Categories

Operationalizing values

Agency and control are some of our core values. We think they offer a space where growth and reflection can begin to happen. That’s a really good foundation for most things we’d want to do, like establishing personal aspirations and healthier relationships.

We’ve tried to design our research to be less extractive, and more generative: to give agency and provide validation. However, no two projects are the same. Each time we get on the ground, we have to revise how we build relationships and engage in conversations.

Having a choice

So, how do we maximize people’s sense of agency in the research process? One way we operationalize that value is though offering choice: choice over how you want to be known and represented to others, choice over what you want to talk about, and choice of ways to express yourself.

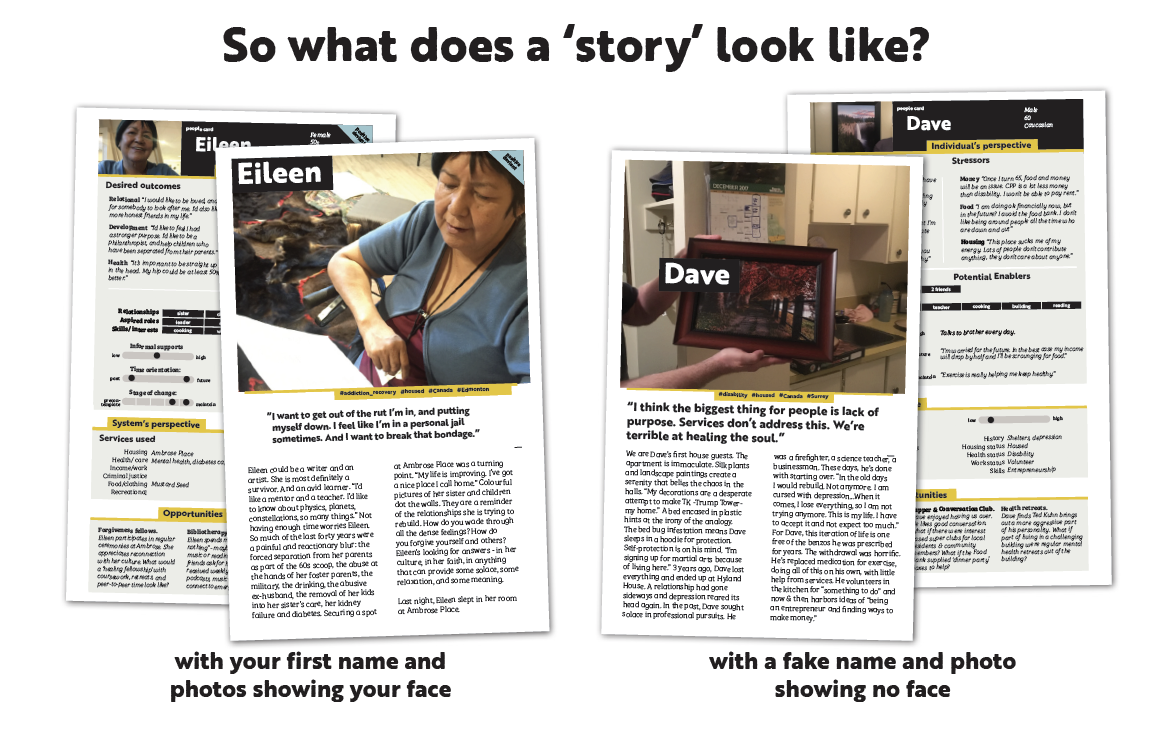

Everyone we spend time with is asked how they would like to be known in our research products. You can be known by your first name alone, or by a pseudonym of your choosing. You can have a photo of your face, or a non-identifying photo, of your hands, you turned away, or of an object that is important to you.

For some, this is an important choice. While marginalized people we spend time with are more acquainted with the option to have confidentiality or anonymity, many find the opportunity to have visibility refreshing, and significant.

Often, organizations have legitimate worries about the context and conditions under which people are making a choice to have their name, face, and story uploaded to the internet, where that story can reside for posterity. Are people with a history of mental illness or addiction or unemployment or [insert perceived vulnerability here] able to weigh the consequences of their choice? This is a live ethical question!

One thing we have observed from past projects: people with active mental health challenges living in their own reality have trended towards being anonymous or have proven tricky to find again. When we are unable to return people’s stories to them, we default to anonymity. That part of our process ensures that people make a decision having seen their story and, something I had not previously considered, that the decision is stretched out over at least a month, from when we meet them to story return.

