Categories

“I’m the most humble person I know” is my style of humour. It’s the kind of paradoxical dad joke I like to tell and then make sure everybody sees what I did there.

I know, it’s comedic gold. But it also represents the complexity of measuring humility. The most humble among us are, by definition, the least likely to boast about it. Why measure humility? Humility is one key to living authentically, being vulnerable, and thereby connecting with fellow humans. The New York Times reached that conclusion last month. But it’s shown up across the world throughout time. The founder of Daoism, Laozi, advocates the importance of embracing differences while practicing the spirit of humility. Being “humble and receptive like the valley” (虛懷若谷xu¯ hua´i ruo` guˇ .) is the pathway to gain true knowledge (Chen 1963 quoted in Chang 2012)”.

In a different time and place, the concept of humility is reflected in Islam. The Qur’an (25:63) says:

((( وَعِبَادُ الرَّحْمَٰنِ الَّذِينَ يَمْشُونَ عَلَى الْأَرْضِ هَوْنًا وَإِذَا خَاطَبَهُمُ الْجَاهِلُونَ قَالُوا سَلَامًا)))

According to Abdullah Yusuf Ali’s translation into English, this means:

“And the servants of (Allah) Most Gracious are those who walk on the earth in humility, and when the ignorant address them, they say, “Peace!”

In both examples, there’s a tie between knowledge and humility. We think this widely-recognized concept is a worthy perspective to apply across cultures. So did the folks who named cultural humility.

Cultural Humility

The first definition of cultural humility in academic literature states that it “incorporates a lifelong commitment to self-evaluation and self-critique, to redressing the power imbalances in the patient-physician dynamic, and to developing mutually beneficial and non-paternalistic clinical and advocacy partnerships with communities on behalf of individuals and defined populations” (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia 1998). More simply put, cultural humility is a commitment to a lifelong journey of learning about others and reflecting on one’s position and power.

As a topic of study, it’s been around for about 20 years. It originated in the field of training medical professionals. Healthcare and the question of one’s bodily autonomy are culturally sensitive environments. Given most doctors have a whole lot more relative power than most of their patients, it’s vital that they value cultural humility in dealing with patients.

It’s also been applied in the field of social work. Maybe you’re familiar with its relatively more popular concept cousin, ‘cultural competency.’ Fisher-Borne (2014) succinctly outlines the distinctions between cultural competence and cultural humility. The main critiques of cultural competency are that it focuses on knowledge acquisition and thus suggests an endpoint of knowledge; it doesn’t inherently address issues of social justice; and it can lead to stereotyping the ‘other’. Cultural humility, conversely, recognizes that people have layers of complex identities. It recognizes that learning how to work with people is a lifelong and ongoing process. This process isn’t just about learning about others, but about understanding ourselves and reflecting on and challenging power imbalances.

