Categories

A stressful event that shatters our sense of security. ✔

A feeling of being helpless in the face of danger. ✔

Shock, denial, disbelief. ✔

Confusion, difficulty concentrating. ✔

Irritability, mood swings. ✔

Anxiety and fear. ✔

Withdrawal. ✔

Sadness. ✔

Numbness. ✔

We’re still very much in thick of the upheaval — and, with so many of our rituals for grieving and catharsis upended, how do we also lay the groundwork for our collective healing? How might we rebuild systems, recalibrate dominant ideologies, reset daily patterns, and rewrite social contracts to strengthen solidarity and resiliency whilst weakening marginalization and precarity?

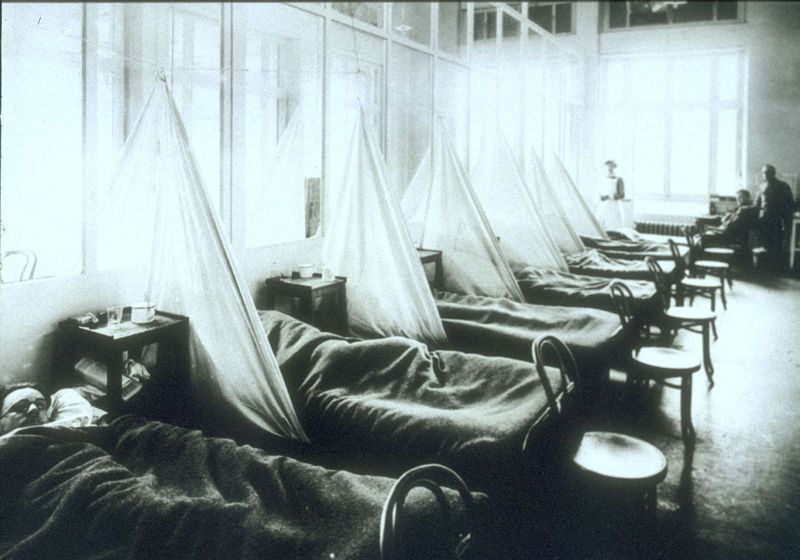

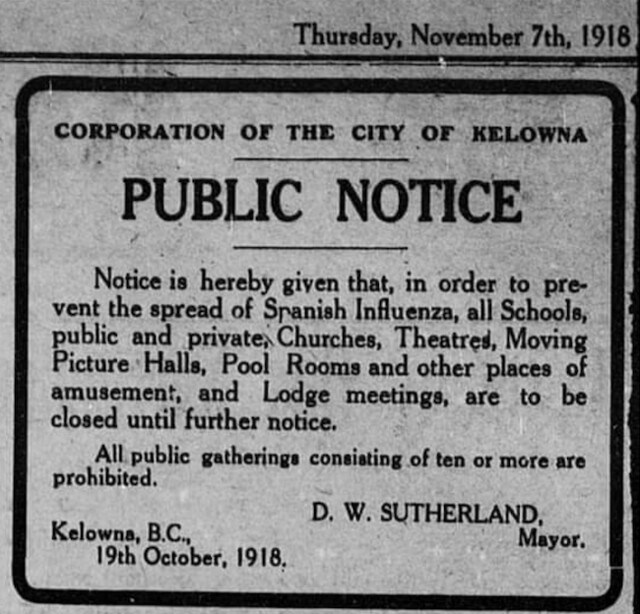

After the 1918 Spanish Flu, plenty changed. Author Laura Spiney writes, “The lesson that health authorities took away from the 1918 catastrophe was that it was no longer reasonable to blame individuals for catching an infectious disease, nor to treat them in isolation. The 1920s saw many governments embracing the concept of socialized medicine – healthcare for all, free at the point of delivery.” And yet, Spiney, also recounts the many left behind: “long-term invalids, including melancholics, who could no longer work…widows…orphans nobody wanted (from Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World).”

We constructed safety nets — some country’s far more perforated than others (yes, America), and began shifting trust and responsibility for care to an ever-growing cadre of trained professionals. The informal gave way to the formal. Writing in The Atlantic, Noah Kim details some of what was lost. “In many places, the loneliness and suspicion caused by the flu continued to pervade American society in subtle ways.” He quotes John Delano, a Connecticut resident and flu survivor: “People didn’t seems as friendly as before. They didn’t visit each other, bring food over, have parties. The neighborhood changed. People changed. Everything changed.”

