- #1/Inspirational. So say some designers who’ve seen a recent presentation of our work at the global Service Design Network conference. Ironically, that presentation describes how we build partnerships to hold the creative tension necessary for addressing the roots of marginalization: estrangement, shame, dislocation, and disconnection. Keep reading for the irony.

- #2/Accurate, except for the cat part. Bonnie looks over the story we’ve written about our time on the streets together, documenting how she uses crisis services. She’s taken aback by seeing her words played back. What we’ve written is mostly true, she says, except for that part about leaving behind a white furry cat during her last eviction. She never owned a cat.

- #3/Empowering. That’s how Alexa describes what it’s like to spend the day sharing her experiences under the Mental Health Act. “You don’t expect that people will want to listen to you.” After 21 hospitalizations, Alexa is used to answering doctors’ questions. But, engaging with us felt different. Free from assessments, diagnoses, and professional agendas, Alexa says she wrestled back some control of her story.

- #4/Unrealistic. A project coordinator, after seeing thirty early ideas visualized from a week of research, calls them “unrealistic.” We offer up the ideas as a prompt for further research and co-design. To the coordinator, why consider the ideas if they simply cannot happen?

- #5/Irrelevant. A manager browses an ethnographic dataset of ten stories, and expresses concern with the small sample size. “We don’t make policy by anecdote,” they firmly note. There is little point in discussing emergent themes if they aren’t statistically generalizable.

- #6/Untenable. A chief executive of a non-profit pulls the plug on a two-year partnership without warning or dialogue. Their staff weren’t bought into the solution we’ve been co-producing with recently reunited Filipino families and Arabic-speaking newcomers. Community-led prototyping, they’ve decided, is not a strategic priority. Staff-led innovation, they argue, is more deserving of time and dollars. Workshops and trainings for staff are more palatable than testing new roles and functions in the community.

