Categories

The Connector Role is an in-progress prototype to figure out how to support more authentic connections between street-involved Edmontonians and the rest of the community. When we started, two things were pretty important to us: to be in Edmonton and to collaborate with street-involved Edmontonians. That’s because prototyping involves recruiting people to work closely with us to imagine and create through iterative rounds of testing.

Of course, Covid-19 disrupted our plans. Despite our team’s deep desire to get on the ground, we realized the pandemic was here to stay and it was important for us to accept and embrace virtual prototyping as the norm. Three members were in Edmonton, one in Vancouver, one in Peterborough and I was in Toronto. So what have we tried? And what have we learned?

First, a little context

This time last year, back when you could eat inside restaurants, we were slurping hotpot with Vernon. Confined to a walker, Vernon shuffled between the low-mobility shelter and the liquor store off 107A street in downtown Edmonton, sometimes losing track of time and space along the way.

The assumption was that folks like Vernon hadn’t just lost their way, but that the service system had lost them. So there was real surprise when, at the end of lunch with Vernon — during which he reminisced about growing up with his sister in Saskatchewan, going to the gym and working with his hands — he extracted a crumpled note from his wallet with a phone number for his case manager. He was uncertain of her name and her role.

Two years of ethnographic research and analysis with street-involved adults, stewarded by the City of Edmonton’s Recover Team, found folks like Vernon were seeking something more than services. They were seeking a deeper relationship with land and culture, self and community, human potentiality and the sacred.

So, what could it look like to co-design a role premised on connections out to these sources of wellness rather than just connections into services? That has been the starting point of our partnership with Reach Edmonton, with support from the City of Edmonton and Edmonton Police.