Tools & touchpoints

A menu of conversational topics

It’s been our standard practice to let people we spend time with know that they have full choice over what we discuss, but, how practically to do that when we’re the ones driving the conversation? In an effort to make our agenda more visible and contestable, we created a menu of conversational topics. We presented it up front so people could flag anything that made them uncomfortable, comment on what they would like to say about a topic, or ask questions.

Our research is not a survey, it’s a two-way conversation, where honouring the relationship between us has to take precedence over the uniformity of data. Because we do design research we are not concerned with evaluating or validating a hypothesis, but rather, in collecting data that reframes our understanding and opens up different insights and opportunities than we perceived before. Understanding what is easy or hard to talk about is good data in and of itself.

Reciprocity

Something we frequently encounter in field work is how people’s identities are shaped by interacting with services in which they are always the subject of questions, and always on the receiving end of help. We see reciprocity as an important dynamic in developing a positive sense of agency: the knowledge that you have something to offer, and that others have a personal need to connect with you.

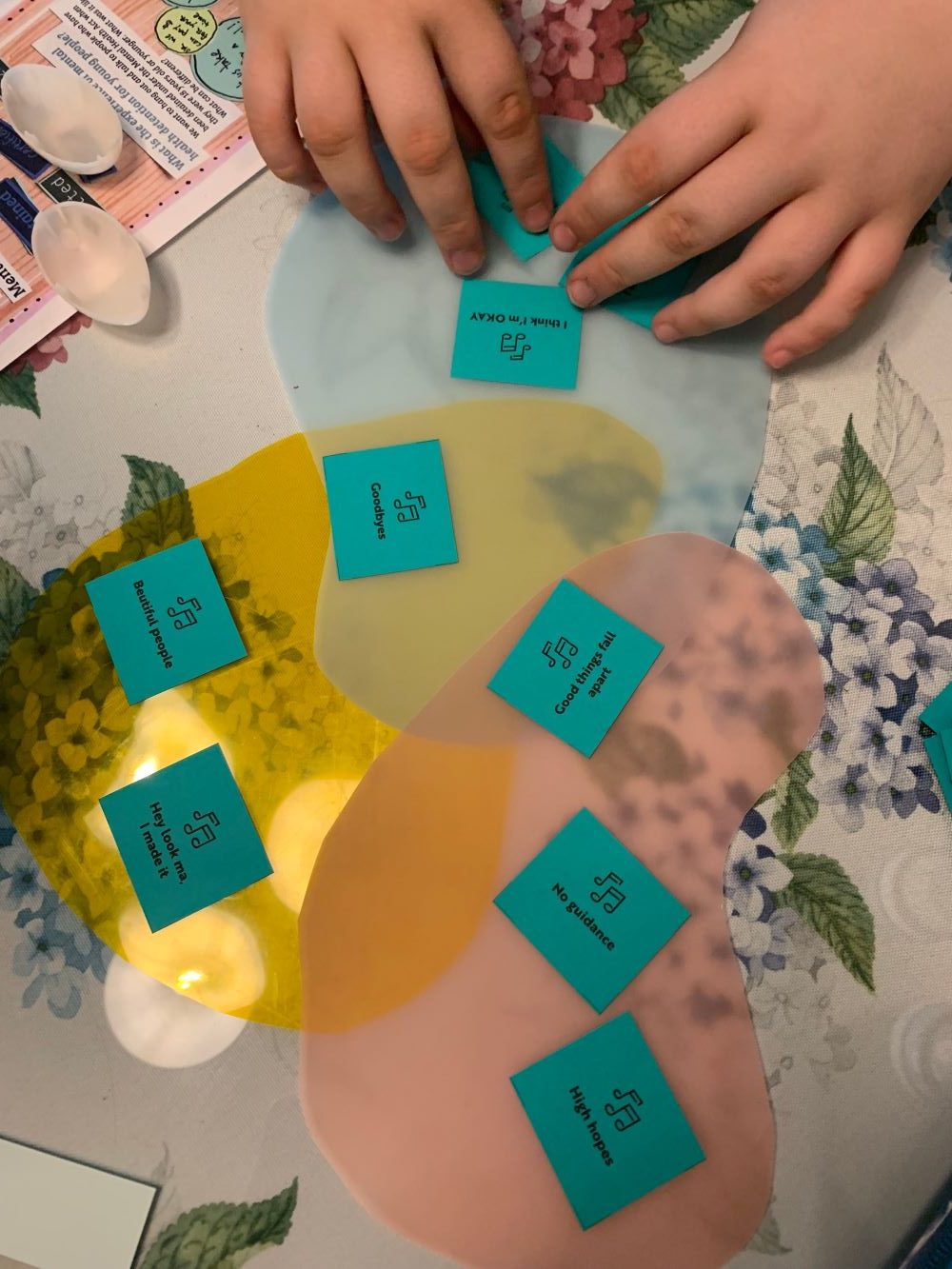

Previously, we often invited people to ask us questions during research. Our team of researchers consider personal disclosures a legitimate part of rapport-building in any human interaction. However, in this piece of work, it became part of the structure. Our designers developed a game that operates a bit like rummy. There are four rounds, with a unique card deck for each round that allow us to delve into values, stressors, self-descriptors, and current life narrative (through song titles!)

We’re all playing the game, all selecting the top cards that describe us, and identifying where we have these elements in common. At the end of each round, we rationalize our card choices, using the opportunity to disclose something about ourselves and where we are at in life. It did not make our life histories any more similar, but it introduced a mutual vulnerability which felt like a small act of solidarity against the backdrop of these youth’s often very isolating experiences.

We also invited youth to participate in creating their own product to share their perspectives and experience more directly. We were overwhelmed by participants’ desire to find other ways to share and tell their stories. At the time of writing, the podcast production has begun, with one ethnographic participant taking on a paid fellowship to help lead the process.

Feelings with fabric

As one youth observed, “nobody’s ever really asked me about my experience with my mental health.” He said it felt good to talk about it, but he sometimes struggled to put words to difficult experiences he had never discussed. Picking up on a strategy that had worked well last February when we explored emotions with newcomers, we brought fabrics back into the fray.