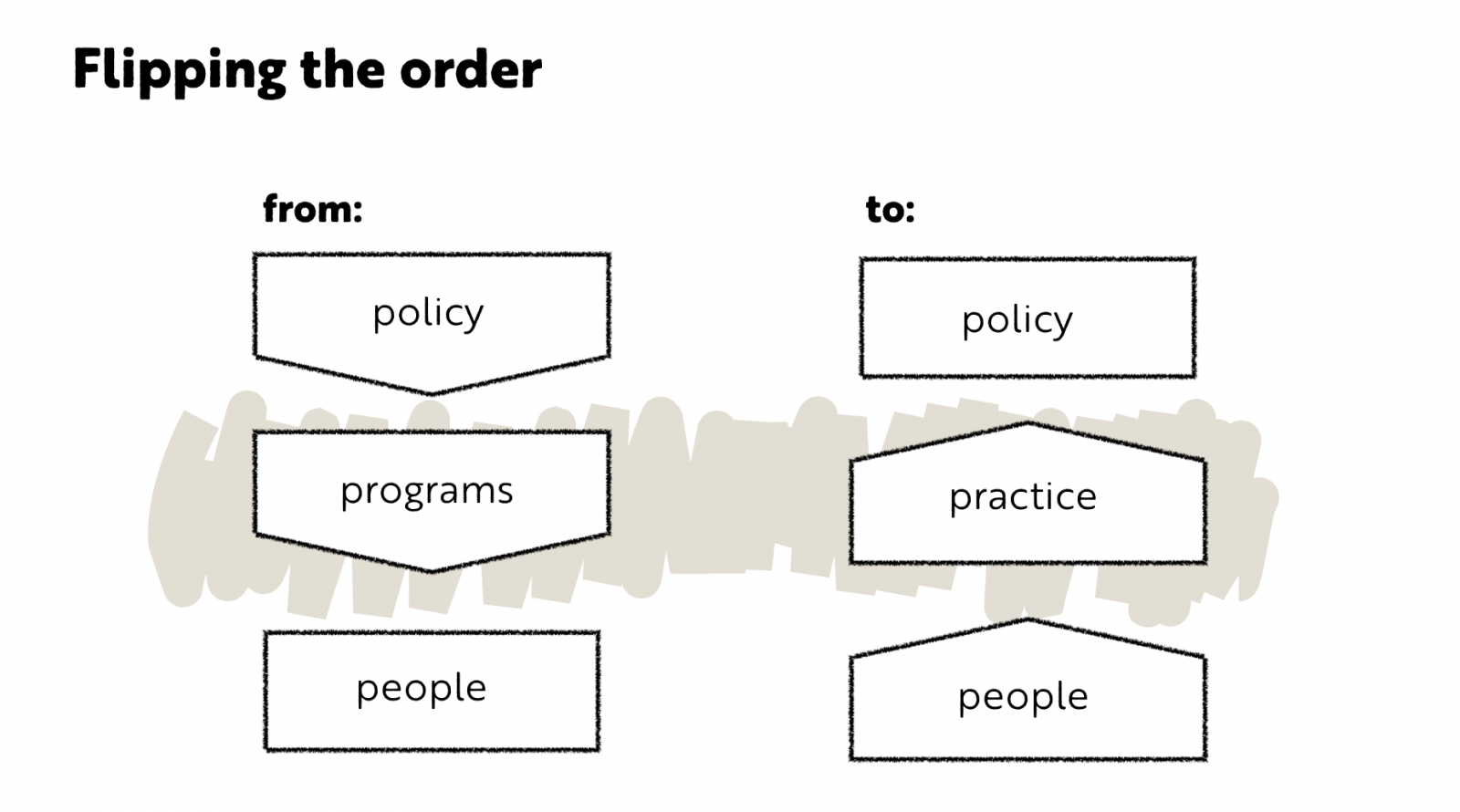

Our approach is premised on redistributing power and control between the top and the bottom because we see power and control as the nutrients of personal and social change. We try to flip the policy process on its head and start with what people need and want, not with what service providers or funding institutions need and want.

Inevitably, that means calling into question contemporary orthodoxies so entrenched that they are confused as unassailable facts rather than contestable theories. So it should come as little surprise when service providers and funding institutions express concern with what emerges from our groundwork— especially given they are footing the bill. A business model which asks the current system to pay for its critique and creative dismantlement is certainly cheeky, if not unduly problematic. Organizations mostly want to contract us for innovation, not partner with us for revolution.

Social worker Steven Wineman, in his deliciously straight-talking book, The Politics of Human Services, lays out the cardinal conundrum:

“The helping professions draw their existence from personal misery and from the political/economic/social conditions that underlie problems. This tends to create a subtle but profound investment in the status quo. Even worse, psychosocial organizations tend to define and refine personal problems in the service of their own survival and expansion…Most social service professionals are earnest and well-meaning people, hoping to do good; but the plain flat is that the elimination of poverty would cost most of them their jobs, and the proliferation of the consciousness and mechanisms needed for emotional self-care and mutual aid would drive the last nail into the profession’s coffin. This produces a structural conflict of interest between social service providers who embrace a professional identity and the people they are supposed to serve…It is only if service providers understand their purpose as the creative dismantling that … they can fully embrace the erosion of oppressive conditions and the growing capacity of people to care for themselves and nurture each other. This is a reasonably tall order…”

What surprises me isn’t the disquietude system stakeholders hold — given what is at stake, their apprehension is understandable — but how infrequently we’re able to have conversations that get to the heart of the matter. So much of modern managerial discourse focuses on process (efficiency, expediency, fairness) and so little attends to content (power, justice, equality). We’re watching in real-time as supporters decry Trump’s impeachment hearings on the grounds of an unfair process, unable or unwilling to comment on the substance of the inquiry. And while the Canadian social sector is constitutionally unlike bombastic Trump minions, I see a familiar tendency at play: consternation with process as a way to bypass meaningful engagement with content. Both process and substance deserve meaningful debate. Where is the capacity to identify and unpack a core idea, recognize its historical roots, and entertain the plausibility of alternative thought?

Economist E.F Schumaker, writing in the 1970s, neatly summarizes the challenge:

“All philosophers — and others — have always paid a great deal of attention to ideas seen as a result of thought and observation; but in modern times all too little attention has been paid to the study of ideas which form the very instruments by which thought and observation proceed. On the basis of experience and conscious thought small ideas may easily be dislodged, but when it comes to bigger, more universal, or more subtle ideas it may not be so easy to change them. Indeed, it is often difficult to become aware of them, as they are the instruments and not the results of our thinking — just as you can see what is outside you, but cannot easily see that with which you see, the eye itself…”

When we examine the ten pieces of feedback we regularly receive from organizations and institutions, four bigger and more universal ideas parade beneath the surface: notions of (1) desirability, (2) feasibility, (3) validity and (4) ethics. These are the ideas we are hungry to talk about.

Top ten pieces of feedback we receive:

- We already do this.

- We tried that once and it didn’t work.

- We don’t have time.

- Our staff feel disrespected.

- Your ideas aren’t practical.

- There isn’t a sufficient cost-benefit analysis.

- This isn’t scalable.

- The data isn’t representative.

- The data isn’t truthful.

- Our clients are too vulnerable to participate.

- Research isn’t safe.

Notions of desirability

- “We already to this.”

