raw data and stories contributed by their community, to a digital dashboard that they can use to seek out patterns and insights on their own.

Roles

What if, instead of city staff with clipboards stationed at street corners asking folks to fill out surveys, we asked locals with lemonade, or pet kittens, or clown outfits to engage deeply with their neighbours, to tap into their networks to connect and collect stories of wellbeing. Would shifting the data collection interaction lead to richer, more nuanced understandings of wellbeing? What might we learn about what makes people feel well? Could this interaction in and of itself contribute to wellbeing for both those gathering and sharing stories? We set out to find out by creating a new role, the Local Listener, hiring 10 neighbours from Alberta Ave keenly interested in learning about what wellbeing means to those in their community and committed to seeking out voices that often go unheard. We intentionally sought out and selected candidates with links to underrepresented communities and a real desire to foster deeper connections in their neighbourhood. Read the job posting here.

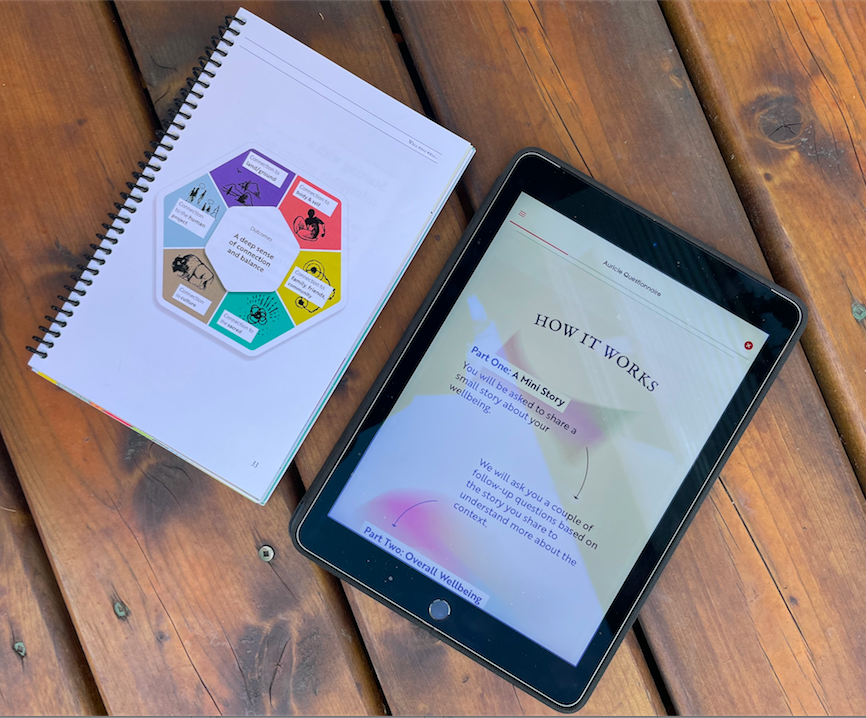

After a thoughtfully designed interview process, we brought together an inaugural cohort of ten Local Listeners for two weeks of onboarding session during which time they each received a physical welcome package, including a handbook with lessons and exercises to ground them in the theory, values, ethical framework and philosophical underpinnings of the prototype. Click here to read the Auricle Handbook.

Traditional Approach

Staff members distribute surveys or host focus groups, or hire contractors to survey residents in public places, simply asking a series of pre-scripted questions and then moving on. Hard-to-reach groups are left out, outreach is minimal.

Our Key Decisions and Theoretical Shift

We hired neighbours to engage deeply with other neighbours in a relational and values-based way, intentionally seeking out marginalized perspectives and those who otherwise may not be heard.

Rather than transactional, these interactions were intended to be relational and values-based, contributing to a sense of connection and wellbeing, not just a means to an end.

What did we learn?

- Philosophers fare well: The Local Listener role, as it was designed, was best suited for folks interested in deeper philosophical conversations and explorations of wellbeing. Those who were more task-oriented and less interested in further inquiry struggled with the extra intellectual and emotional demands of a role that ran much deeper than simply collecting data and ultimately decided not to continue their participation. This raises questions around potential challenges in implementing Auricle in more traditional settings in which folks may struggle to reimagine the established boundaries of a “research” relationship, a reframing that has proven to be unsettling for some.