One hundred and two years later, about a third of the world is under lockdown. We find ourselves confined to our homes and neighborhoods, clamoring to our windows, balconies, and lawns for some nightly camaraderie. 7pm comes with a bang. In Vancouver, like lots of cities around the world, we use pots and pans, cowbells and tambourines, and plenty of clapping hands to celebrate courage and commitment. It’s a rousing reminder we are not alone. It’s also the most connected I’ve felt to the city in the five years I’ve lived here.

This pandemic, like the one before, will profoundly change things. We cannot turn away from the cost of job loss, food insecurity, family strain, domestic violence, and more. Alongside large-scale economic relief, can we marshal some of the newfound neighborliness and tighten our social bonds to look after each other? Can we co-create radically inclusive communities where our shared strengths and vulnerabilities shape our trajectories more than the backgrounds that divide us?

We’re seeing five early opportunities going forward:

(1) Beyond Buildings

Libraries, schools, community centres, disability day programs, and so on are closed — but checking out e-books, sharing knowledge, exchanging skills, meeting new people, and accessing resources need not be. So much of current education and social service delivery is designed around physical buildings — but buildings too often exclude. Doors can be barriers. Opening hours can be barriers too.

Liberated from the building as the anchor point of activity, educational and social service providers can operate more as distributed platforms, identifying and leveraging community assets outside its doors. When Covid-19 finally retreats, how might we not only reopen our closed buildings but open-up our thinking to how we engage outside the four walls and nine-to-five culture that can be out-of-sync with marginalized people’s lives? (Note: A promising start is BC’s new safe supply guidelines, enabling folks facing addiction to receive take-home supplies of drugs).