- “We tried that once and it didn’t work.”

- “We don’t have time.”

- “Staff feel disrespected.”

For something to be desirable, it must be attractive, pleasing, preferable. The question is, according to whom? Beauty, Shakespeare reminds us, isn’t so much fact as judgement. Writing in 1588, in Love’s Labour Lost:

Good Lord Boyet, my beauty, thought but mean,

Needs not the painted flourish of your praise:

Beauty is bought by judgement of the eye,

Not utter’d by base sale of chapmen’s tongues

When staff and managers of social-serving organizations utter displeasure with our process, what can we learn about their preferences? Comments like “the process is too demanding” or “too destabilizing” reveal how ease and certainty get bundled together with pleasure and preferability. Take the timing of our processes. Often, bottom-up research and design work unfolds outside of conventional working hours. Getting to know stretched newcomers, working two or three jobs, might require late night intercepts on the bus or early Sunday morning chats before church. Such a schedule is usually deemed undesirable to paid staff, whose lives are oriented around a 9-to-5 schedule, and desirable to unpaid newcomers, who otherwise could not participate. Should our processes cater to the paid or the unpaid? Should what is desirable for the professional trump what is desirable for the community member? And should desirability be the determining factor for staff engagement — or do other factors like learning and purpose deserve more weight? As Geoff Colvin writes in his book, Talent is overrated, “Deliberate practice is often the opposite of enjoyable.”

Deliberate practice can be regrettably elusive. When staff suggest our work is “useless” because they already do what we’re doing, the assumption is that language matches intent. Two programs might share the same title — lets say, isolated seniors program — and diverge in their intent and interactions. Rather than summarily dismiss ideas that sound like each other, how might we take the time to understand what’s behind the words? Do we share a common philosophy? Are we pursuing similar outcomes and determinants? Are the roles, relationships, resource flows and power dynamics the same?

Recently, a non-profit launched a podcast with Filipino families, based on our ethnographic research findings. Around the same time, we began prototyping media content for newcomers. Our prototype was soon perceived as unnecessary and ultimately undesirable. Beneath the shared language of “podcasts” and “media content” was a different purpose and logic. While the podcast sidestepped the thrust of our research findings and perpetuated the dominant newcomer narrative (one of hard work, deference and economic success), the media content we aim to co-produce sources and shares alternative newcomer narratives. These are stories which allow for disappointment and frustration with Canada, and permit a plurality of feelings, values, decisions and lifestyles.

It’s all too easy to conflate form and function: to treat all podcasts, websites, apps or programs for marginalized users as more or less the same, and miss what the podcasts, websites, apps and programs are for. Plumbing beneath the banality of our everyday language takes curiosity and discernment; and that’s more time consuming and cognitively taxing than just taking words at face value. Apples and oranges are both fruits, right, so must we really understand the differences? Rather than revel in the challenge of picking apart words and ideas, these thought exercises are often debased as “academic” and “intellectual” and labeled as “time consuming” and “unnecessary.”

So when staff decline to participate in bottom-up research & design, we don’t see that as an outright failure of our process so much as an opportunity to explore what gets categorized as necessary, relevant and desirable work. It may very well be that our process is needlessly difficult, poorly conceived and brusquely communicated, or it may be that our process chafes against modern conceptions of work and want.