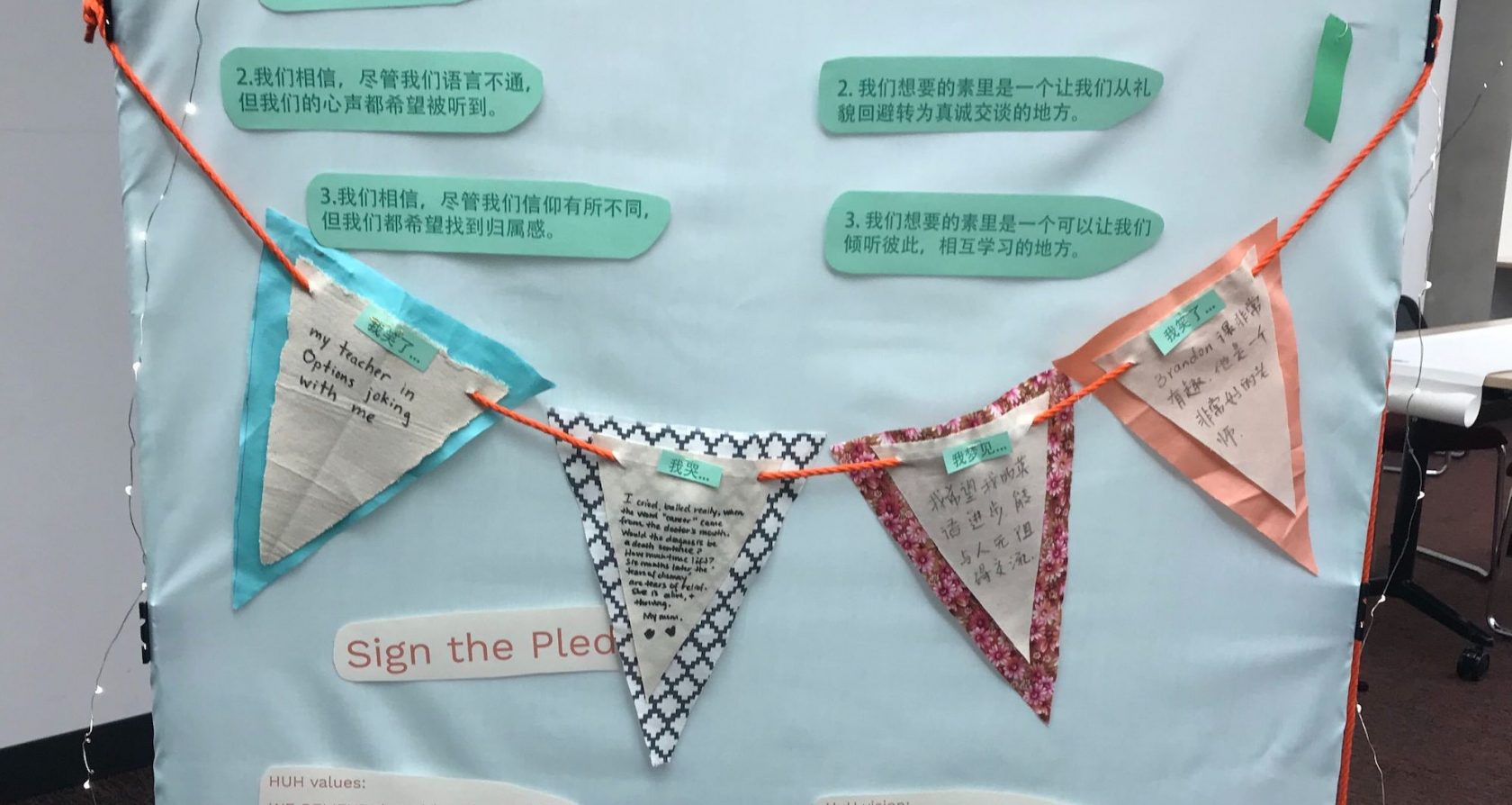

On the ground with newcomer seniors and newcomers with disabilities in Surrey, we found a lack of opportunities to engage with people from outside one’s culture and language group. Newcomers enjoyed engaging with us because it was a rare chance to ask, to learn, and to connect with someone different. We had moments of reciprocal curiosity-sharing, discussing personal questions about our families and our funeral traditions, for example.

Both sides learned a lot about one another, and through examples, identified what the society each of us grew up in defined as “normal”. We don’t let these interactions lead to assumptions that everyone from a given country or culture has homogenous values, beliefs, or actions. We learned particularities about whichever human we were engaging with. I would say the biggest piece of learning, though, wasn’t a trivial tidbit about “the way things are done here vs. there”. The biggest learning was: Huh. We don’t even know where to begin to unpack the complexities of one person. And we’ll never know all the complexities. Instead of trying to learn all the things and striving for some impossible place of all-knowing ‘competence’ about a cultural group, we’re using cultural humility as a bouncing off point for non-stop listening, learning, and understanding.

