Categories

The InWithForward (IWF) team had a history of successful and failed partnerships and a growing list of conditions, indicators, and question marks about the difference between them. Over the course of IWF and RECOVER’s relationship, we’ve turned some of that je ne sais quoi into principles, practices, and rituals that help us bring about what’s needed to do transformational work.

Here we share some of the themes, insights, and illuminating moments that have helped us shift from looking for the perfect partner to eking out and cultivating a relationship purpose built for what we both want to be and achieve in the world.

#1: Curiosity gives the cat a tenth life

Our partnership is inquiry-led, which means we work on the assumption that we do not already have the solution to urban wellbeing, and that there is not one solution to urban wellbeing. Instead, through a process of inquiry, we can get to better, and more nuanced, questions. Along the way we amass a lot of learning and insight that drives more learning, as we find ways to close the gap between what we know to be true, and what we are actualizing in the world. That gap is something to be curious about.

The gap between what is and what we value & know to be true is an uncomfortable one, right? Long after I’ve accepted that it’s not helpful, and even harmful, to yell at or criticize my kids, I find that I continue to yell at and criticize my kids in moments of reactiveness. It makes me feel bad and ashamed. Nonetheless, my work teaches me that we can get curious about that gap, if we accept that:

- Part of being human is that there will always be a gap between what we know/value and how we behave;

- We can spend our whole lifetimes working away to narrow the gap; and,

- That every millimeter by which we narrow these various gaps in our lives can be profoundly meaningful

Curiosity is a great antidote to shame, judgement, futility, and tunnel vision. We’ve tried to cultivate curiosity within our own partnership, and to seek out Edmontonians to collaborate with based on some shared questions we hold.

Here are some of the questions that have kept us curious this year, and helped us find out-of-this-world (but entirely Edmontonian) people to work with:

- How can regular Edmontonians better show up for fellow Edmontonians struggling with different kinds of grief and loss?

- How can we support Edmontonians to connect meaningfully with each other across differences?

- How do different kinds of Edmontonians think about and recognize wellbeing in their own lives?

- How can we begin to measure and share learning about wellbeing, as experienced by particular neighbourhoods, rather than using generic indicators that make a lot of questionable assumptions about what matters?

- Can the act of asking about people’s wellbeing, and truly listening, increase wellbeing? Under what conditions?

Moments where curiosity made the difference

Resisting our inclination of jumping to solutions

“Within our municipal government context, it is expected that public servants will do everything they can to try to solve problems that people in Edmonton are experiencing with the services we provide. (Admittedly, that is not how many people experience a relationship with the City, but the expectation is there.) In our quest to solve problems, public servants (us included) often jump to solutions. But in doing this, we risk creating bigger problems. In jumping to solutions, we don’t give enough time to explore what the actual problem is. Back in 2017 when RECOVER was first established by City Council, Council told us to go and figure out how to build a “one stop shop” where multiple social services could be housed under one roof. At the time, it was thought that a better coordination of services would solve the challenges faced by several neighborhoods in and around the downtown core.

But before our team went off and started planning for a wellness centre, we got curious about a key question: “is that what people actually want?” And the people we were curious about, were not just the service providers or the neighbours in the neighbourhoods who were housed, but centrally and importantly, we were curious about if those who it was imagined would use the ‘wellness centre’ thought it was a good idea.

It turned out that they didn’t. It turned out that what they told us about what it meant to live a good life didn’t involve a focus on the material aspects of wellbeing, but rather that living a good life meant refocusing on the immaterial aspects of wellbeing.

Our initial curiosity opened up the space for the wellbeing framework to emerge, and — we hope — a real chance of improving the conditions for wellbeing for everyone in our city, in particular for those who have experienced life at the margins as a result of dominant structures and systems.”

— Miki Stricker-Talbot

Hiring every day folks to learn alongside

“In early 2021, we created and hired for a new role, the Losstender, and by late spring we were trying to hire another team, this time of Local Listeners. We advertised for passionate Edmontonians, irrespective of education or work history, and we extended an opportunity to learn with us.