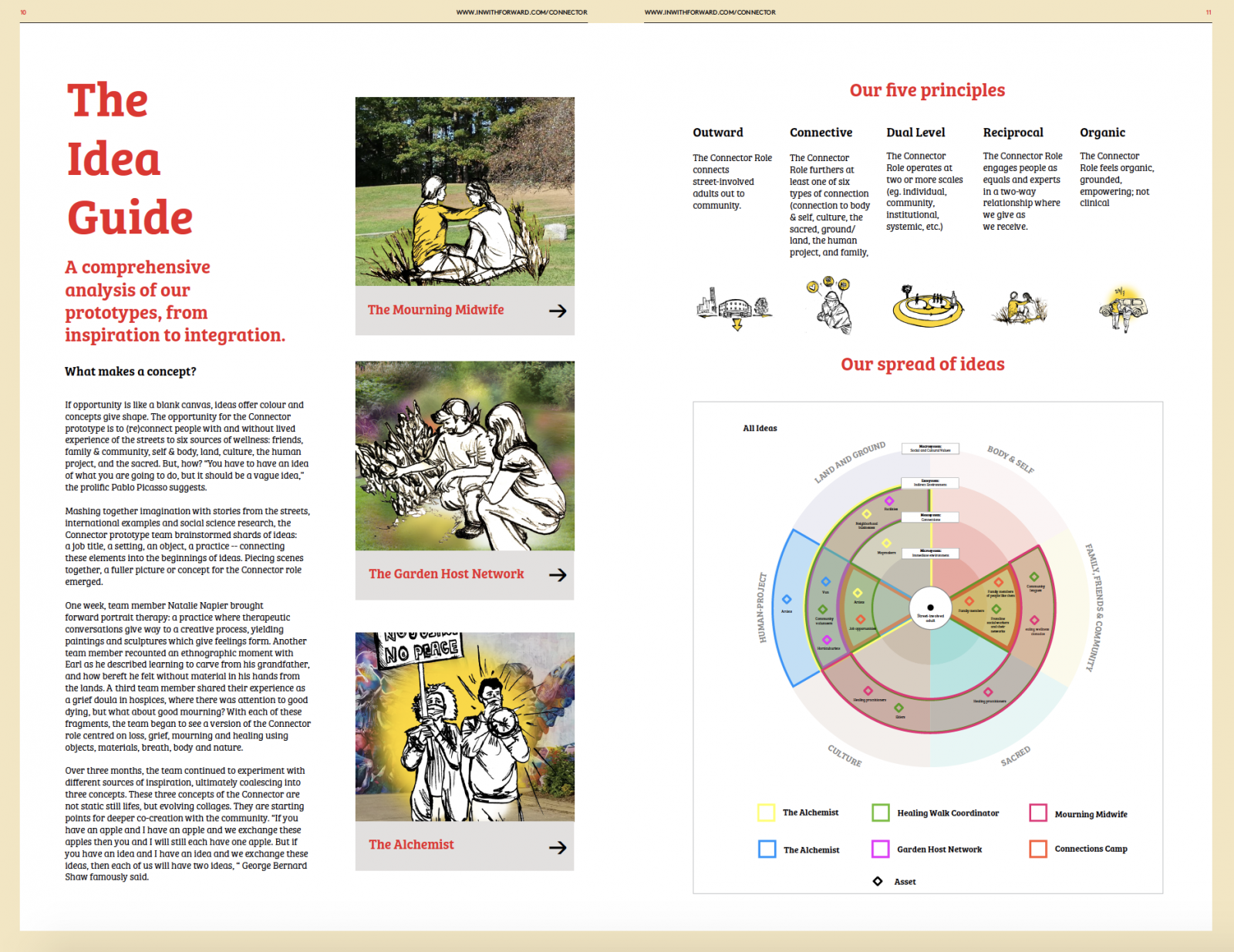

Three versions of a connector

Mashing together imagination with stories from the streets, international examples and social science research, we developed three different versions of a connector role.