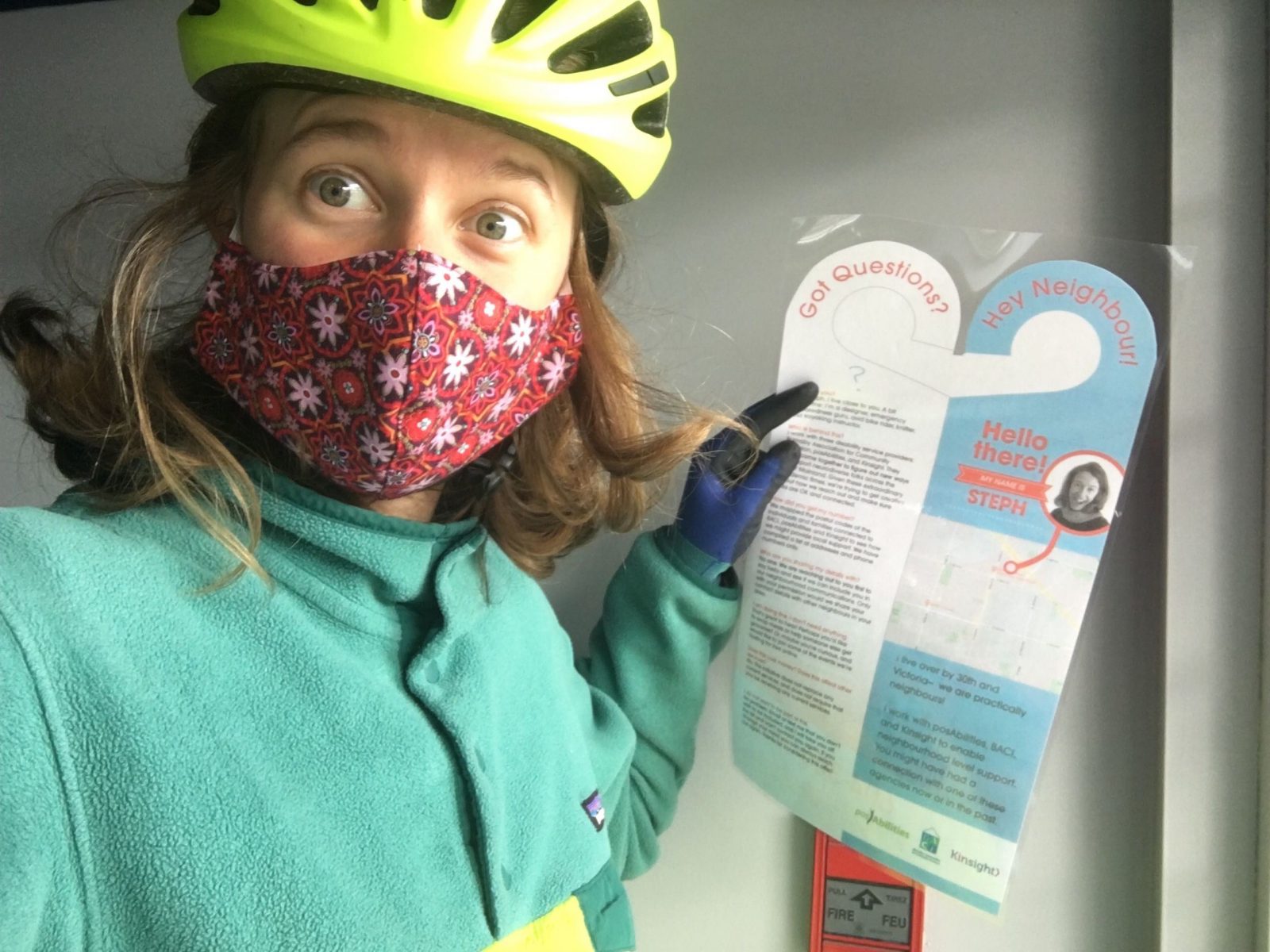

Along with our organizational partner, posAbilities, we’re using pandemic time to test a role called the Neighborhood Organizer. We’ve mapped where individuals and families with disabilities live, alongside agency staff, and started inviting staff to reach out to the folks in their neighborhood to check-in, facilitate connection, and broker food swaps. Just because day programs and facilities are temporarily shut does not mean support can’t keep flowing at a hyperlocal level. What could it look like to start matching individuals, families and staff within the neighborhoods they already live?

(2) Informal Relationships

Within a week of stay-at-home orders, over 720 mutual aid groups sprung up across the UK to facilitate neighbour-to-neighbour help. Next Door accounts, Facebook groups, and quickly-coded apps are facilitating local exchange and social contact across the globe. People are organizing — without cumbersome bureaucracy, rigid structures, and layers of approvals and protocols. Perhaps we’re re-learning how to directly engage with our fellow humans, freed from some of the formalities that can (inadvertently) disempower. How can Covid recovery embrace informal roles and relationships, rather than supplant it? How might professional services shift from programmatic to platform thinking, moving from directly providing care to providing tools for mutual help and self-organization? While the tendency post-Covid could be for professional organizations to adopt more policies, procedures and protocols, how might we design risk-mitigation strategies that appreciate and harness the power of the informal?