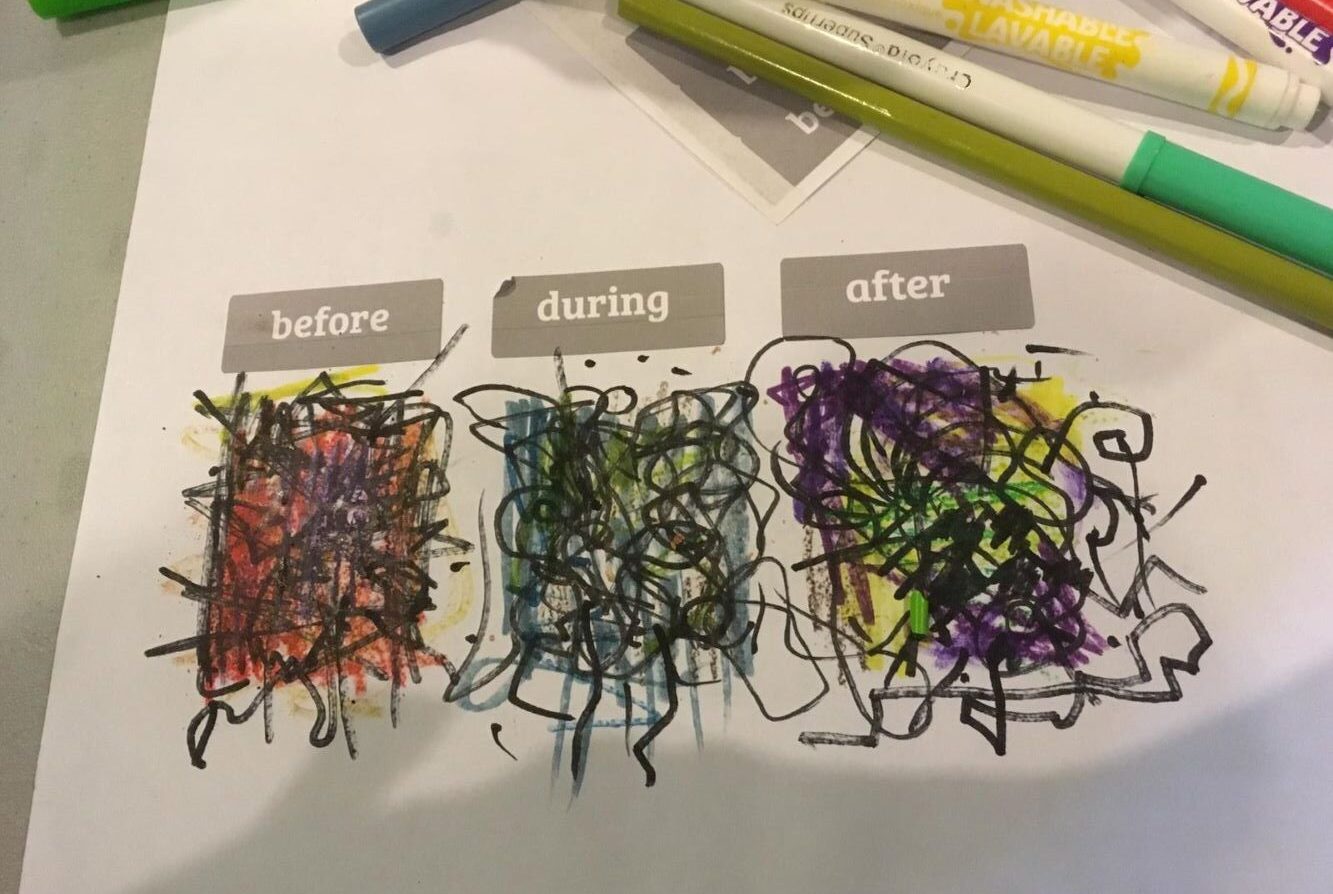

Youth chose swatches of textiles with different colours and feels, to introduce the periods before, during, and after the hospital in an impressionistic way.

From there, they worked backwards to deconstruct their choice of fabric, often by naming some of the pervasive feelings from that period. We heard words like “hazy” and “isolating” and some youth were also able to delve into particular memories, interactions, and environments that helped to produce those feelings. Starting with fabrics allowed us to get at hard-to-express experiences, and latent emotions, (hopefully) without putting words in people’s mouths.

Honouring and validating stories

We have an existing practice of returning people’s stories to them. Composing someone’s story is an honour we endeavour to uphold with some humility. As researchers and writers, we make consequential decisions over what information to highlight and what information to leave out. Our story is about a person’s perspective at a moment in time and offers no conclusions, but plenty to chew on. We return profiles to people so that they may review these decisions, check our assumptions, reflect on themselves and our interaction in that moment, and rewrite story elements.

Ideally, profiles are a kind of therapeutic intervention in and of themselves, providing a sense of closure and validation. In narrative therapy, the story return might be considered an act of “witnessing” whereby the listener acknowledges the impact of the person’s story on them. Our hope is that story collecting and sharing feels meaningful, not transactional.

Upon reading their story, one young person said: “I feel kind of proud that I am still here.” For another young person, reading the story sparked new revelations: “Wow, that’s pretty good. It definitely feels like a lot of stuff I said and want. But there are some updates.” Where we are unable to find or reconnect with people following our time together, we anonymize their story, following the terms of our written consent.

Witnessing

As a team, we see how the powerful moments that come from story return fuel our fire – and our sense of personal accountability. We’re always looking to collapse the gap between system leaders and end users, where possible, to share the privilege we have in spending time with people.