For the Losstender, the job ad read: “We offer training, a culture that’s big into learning from the tough side of life, debriefing, reflection, and the opportunity to find the ‘so what?’ of painful experiences.” We received over three times as many applications as expected. And we’re not talking generic resumés, we’re talking about letters and videos where people talked about their sense of purpose in life.

In our callout for Local Listeners we asked: “What would it look like for a city to engage citizens in more humble and authentic ways, deeply listening and understanding what wellbeing means to them?” The team that resulted courageously tried so many approaches to outreach and rapport-building. They voluntarily posted pages of reflections on our Slack channel about what they were learning and experiencing through interactions with neighbours. Throughout both prototypes, we made the experience of uncertainty a focus of our regular debriefs, rather than trying to resolve it. And through it all, we celebrated what we were learning about the questions we shared. For so many Losstenders and Local Listeners, the opportunity to learn in community seemed like so much more than a job.”

— Natalie Napier

#2 - Reconceptualizing power & roles, on the daily

One kind of expertise that IWF brings to the partnership with RECOVER is around working with people who don’t tend to participate in civic processes. Part of IWF’s mission is about reconceptualising how power works in the social welfare state; that is, thinking about how government and its delegates can better nourish the agency and autonomy of even the most marginalized citizens. And, the team at RECOVER, steeped in a municipal institution, recognized that we can’t reconceptualize power in community without inspecting our work relationships and structures. Together, we’ve turned this lens on our own teams and partnership.

- Power doesn’t have to be a zero sum game

- Structure should create the conditions for acting with discernment and integrity

- COVID offered some good lessons in giving up control

- The practices that help us reconceptualize power are time consuming

Things we’re learning about power

Power doesn’t have to be a zero sum game

Shared power doesn’t mean everyone has the same amount of authority in every context. It’s more like creating the conditions for people to unwrap and deploy their gifts towards shared goals.

Structure should create the conditions for acting with discernment and integrity …

rather than seeking to tightly control behaviour. We’re going for somewhere between the rigid roles and routines of traditional workplaces, and an ‘everything goes’ approach which leaves people feeling unsupported and uncared for. Especially in the uncertain spaces of systems change work, we need some scaffolding to orient people to the ‘why’ and the ‘how’ of the work, and we create rituals through which people can build trust, feel heard, dream, reflect, and take stock of learning. It allows us to stay grounded in a bigger relational picture of accountability, and more clearly defines “the sandbox” we’re in.

COVID offered some good lessons in giving up control

As public servants and social designers, we’re accustomed to being judged based on our performance. But a preoccupation with performance can keep us from taking chances, and being vulnerable enough to learn. Often we associate performing well with being in control. When the global pandemic had us all holed up in our homes on Zoom, we had to share differently in the work, and invite in people we’d never met in person to carry out work on the ground. We learned that what we could have more control over was creating the conditions for trust, and a culture of curiosity, learning, and experimentation. And then we had to lean into that trust and relationshipping.

The practices that help us reconceptualize power are time consuming

Modern, Western, colonial culture doesn’t have a lot of patience for the long check-in, the layers of introductions, the scene-setting rituals, and land acknowledgements that actually make space for deeper learning about our responsibilities to each other and the land. Making time and space for these practices takes tenacity and bravery. Sometimes we default to our old ways, and have to remind ourselves not to skip steps. Really, we’ll be learning this forever, so settle in.

A realization with gratitude

While organizing Knowsy Fest, a fall 2021 event where we returned and made sense of local stories of wellbeing, we forgot to think about our partnership as part of an ongoing prototype. We were so focused on creating an interaction for different kinds of neighbours in Alberta Avenue, that we forgot to apply intentionality to our relationship with each other. IWF inadvertently stepped back into consultant mode. RECOVER yearned to do more co-production, but settled for helping with discrete tasks. Eventually, when we got on the ground together, our mutual investment shone. It over-rode all our fears about individual performance, or traditional roles.