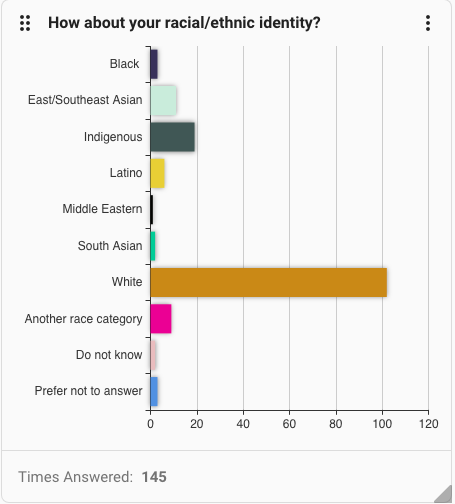

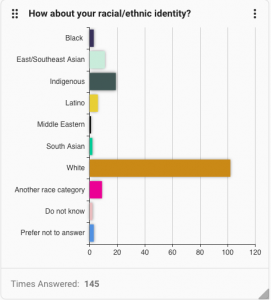

- Diverse listeners = diverse storytellers: While Local Listeners did an excellent job of tapping into their personal networks and seeking out new perspectives, there were still significant gaps in who was able to contribute a story, particularly amongst newcomers. In the future, this can be explored by expanding the cultural and racial identities of our Local Listeners and hiring more newcomers.

- Relational work is worth it: Hiring Local Listeners does, indeed, make a difference in the quality and depth of interactions. Both Local Listeners and story sharers expressed a deep sense of connection to their community through the act of sharing, listening and reflecting. As one Local Listener, Mary, explained:

“This reminds me of a story from up North, where there were very high youth suicide rates. And a grandmother took it upon herself to go out, and check-on young people every morning. And those suicide rates came down, and I think it’s because of her role. These positions like the local listener, where we are just talking to people, asking them questions that they probably have not been asked before, and opening up dialogue, can really impact things. They start to know me now. And I know more about them. Just those little things we now share will make an impact. And, personally, these are things I don’t normally ask myself. So it’s giving me some introspection into my own life: how do I know if I’m well or not? It’s been a great learning, with great insights, that I see impacting our community in some positive ways.”