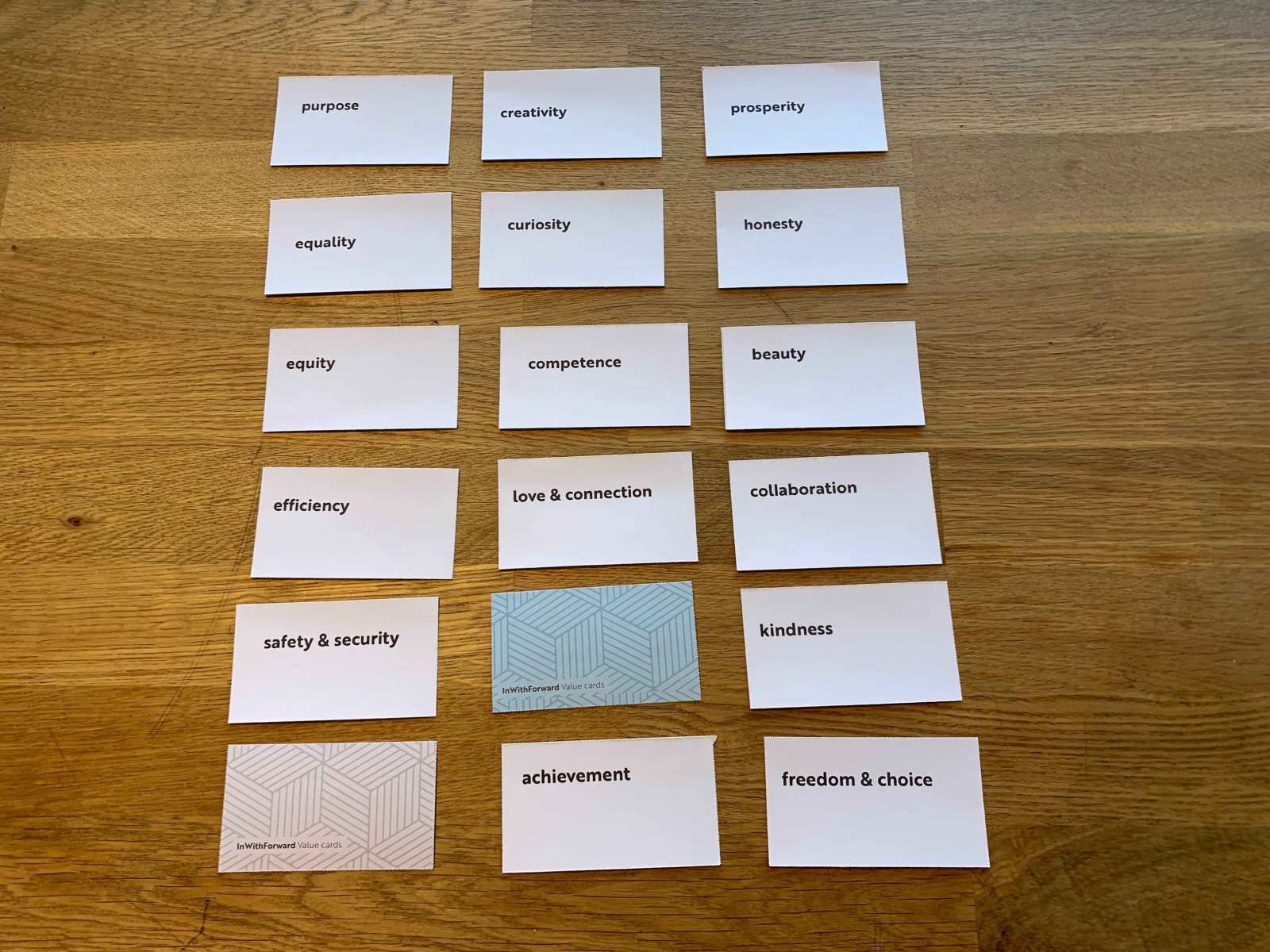

In the past, when we’ve facilitated exercises to unpack the purpose of work with frontline social services, three values have consistently topped the list: loyalty, kindness and respect. Challenge, courage and adventure are frequently bottom of the list. To be clear: there is no right or wrong value. Naming and understanding the origin of our values can help to extract who and what they are in service of. When do our values protect our own interests? When do our values accommodate others’ interests?

These aren’t questions to dismiss as pedantic. Working in the social sector should not give us a free moral pass. If anything, working in the social sector demands more careful and frequent scrutiny of what we do and why. What’s disheartening, then, isn’t when staff share their reservations with the process, but when inquiring about values and practices is construed as a sign of disrespect, antithetical to “kind” social service culture and “polite” Canadian conflict avoidance. When critical inquiry is rebuffed, and immediately interpreted as aggressive and arrogant, we lose generative space. Possibility is shut down.

Possibility comes from making room for alternatives. In narrative therapy, individuals practice separating their identity from the problems they experience. For example, a person living with alcoholism isn’t an alcoholic. They are a person struggling with the alcohol. This creates space for new identities and pathways to form. In the social sector, professionals have limited practice separating their identity from the ideas du jour. Deconstructing long-held beliefs can stir-up feelings of incompetence. And incompetence is our psychological third rail. Rather than respond humbly to that which we do not know, we are hardwired to cling to what we do know. Taking offense can easily overtake engaging honestly and reflexively. Without courageous leadership to hold space for both doubt and curiosity, bottom-up research & design work is frequently jettisoned in favor of more palatable professional development.

Notions of feasibility

- Your ideas aren’t practical.

- There isn’t a sufficient cost-benefit analysis.

- This isn’t scalable.