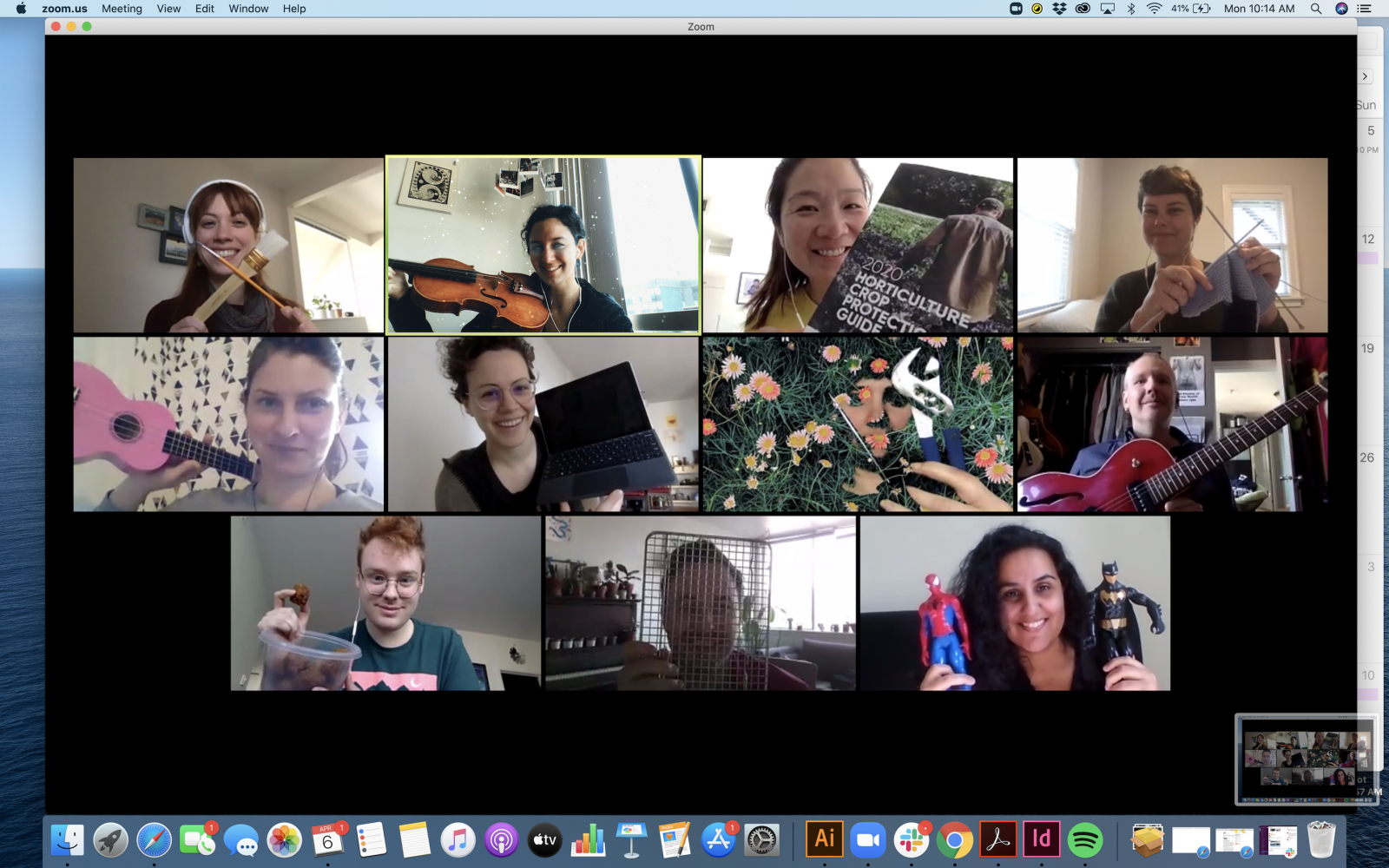

Together with our organizational partner, Options Community Services, we’re using pandemic time to test Humans Understanding Humans (the online version), where we bring together professionals and newcomers to Canada to learn from each other. Rather than replicate the traditional professional-client relationship, we’re brokering (digital) moments of curiosity and humility. The professional isn’t the all-knowing expert. The newcomer isn’t the hapless student. Using a deck of cards to pull apart cultural perspectives, both the professional and the newcomer are sharing their lived experience and practicing how to communicate with each other, on equal grounds. What could it look like to relate as co-learners?

(3) Renegotiated Boundaries

Walmart’s announcement that tops are more in demand than bottoms says so much about the current blurring of private-public divides. One moment, we’re on a work call. The next moment our family members are strutting into the frame (and the fray). The secret is out: our lives are messy and our sanity is fragile. And that is refreshingly honest. Seeing people in their homes, dishes and dogs and kids and all, paints a more fulsome picture of who we each are. Context brings understanding. Gone is some of the performance — and in its place is a rawness that can foster trust and authenticity. How might Covid-19 open up the space for us to renegotiate private and public boundaries, and find a more frank balance between our many roles and hats?

In partnership with Burnaby Association for Community Inclusion, Kinsight and posAbilities, we’ve used pandemic time to launch CoMakeDo, a curator of daily digital gatherings for neurodiverse folks, bringing together new online offerings from Kudoz, Real Talk, Meraki, and more. In one of our first gatherings, Caitlin introduced us to Phyllis and Meredith, two cute and curmudgeonly hedgehogs. Caitlin’s parents joined from Ontario — along with about 15 other individuals and family members. We watched with delight as Phyllis and Meredith scurried across Caitlin’s apartment floor, gaining a window into day-to-day life with hedgehogs as pets. Sure, Caitlin has a professional role as a disability support worker. But, in sharing her creatures and context with us, she was so much more than her role. What could it look like to embrace our fuller selves?