Tools

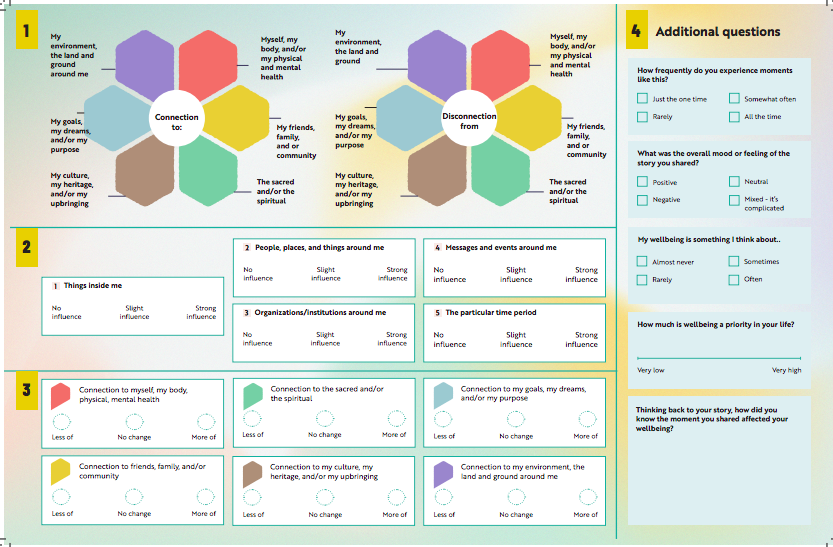

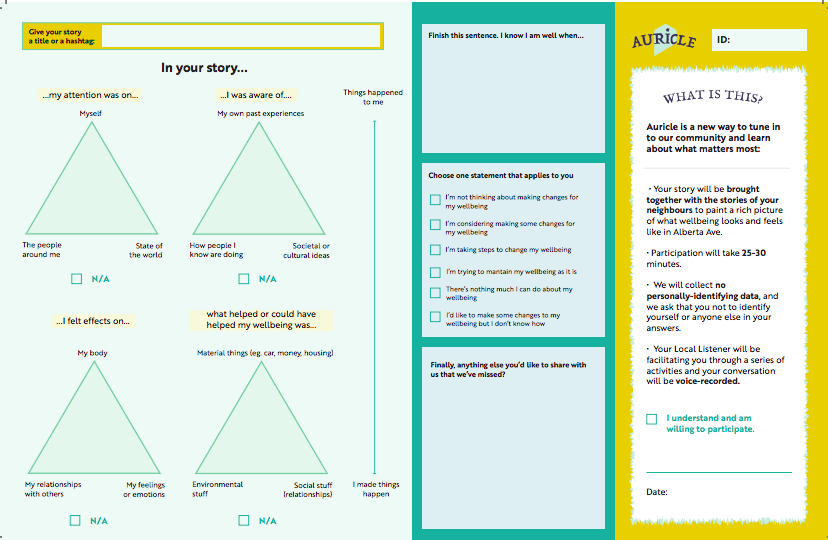

What if, instead of 7-point-scales, generic online survey monkeys and a set of predetermined indicators, we could gather richly qualitative data without losing the substantive analytic power of quantitative measures. Could we take a “qualiquant” approach? Enter Sensemaker. Rooted in Dave Snowden’s Cynefin framework of complexity, Sensemaker is a data collection tool that uses micronarrative prompts and a series of follow-up questions to explore complex issues and sentiments, decrease researcher bias, and allow story-sharers to self-signify the meaning of their own data.

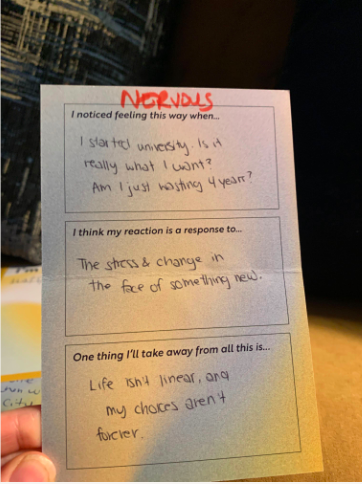

What is a micro-narrative or micro-story? A micro-narrative is a short, largely undigested snippet of a story. The kind of brief chatter you might hear at the bus stop or the playground, standing in line at the grocery store or shelter, or as you and your colleagues wait for a meeting to begin. It’s a brief moment in time shared in one’s own words.

“We need to understand what’s going on, and you can only understand a complex system by understanding the small particular parts of day-to-day interaction. For humans those are the anecdotal data of the school gate, the street stories, the beer after work; not the grand narratives of workshops but the day-to-day anecdotes of people’s existence.

And we need to understand them through the voice of the people who tell them not through an AI machine interpreting the text or an expert making them fit their cultural expectations.

The people’s own voice has to be subject to their own interpretation.

And then we need to allow those in power at any level of society to have direct access to the raw stories of the people they govern, without multiple levels of interpretation which allow them to hide from reality behind the guise of policy reports.”

– Dave Snowden, Founder of Sensemaker, listen to his full speech here.

Traditional Approach:

Quantitative surveys with multiple choice questions and likertscales that attempt to assess objective wellbeing based on a predetermined set of indicators

Our Key Decisions and Theoretical Shift

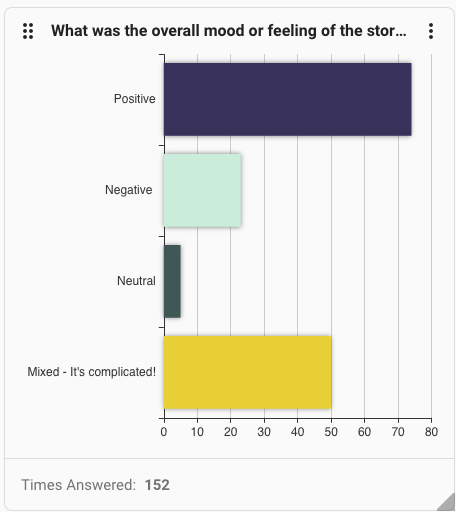

We used a tool called Sensemaker (Based on the Cynefin framework of complexity) that offers a “qualiqaunt” approach. Rooted in narrative, the tool allows folks to share a short story in response to a prompt, then allows them to signify the meaning of their story in a series of follow-up questions. This method allows neighbors to contribute to analysis at the point of sharing, rather than having their stories interpreted by outside “experts.”