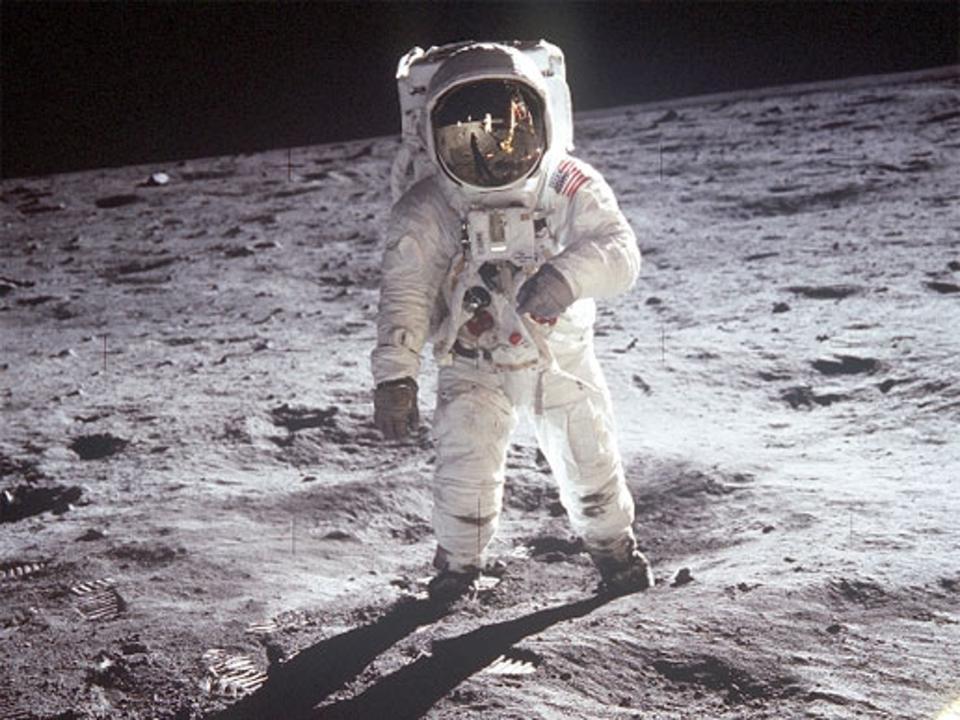

To be pragmatic is to deal with things realistically. But, what is realistic? Putting a man on the moon wasn’t exactly realistic. But, it became realistic. Engineers, mathematicians, scientists and politicians constructed a new reality, rather than accepting the existing reality. What’s transformative is rarely pragmatic. Disrupting the status quo requires poking holes in the paradigm, rewriting the rules, and creating a new normal.

So when stewards of current systems lament that our ideas aren’t practical, we agree. Our remit is to re-imagine what could be. We seek to make next practice, not reinforce best practice. Of course, when the ideas of the future are judged by the standards of today, they do not fare well. So when non-profits and funders, seemingly spellbound by social innovation, reject ideas on the basis of present-day premises, we must call out the incongruence.

Economic growth is very much the premise of the day. We value what we can put a price on. An adult learning platform for individuals with disabilities has value if it reduces demand on the system, lowering the costs of benefits and the uptake of services. Improving newcomers’ sense of self and future has value if acute health care utilization drops, and employment increases. People matter insofar as they are productive cogs, minimizing costs and maximizing income.

Social finance techniques like Social Return on Investment (SROI) play into dominant economic frames; they attempt to put a price on intangible benefits like social inclusion and hopefulness. Cost savings are the proxy. Hopefulness can be measured in terms of productivity: how many sick days hopeful people save, and how many more widgets hopeful people produce. The idea that hopefulness matters, not because it makes us more productive, but because it makes us more content and more peaceful factors little into our numeric calculations. Scholars like E.F. Schumaker argue that one of the more insidious assumptions of modern times is that prosperity brings peace. For Schumaker, permanence — not relentless growth — matters most.

Growth, not permanence, is very much on the minds of most who write the checks. “How will this idea scale?” is one of the first questions governments and foundations ask us. Investment is often only deemed worthwhile if the idea can grow and reach more people for less unit cost. But we must be prepared to ask: to what end? What if the power of an idea lies in its localization — in how it mobilizes community and engenders social solidarity and trust? At a time when social isolation is as deadly as smoking, how might we come to recognize the value of small-scale enterprise and neighborly networks? How might we come to see that bigger isn’t always better, and small is also good?

Notions of validity

- The data isn’t representative.

- The data isn’t truthful.

When stakeholders suggest our research and ideas aren’t valid because our sample size is too small and our data comes from “unreliable sources” (i.e people with drug addictions, mental illness, and memory loss), we must wrestle with concepts of validity, reliability and truth. Truth, the dictionary tells us, is characterized by realism.