Members across our teams took initiative, filled in gaps, pulled long hours, broached reflective conversations about process, pitched in, bringing lamps, fire tables, patio rugs, etc. from their homes to bring our spaces alive. In hindsight, we could imagine how we might have designed the event as a total co-production from the start. We realized that we were ready to work as a fully integrated team with a great collection of complementary skill sets: our partnership was evolving.

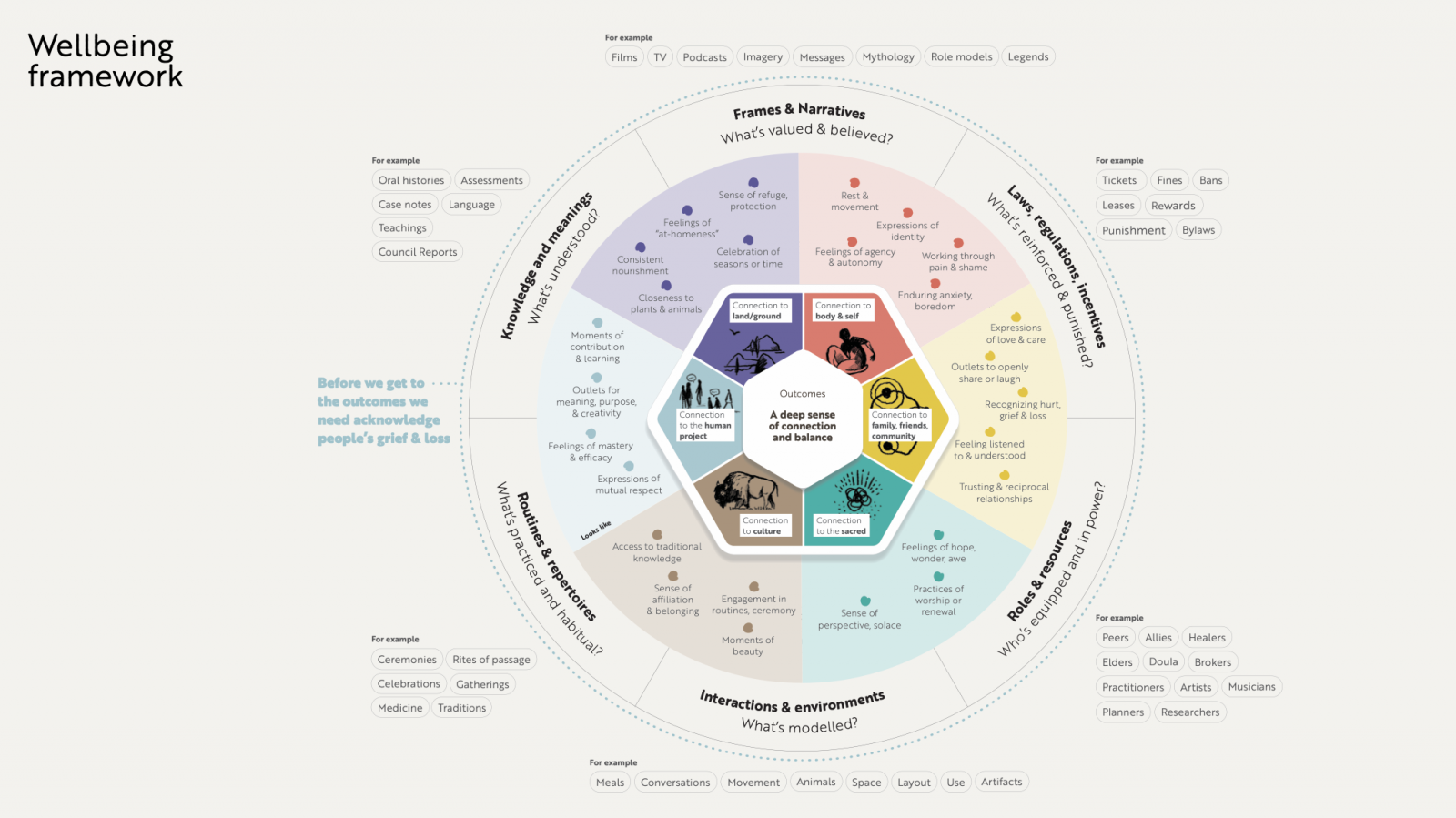

#3 - A shared framework helps us live into a shared vision

In the winter before the pandemic hit, we combed over all our ethnographic data from folks living rough and precariously in Edmonton. We looked at what Indigenous, Western, and Eastern traditions had to say about what makes for a good life, and we asked ourselves, ‘what does all this tell us about wellbeing?’ Spoiler alert: it told us that while we have recently come to be quite focused on material wellbeing in the Western world, and beyond, that intangible experiences of connection are what we are all really after. Food, shelter, clothing, and other concrete resources are just a means to a more connected life.

We think to a lot of people it makes intuitive sense. On the face of it, the wellbeing framework feels uncomplicated. It’s in the application to our lives and systems that it gains infinite nuance. Having a shared framework has enabled us to find words for things some of us rarely referred to in the past, to access meanings that felt just beyond our grasp before. Some of us were more at home with our state of connectedness to begin with, and for others of us (myself included) it has transformed how I relate and what I know to say and do in both professional and personal spaces.

It’s one thing to grasp this intellectually. Personally, I find that the satisfaction that I get from understanding something on an intellectual level often comes quickly, and sometimes satisfies me just enough that I fail to go deeper. I find the systems and environments in which I operate rarely (if ever) require me to go any deeper. The wellbeing framework has challenged me to think about other ways of knowing and what we give our attention to in the spaces we’re in.

RECOVER team check-in ritual

“I tend to lead from my heart. I find I am able to better sense things when I approach them with EQ (emotional intelligence) and LQ (love intelligence). When our team first took up the framework, I noticed that I felt frustration by the way our team was intellectualizing the experience of connection. After all — isn’t connection something to be felt in the heart? In the eyes? In our spirits? In response to that feeling, I introduced a new team practice: a check-in ritual that subtly built on the framework as a way to get people to attend to our relational states.