Working towards co-production, community ownership and reducing researcher bias by allowing self-signification, and moving away from trying to validate or prove a hypothesis, instead building in space for learnings to be emergent.

What we learned:

-

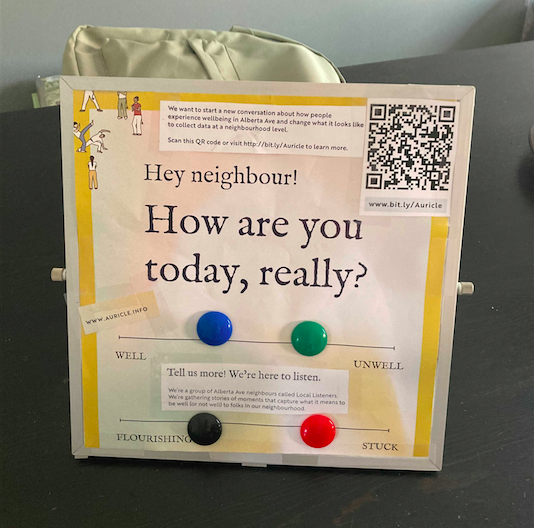

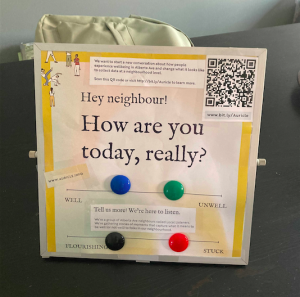

- There’s no such thing as a one-size-fits-all interface. Each Local Listener set out equipped with a tablet and the Sensemaker App, yet, technical issues like crashing and freezing, combined with a sense that using a tablet as an intermediary in the conversations felt unnatural and stilted, led us to quickly iterate, producing a paper version of the story collector that was much better received by both Listeners and Sharers. Sometimes, even the slickest interface can stand in the way of an organic, authentic interaction.

- Understand your data output while designing your data input. Hindsight really is 20/20. After completing the design of our data collection framework and ending the data collection period, we quickly realized that more intentionality around how data would look on the backend upon designing the front end was necessary. Certain questions could have been restructured in order to produce data points that were far easier to share back and to analyze saving us both time and headaches.

To see how data looks once collected, explore our Public Dashboard.