(4) Place Rituals

Whether it’s stepping outside to make noise for health care workers, pasting cut-out rainbows to windows, or placing teddy bears in gardens, being bound to our houses has reacquainted many of us with the space we call home. Removed from our usual rhythms, we’ve found reason to pause and engage in seemingly small acts imbued with shared meaning. Even our online engagements offer opportunities to foster collective attention. When we eventually re-emerge from lockdown, how might we bring a spirit of joint action into our day-to-day? How might we curate more rituals of belonging in our families, on our streets, within our communities, organizations and teams?

Together with a small group of Filipino families, we’re releasing I want to tear out your hair. Caught in the demands of the every day, it’s pretty hard to make time for family conversation. For so many reunified Filipino families, it’s next to impossible. Mom might be working two or three jobs. Now, with kids and parents sharing more space, how might they also share feelings? Families can sign-up to watch our mini-film series, and receive a short video by text message every day for a week, plus some handy activities from families for families to spark conversation and connection.

Working from home, our team has also been experimenting with rituals for conversation and connection. Mondays, we huddle, splitting off into pairs to write, draw, and set intentions for our week. A daily dasher keeps our energy up, with quick exercises (e.g writing google reviews of our homemade lunches) and vigorous check-ins (disco workouts). Friday, we play and reflect, often dressing-up or toasting to demarcate the end of our strangely new normal weeks. These rituals are a hearty source of laughter and creativity — and as silly as they sometimes feel, they are also an outlet for sense-making and meaning-making.

While so much of our ethnographic fieldwork with positive deviants in marginalized communities has taught us the power of rituals for meaning, purpose and connection— whether it’s a smudging ceremony, an informal support group held at the back of a Dairy Queen, a daily walk in the park — so much of our day-to-day realities are overtaken by banal tasks and more urgent priorities. What could it look like to reclaim time and space to feel a little more part of the whole?

Digital Access

The mass migration from the physical to digital world exposes real gaps, and reinforces existing divides. Older adults and those living with disabilities are populations digitally left out. While 91% of Canadians reported using the Internet in 2019, only 71% of seniors went online. Individuals with disabilities are about three times as likely as people without a disability to say they never go online. Indeed, disabled adults in the US are about 20% less likely to subscribe to home broadband, own a desktop computer, smartphone or tablet (citation). With libraries and community centres now shut, there’s even less access to computers and Internet. So many of the street-involved adults we’ve spent time are active online (Facebook is a real connector), but rely on shared computers or free wifi from places like McDonald’s and Tim Horton’s, where we can no longer congregate.