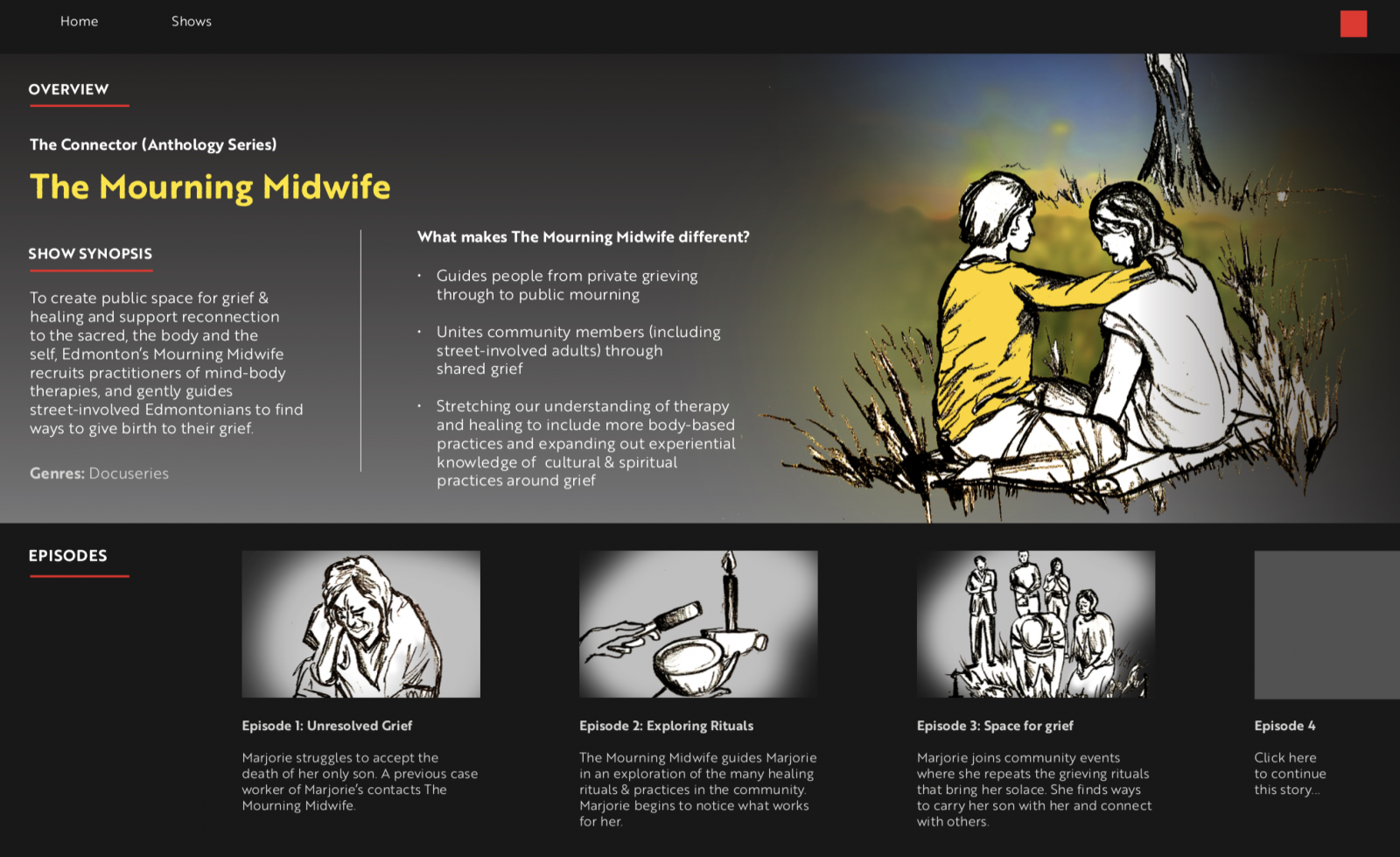

The Mourning Midwife catalyzes public space for grief and healing, and supports reconnection to the sacred, the body and the self. How? By bringing mind-body practitioners, elders, healers and community members living on and off the streets together for ritual and ceremony.

The Garden Host recruits and coaches a network of nature lovers, backyard gardeners and foragers to open-up natural spaces as sites of relaxation and retreat for folks contemplating change.

The Alchemist matches local creatives with street folks to reclaim and remake familiar places from their own perspective. Together, they make maps, public art, and installations that tell a different story.

Two rounds of co-design

But, how to bring alive these concepts and turn them into evolving stories? Our first attempt at co-design drew inspiration from Netflix. We likened each concept to a docuseries and visualized a narrative arc, inviting co-design participants to help us imagine plot lines and characters — including placing themselves into the sequence.

Perhaps it was too high concept. Co-design participants gravitated towards the storytelling, but struggled to step into the writer’s room with us to co-create the next scenes. Our polished looking materials felt hard to shoot down or improve, especially virtually.

Our second attempt at co-design has retained the narrative arc, but scrubbed some of the polish. Rather than slick visualizations, we produced three audio stories (working with voice actors from Boyle Street Community Services) with first person accounts of each concept. Alongside these audio stories, we mocked-up brochures with a range of value propositions to test what offers catch people’s attention. And we went outside (well, our indefatigable Edmonton team members Hayley and Jane did) to literally catch people’s attention. With hot chocolate, laminated brochures, Ipod shuffles, plenty of hand sanitizer and PPE, we’re finding ways to safely return to in-person engagement. There’s still no replacement for the spontaneity and surprise that comes from face-to-face interaction.

Three lessons learned

1) Be more careful about where to insert power

Subtle human interactions get lost when you’re prototyping over a screen. We lose the organic space to entertain multiple trains of conversations, the opportunity to indulge the spontaneous afterthoughts that pop up in unexpected moments, and the physical playground to jump into tactile tinkering. With online conversations, there’s often greater sensitivity to what to say and when to say it. People may be more aware of their own airtime in context to another. Therefore, when there’s any moment of silence to a request for reactions or responses such as “Any thoughts?” it’s important to keep in mind that it should not be interpreted as an agreement to anything. People may require other channels or forms to express themselves rather than being asked on the spot. It’s important for us to create more intentionality in creating space for individuals who we feel have not had as much airtime. This might look like checking in one-on-one with folks or setting up reflections as homework for the next meeting.

2) Don’t assume equal literacy standards

As a visual designer, Zoom has in fact heightened my attention to detail in visualizing the team’s thinking process. As we were prototyping potential artefacts and tools to test our emergent ideas with community members and street-involved adults, I recall feeling a stubborn impulse to make things larger-than-life, in order to catch our audience’s attention. However, a team member suggested that the audience we seek may not want or be able to read. Out of that discussion, we eventually landed on the idea of designing audio tapes to sonically paint a picture of our concepts. We surprised ourselves as we realized that it was not only a medium that felt accessible for street-involved Edmontonians to be a part of co-designing, but it turned out to be the most well received and engaging conversation starter on the ground as well.

3) Design more of an approach, less of an agenda

In order to enable our co-design partners in Edmonton to confidently stop and interview folks on the ground (acknowledging we could not lend our physical support), I initially suggested an agenda that followed a concise order, including notes on timing and conversation transitions under an assumption that a sense of structure and order could alleviate uncertainties. However, the team realized that the plan went out the window the minute we stepped out into the actual setting. People were asking questions from different directions, and they had wildly unpredictable schedules and attention spans which made ‘order’ in fact feel more stressful. Instead, we shifted our approach to thinking of our interviews as operating a storefront. As a team, we focused and developed the team’s confidence around individual artefacts so they are more prepared to start conversations based on whatever piques a passersby’s interest.