Sensemaking

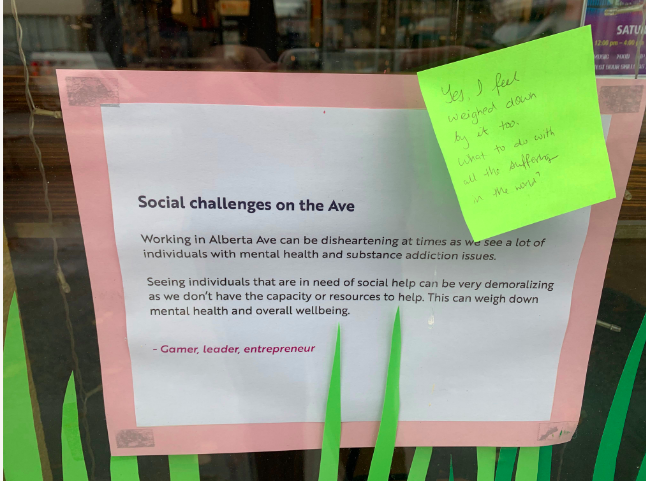

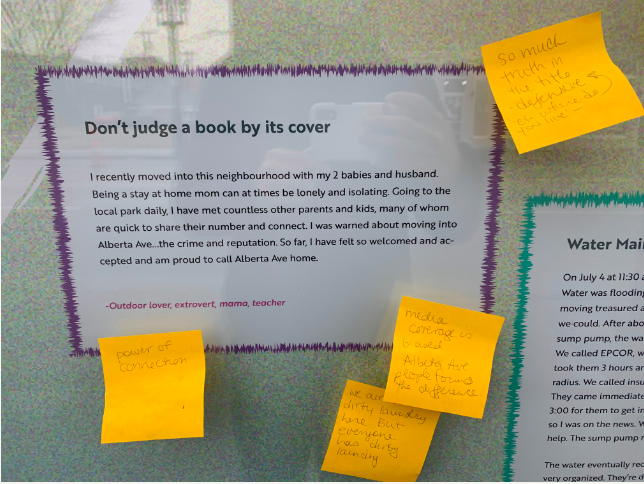

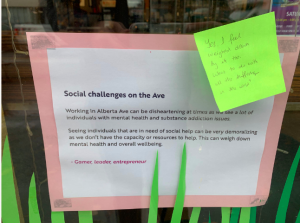

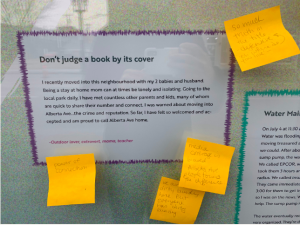

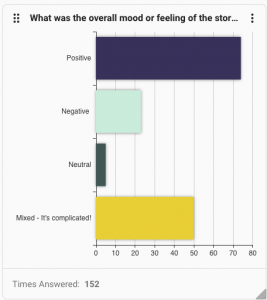

What if, instead of our team sequestering ourselves in a room to analyze the stories and data collected, we invited the community to join us in making sense of what they and their neighbours had shared? That was the idea behind Knowsy Fest, a three day celebration of stories on Alberta Avenue during which stories were displayed on storefronts and visitors were asked to reflect on and respond to the content. What emotions did the stories bring up for them? What patterns or insights did they notice? Participants were invited to respond in a variety of ways, including through mind maps and reaction cards, and were invited to delve deeper into the data by exploring our public dashboard.

Visitors to Knowsy Fest were given magnifying glasses and invited inside as “co-analyzers” to explore one of three different story packs, curated based on specific criteria such as whether or not they prioritize wellbeing, whether or not they felt they had made things in their story happen (or those things had happened to them), and if they identified as Indigenous.

Click here to read Story Pack 1: Priorities.

Click here to read Story Pack 2: Agency

Click here to read Story Pack 3: Indigenous Stories

Traditional Approach

A select team of “experts” spends time analyzing the quantitative data to pull out patterns, statistics, charts and the like. Conversations about the data in its rawest form are relegated to small, internal teams and data is only presented to the public post-analysis.

Our key decisions and theoretical shift

Returning data to the community in its most basic form. Neighbours were asked for their insights, invited to help us make sense of what was shared and to play a role in shaping the narrative of the data, as well as where the data will go moving forward. We used prompts to start intentional discussions, gauge reactions, and identify patterns.

Again, a focus on emergent, rather than evaluative research, shedding the “expert” veil and bringing community into analysis processes, placing value on people’s reactions and reflections in response to stories and data, and using statistically insignificant, yet intriguing, patterns as “clues” for further questioning and exploration

What we learned

- Take it to the streets. Although originally necessitated by COVID-19 restrictions, sharing data back with community in an outdoor venue turned out to be a fruitful and strategic approach, very much in line with out values of community ownership and collective sensemaking. The fact that stories and data were accessible to all along the streetscape – not behind closed doors – with volunteers present to invite feedback and reactions, increased public visibility and expanded engagement far beyond what would be possible with only an indoor venue.

- People are ready to engage again. A long and tumultuous period of pandemic-life has left many of use with the sense that folks are shying away from connection, but our Knowsy Fest left us feeling much the opposite. We witnessed a healthy appetite for engagement and a true curiousity from neighbours to learn more about how their fellow community members have fared

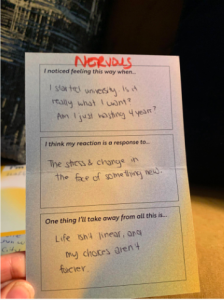

- Offer space to share and reflect. As part of the Knowsy Fest materials, we included reaction postcards which invited visitors to mull over and share some thoughts about their own wellbeing and what bearing witness to these stories had brought up for them. Upon reading through these, our team was surprised by the rawness and vulnerability of these reflections about individuals’ own wellness, which tended to express negative feelings of being unwell, unworthy, or lost, leading us to believe that more space needs to be created for folks like these to share and be listened to, and that having access to real stories from neighbours can help to open up that space.

What's Ahead

Auricle as a prototype proved itself worthy of further exploration and application. Discussions about its future are ongoing as we continue to summarize our learnings and ponder where this story-based approach to data collection and understanding wellbeing might be most impactful. If you are interested in learning more, or keen to bring Auricle into your sphere, don’t hesitate to reach out to us at [email protected].

Partners

Auricle is a collaborative prototype between InWithForward and the team at the City of Edmonton’s RECOVER urban wellbeing initiative.