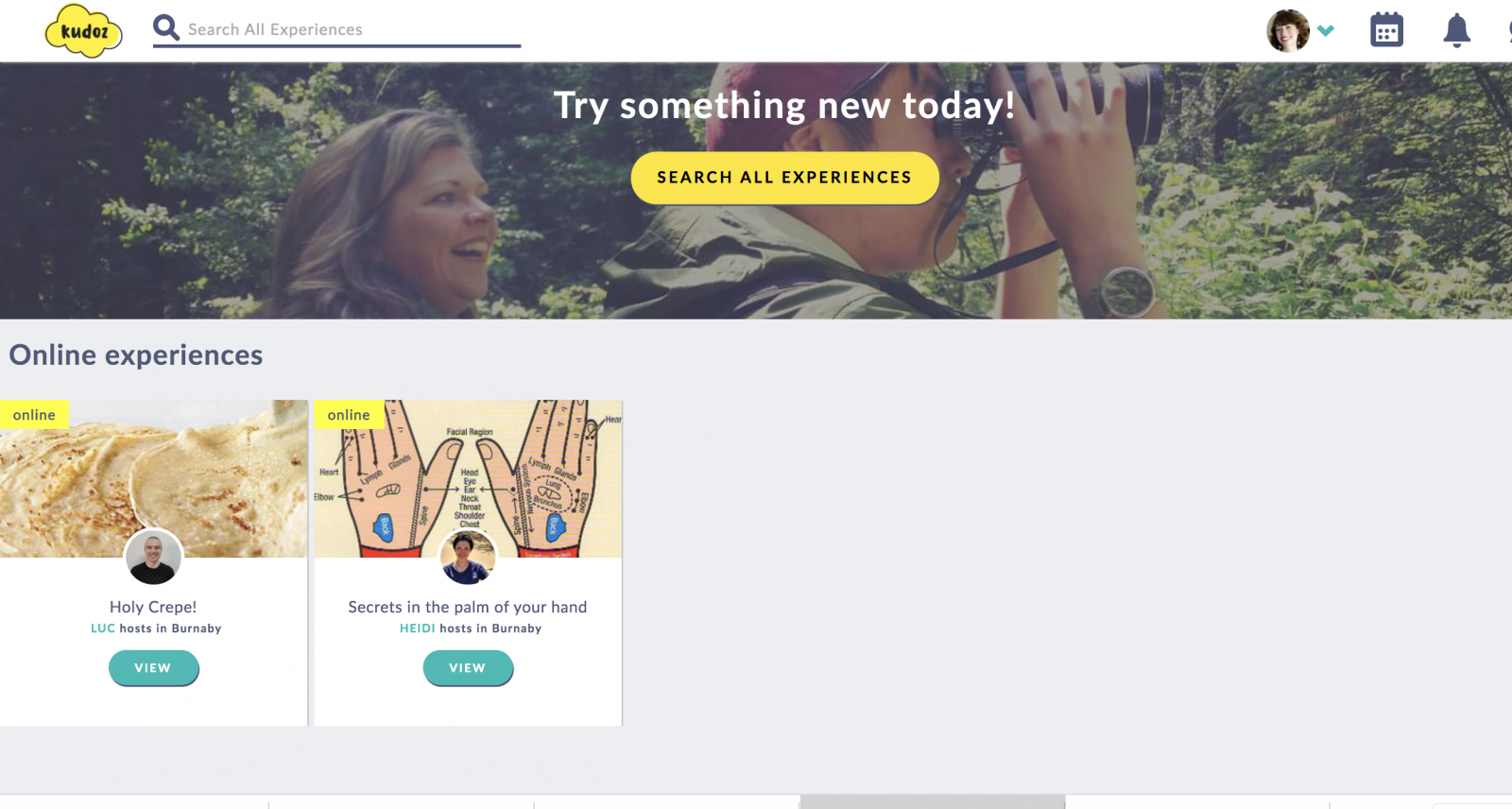

Internet access should not be a privilege afforded to those who can pay. While a number of schools around the world are investing in Chromebooks and wifi devices for students now at home, how might we similarly invest in digital infrastructure for marginalized adults outside the classroom? Access to and capacity to use equipment is something we’ve had to build into the design of Kudoz.

When we decided to build an online catalogue for individuals with developmental disabilities, we simultaneously had to organize loaner devices and create a new role, the Tech Fellow, to offer customized tech coaching. While the intent of the Kudoz online catalogue was to connect people for offline experiences, we’ve now pivoted to provide 1:1 digital experiences. Tech coaching is now even more crucial. Going forward, how might technology be conceptualized as a basic need? If prescription drugs can be delivered to you to keep you physically well, might digital tools also be dropped-off to keep you socially well?

One of the most powerful parts of this pandemic is just how shared our experience is. Staying at home to flatten the curve has perhaps also flattened our understanding of economic precarity, isolation, and loneliness. For far to many folks, this was their reality prior to Covid-19. Let’s not make it the reality we return to after Covid-19.

Curious about what we’re trying? Want to get involved?

- No matter where you are in the world, you can host a group gathering via CoMakeDo or a 1:1 experience via Kudoz. We can help shape the session around whatever you love to do: stretching, drawing, cookie baking, improv, gardening, storytelling, playwriting, and anything and everything else!

- Get matched to a newcomer in Canada via Humans Understanding Humans. Practice inter-cultural communication, and help us iterate the interactions.

- Connect us to Filipino families to test I want to tear out your hair! and help us create new conversational rituals.