But, our understanding of what is real is strongly rooted within time, place, and culture. It is not fixed. The prevailing Western paradigm — that there is one reality which only scientific knowledge can reveal — only emerged in the 19th century. “Positivist research methodology,” writes Professor Fadhel Kaboub, “emphasises micro-level experimentation in a lablike environment that eliminates the complexity of the external world …[but] those results may lack external validity. That is, the relations observed in the laboratory may not be the same in the more complicated external world where a much greater number of factors interact.”

Interdependent relationships are at the heart of alternative ways of knowing about the world. Indigenous scholar Leanne Betasamosake Simpson describes the practice of debwewin, or producing truths, as rooted in her body and life, land and story. She writes,

“As political orders, our bodies, minds, emotions and spirits produce theory and knowledge on a daily basis without conforming to the conventions of the academy, and I believe this has not only sustained our peoples, but it has always propelled Indigenous intellectual rigor and propelled our resurgent practices.”

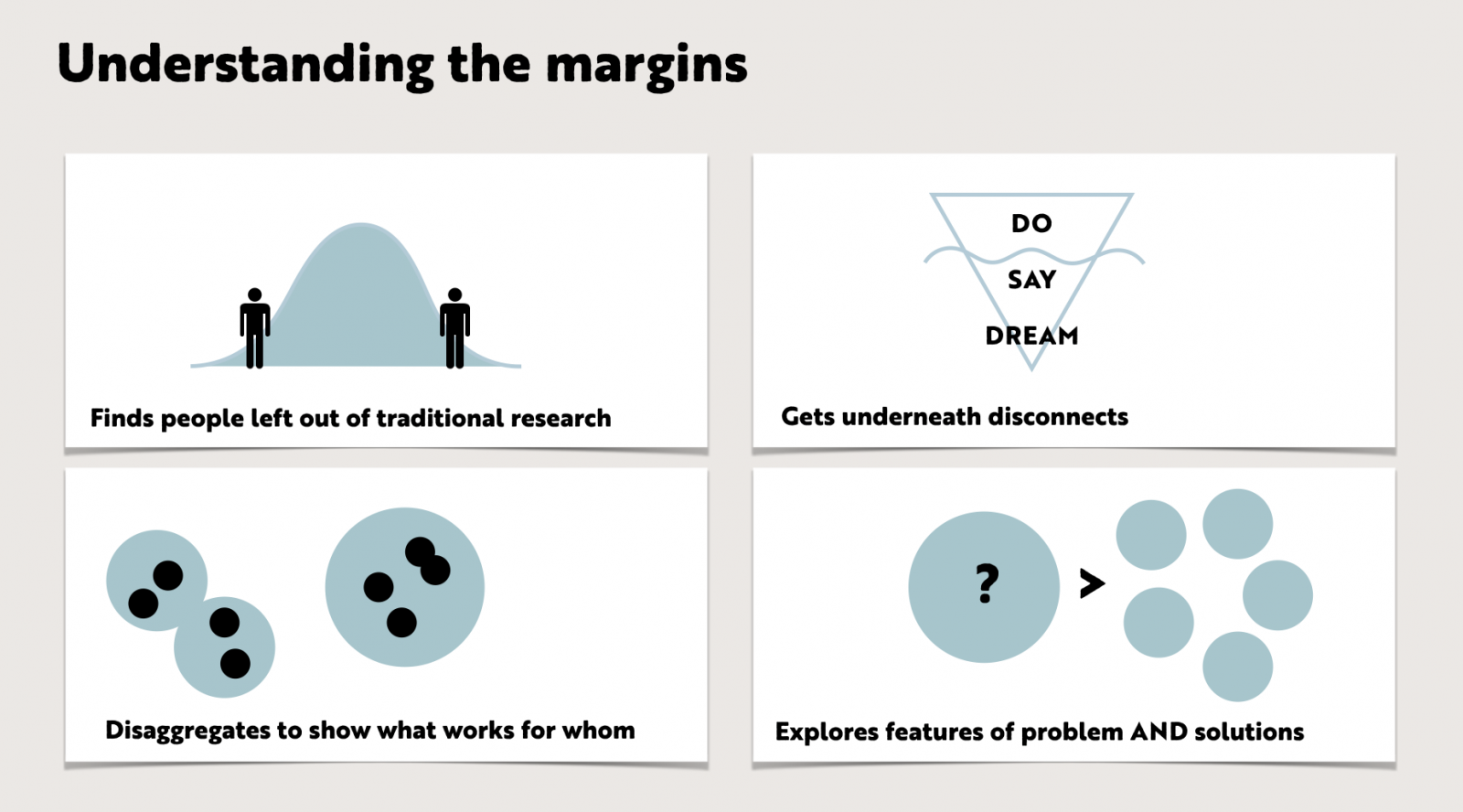

The notion that there isn’t one truth to find (positivism), but multiple truths to create (constructivism) is core to InWithForward’s research and design practice. Addressing the “social problems” that give funders and service providers their money & authority first requires understanding the multitude of ways these “social problems” are experienced and expressed. Where representative samples favor generalizability, purposive samples (the kind we go after) prize particularity. We see no two contexts as the same. In the details emerge insights and opportunities.