On its face, the check-in ritual is quite simple: I pose a question rooted in the notion of connection, and people respond from their own personal experience and attention paid to their own social locations. But within a professional municipal government context, these types of questions usually don’t get answered… never mind asked. The check-in ritual provided space for us to show up as we are and as we were — in our full human-ness and humaneness.

Over the time of the pandemic, we’ve used the ritual with other people and groups and prototype teams we meet with, and have been struck by how meaningful people find the experience. The response to the ritual has been so positive, the RECOVER team created a tool so that other people could explore similar questions within their own contexts. And I am left to wonder, what shifts might we collectively experience if more “professional” environments created the conditions to allow for rituals such as this one?”

— Miki Stricker-Talbot

Living in a moment of culture change

As the InWithForward team brought Losstenders into the Soloss prototype we very intentionally set out to have a palpable culture of wellbeing, to make the values behind that prototype evident in all our interactions, [could include planet cross-section principles image here] not just with the Losstenders but also the esteemed practitioners and community leaders we brought together for our Sounding Board (advisory group) as well. Frankly, some of the things we tried were right on the edge for me. They made me feel a little vulnerable, a little new age, a little silly. For example, we all lit a candle at the beginning of every Zoom session together, to create a sense of shared space, and ritual time. At first, I was almost always waiting for a Losstender or a Sounding Board member to say “are you for real?” But what ensued was actually a series of brilliantly meaningful moments, wonderful and unexpected relationships across lines of difference, and a real, shared vision that centred around the framework. I don’t know if it was a kind of Overton Window for emotion and connection talk, brought on by the pandemic. People didn’t seem riled by it, they didn’t assume a critical distance. They seemed nourished by an opportunity they knew they had a hunger for – not just intellectually, but in their hearts and souls.”

— Natalie Napier