Making Real

So, how does one utilize this concept that would be a swell way for everyone to relate to everyone else? Is it through diversity training? We researched some available diversity training out there, and a lot of it stays in the very theoretical and general realm. Respect others, check. Position yourself within society and acknowledge your power and privilege – double check. This is all valuable knowledge to have. But how can this knowledge live beyond a powerpoint or a one-day training, and show up in the learner’s everyday practice?

Cultural humility is not a training checkbox to be marked. It’s a value. We’re not trying to inculcate such values – that’s not how this works, we think. We are trying an approach informed by experiential and in-context learning pedagogies. In other words, people need the opportunity to practice a thing to effectively do that thing. Cultural humility is a mindset, and we’re asking folks to engage with it by practicing the necessary skills. We’re not going for the training, it’s the practice. It’s the in-person learning that you can only get by breaking down the barrier and just plain talking. Ask whatever questions you have about another person, and share whatever answers you have about yourself. You’ll be delighted you did. You may also feel quite awkward, but at least you would have learned something.

We’re hoping this experiential learning happens for all parties involved. For newcomers, it’s a chance to practice English and/or using language translation tools, expand their networks, or just have something to do. After all, everyone wants to feel part of something larger than ourselves.

Let the record show our recommendation is not to spiral about how you don’t know anything. That’s not too productive for anybody. We’re asking folks to be bold in their curiosity and bold by reaching across boundaries that usually seem out of reach. As you’re listening for the answers to your questions, though, you must listen from a stance of curiosity over judgment, every single time. Be humble about what you don’t know, and vulnerable enough to admit it. And you must ask yourself why your gut reactions told you something. As it turns out, prototyping is a similar balance of boldness and humility. We must exhibit boldness enough to capture imaginations, and bring people on the journey of believability that this idea just might work. At the same time, we have to be humble enough to know that it’s a work in progress, and that we will only build (and take apart, and rebuild) this idea with a whole lot of feedback.

So…*ahem* back to measuring cultural humility

As you can see, one’s journey of cultural humility is deeply personal and complex. Turns out anything involving one or more humans usually is. Juarez et al. (2006) attempted to develop curriculum in teaching and measuring resident medical students’ cultural humility. Secret-shopper style simulated patients rated that the residents were more attentive to the patient’s perspective and social context and rated them as having improved cultural humility. That’s one way to measure it. But in self-reporting, the students marked themselves as having no improvement. That probably means they’re more open to admitting they don’t know what they don’t know, which, ironically, is the point of learning cultural humility. We’ll continue to develop and test these ways of measuring, and we’d love to hear any suggestions! I guess nobody wants to be that human who claims to be the most culturally humble person they know.

Citations

Carey, Benedict. “Be Humble, and Proudly, Psychologists Say.” The New York Times, 21 Oct. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/10/21/health/psychology-humility-pride-behavior.html.

Chang, E-Shien, et al. “Integrating Cultural Humility into Health Care Professional Education and Training.” Advances in Health Sciences Education, vol. 17, no. 2, 2010, pp. 269–278., doi:10.1007/s10459-010-9264-1.

Chen, W.T. A source book in Chinese philosophy. 1962. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Fisher-Borne, Marcie, et al. “From Mastery to Accountability: Cultural Humility as an Alternative to Cultural Competence.” Social Work Education, vol. 34, no. 2, 2014, pp. 165–181., doi:10.1080/02615479.2014.977244.

Juarez, Jennifer Anderson, et al. “Bridging the Gap: A Curriculum to Teach Residents Cultural Humility.” Family Medicine, vol. 38, no. 2, 2006, pp. 97–102.

Tervalon, Melanie, and Jann Murray-García. “Cultural Humility Versus Cultural Competence: A Critical Distinction in Defining Physician Training Outcomes in Multicultural Education.” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, vol. 9, no. 2, 1998, pp. 117–125., doi:10.1353/hpu.2010.0233.

The Qur’an 25:63 (Translated by Abdullah Yusuf Ali)