Data that dives deep into the details of ten individuals is no less true than statistical snapshots of one hundred individuals. Where statistically generalizable data might tell us about the average experience, it cannot tell us how and why marginal experiences exist. Paying attention to the ends of the bell curve (often lopped off as anomalies) is key to our mission of recalibrating power and control.

Quite frequently, system stakeholders question whether “the marginal” are right. They read a story of a person whom they know, and dismiss their version of events. “That’s not how it happened,” a professional might say. “Or there is so much more to the story than they told you.” We see disconnects and inconsistencies as new lines of inquiry: what do they say about social expectations & norms, power & control, memory & choice, performance & authenticity? Situated within an empirical paradigm that many aren’t cognizant of, too many professionals prefer to be arbiters of a single truth than explorers of multiple truths.

It’s far safer to see truth as black and white — because questioning what professionals know, and how they know it, can raise profound doubts about the basis of their interventions. When a well-intentioned professional rejects a benefit claim, or removes a child from a parent’s care, or puts an adolescent under the Mental Health Act, they are making a judgement about what is true and what is right. Accepting that there are multiple truths goes against much of what our welfare systems have trained us to do: arbitrate and administrate. Transforming our welfare systems must start here.

Notions of ethics

- Our clients are too vulnerable to talk.

- Participation is unsafe.

Bundled up with questions of veracity come questions of vulnerability. Much of what gives human service professionals legitimacy is their credentialed expertise in assessing, diagnosing, treating and managing clients, patients or participants. For all the contemporary buzz around “strength-based approaches,” what characterizes a “client” “patient” or “participant” is their need to be helped. Indeed, addressing needs is still the basis for the professional relationship. And when mired in sorting out needs and fixing problems, it’s hard not to see your client, patient or participant as someone who must be protected from future harm.

Against this backdrop, it makes sense when professionals express worry with their client’s engagement in our research process. What will emerge from our process is uncertain, and uncertainty is often perceived as harmful. When we ask professionals to introduce us to their clients, more often than not, the answer is no. A frontline worker told us that raising the research opportunity with her elderly clients would be manipulative: “They are so isolated that they may say yes just to talk to you, without knowing what the consequences are.” Ensconced in a vulnerability paradigm that is cloaked in the language of strengths, it must be scary to give people choice, particularly when you doubt their capacity to make good choices but aren’t supposed to talk about their deficits. Saying no is just so much simpler!

What’s worrisome is when professionals raise ethical concerns with our process, but not with their own. Yes, our process does raise important ethical considerations about personal agency, control, and informed consent. And so does theirs. That is the richness of ethical conversation, where there are rarely absolutes, only grey and color zones to explore. When does it make sense for a professional to speak for a client? When is a client vulnerable: is it a fixed state, or an environmental state (New research on dementia, for example, suggests that in the right settings, individuals can maintain and even regain some skills)? How do we determine whether professionals are acting in the best interests of their clients? When should and shouldn’t a person be presented with an opportunity to participate? How do we measure the risks of participation — to the person, the professional, and the institution — and whose risks matter most, when?

These are the questions that substantively matter. Castigating research and design processes as unsafe, inappropriate or unethical may be less demanding than honest dialogue, but it most certainly doesn’t make people safer or shield institutions from doing harm. Disengaging from tough conversations doesn’t let any of us off the ethical hook: it only raises the moral stakes.

The courage to talk, really talk

Tough conversations really aren’t easy. They are deeply unmooring. How unsettling to be confronted with ideological structures we might not have realized existed, but which are the source of professional legitimacy and competency? Questioning the truths we hold as self-evident stirs up self-doubt, humiliation and shame — all emotions we humans work pretty hard to suppress.

But, holding space for the ugly emotions goes hand-in-hand with excavating and then generating fresh ideas.

Our team constantly stumbles here, too. How do we create room for the feelings, without letting them subsume us? How do we listen to the feelings, and use them to figure out how to be and do differently? We learn as we go, giving space for moral quandaries, worries, methodological questions, celebrations, and moments of pride every Friday morning. Some weeks we hit a reflexive sweet spot. Many weeks we merely go through the motions.