That’s why we’re exploring how system leaders can “bear witness” to the stories they read. What if decision-makers wrote letters to the people behind each story and played back what struck them? How might that help to close the feedback loop?

Our hope is that a letter-writing practice might deepen the impact of these stories for both participants and systems, forging a stronger connection between them. Stay tuned for what this looks like!

Capacity to hear and respond to research

Witnessing is one way we want to tweak how we invite organizations and systems to engage with data. There is a lot more to do on this front. While story return to participants is commonly experienced as rewarding and meaningful by researchers and participants alike, sharing data back to systems offers up some different complexities.

Our research is commissioned by organizations in systems that have their own way of categorizing people’s needs and their own accountabilities. Sometimes the stories we hear raise pain points and opportunities that implicate multiple parts of a system…and may not fall under anyone’s jurisdiction. Reporting back on what matters to people, even where it spills beyond the scope of an organization’s or institution’s current scope of work, is another way to validate people’s experiences and extend their agency. As social design researchers, we want to be the servants of what could be, not what is.

This too requires some iterations in the way we storytell our research and host meaty conversations that wrestle with values and practices. See this month’s long-form blog “Please, Can We Get to the Heart of the Matter” by Sarah for more on this topic. It’s an area in which we feel some of our most profound inadequacies and deepest learning.

Throwing a few more things at the wall

Time will tell which of these iterations has the hoped for impact and sustainability, though some, like our rummy game, have already proved valuable. What matters is that amidst our own looming targets and deadlines, we continue to make time to experiment and test new approaches that tell us something about what it means to shift the social welfare state in a direction that allows for greater human flourishing. Again and again, that demands our own personal growth and investment in all the relationships required to make such an ambitious shift.