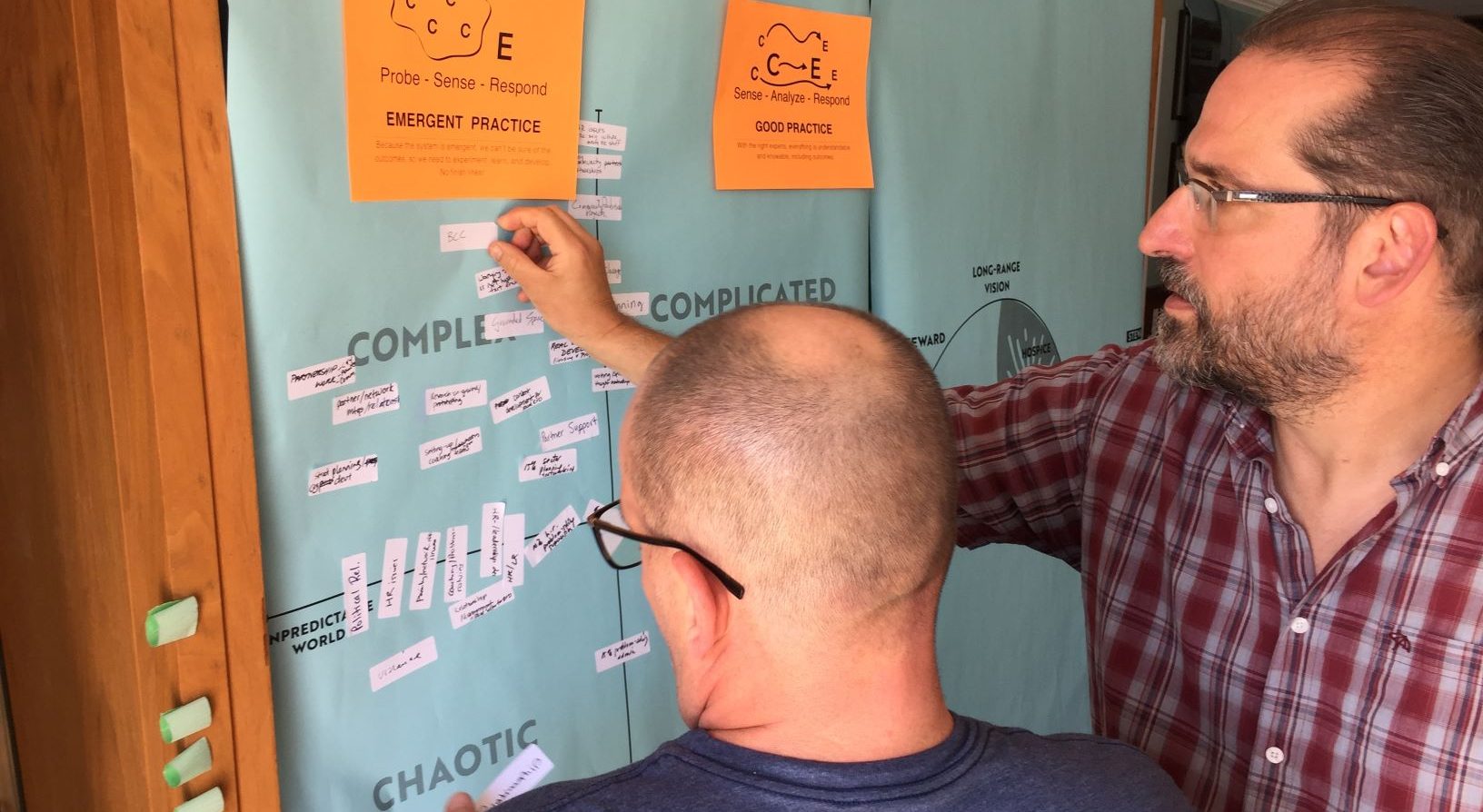

Given the emotional underbelly of bottom-up research and design work, it’s little surprise that the rhetoric of innovation has taken hold. It’s positive and optimistic, playing into the presumed linearity of progress. Over the past five years, we’ve worked with over thirty non-profits, government agencies, and foundations. Only a handful (about eight) have carved out time and space for deep and meaningful conversations. Organizations most enamored with the language of innovation (“we just want our staff to be innovative”) find our process most jarring, and of little tangible value. They are right. The products we make (stories, insights, visual scenarios, prototypes) have little tangible value sitting on shelves. Their value comes through wrestling with multiple truths, and co-constructing alternative realities; realities which include organizations ceding power to community. As much as organizations wish they could just purchase a workshop or training, create a toolbox, or build a website to unlock innovation, they are sidestepping the real work to be done: nurturing humility and wisdom.