Categories

Structure versus discovery

‘How much structure is needed to support newcomers to test new business ideas at neighbourhood events?’ That’s a key question for Night Life, an idea to support newcomers to test out and develop business ideas by hosting neighbourhood events. Grounded Space lives in the land of emergent processes, where we may know where we’d like to go but not exactly how to get there. This style of process can be fruitful but difficult to navigate. The structure of team roles, who makes decisions, and who we are accountable to are usually unclear and changing. We aim to give our end users agency in our process while still holding our vision for shifting the status quo. With a big tension being that I said our two times in that last sentence. If we are to democratize design, and truly design with people how do we bring them inside our structure, and alongside towards a next practice future.

At our Surrey Concept Kickoff event some of our community stakeholders presented polarizing opinions of structure. From the world of finance and from a Design School perspective we heard structure would be beneficial because 1. It would assure people know where in the process they are, and 2. funders are able to be confident that the businesses are on pathways to success. A contrary view from the world of change-making urged us to embrace a lack of structure — to leave it open to newcomers who we would be working with to set the structure as it makes sense for them — instead of imposing our own structures on them. This interaction really highlighted the tensions I feel between my education at design school, and how I see many design organizations working, and the way that we aim to work to empower and elevate newcomers.

Adapting design from its business world roots

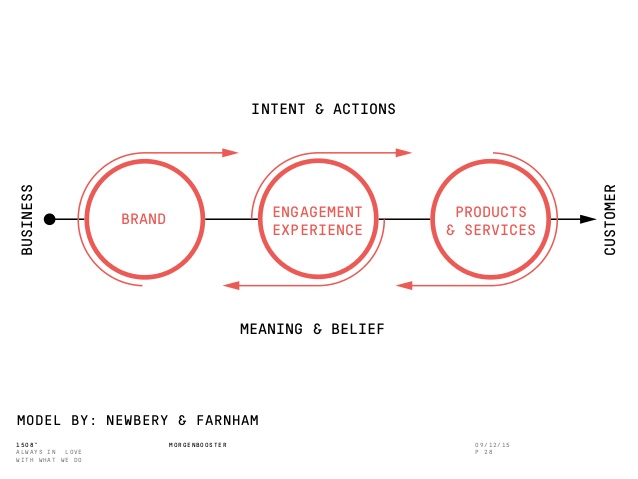

In school I was told it was the job of a designer to be able to research their intended audience, hear their pain points, understand the business case, and find a solution to both by gathering insights and building a product, platform or service that people didn’t even know they wanted. That worldview of design fits into the traditional structure of businesses with customers and designers with deadlines. Alternatively a project like Kudoz flips the script, engaging designer, coaches, and community members to work together to create meaning and value for the intended users of the project.

To go from thinking of the world as dollars and clicks to people and stories really changes how I think about team structures and decision making. School taught us – and rightly so – that designers shouldn’t play the role of the expert. In this world of ethnography, deep dives and grounded change, serious questions arise around who the experts are. Our team has been listening to newcomers, and developing a viewpoint on the issues since this work started in November. Our team is also rich with views on behavioural theory, and what our ideas need to have to create the future we want to see.

Who makes decisions?

If members of our team hold expertise and we all try and listen to the people we’re trying to reach, what is the right order of operations in decision making? We tested out a new structure to make a decision on what idea to prototype and which ones to leave behind. This lead us to consider factors of systems change, market factors, and idea champions among newcomers themselves. In the end we ended up not choosing Night Life – the idea that was most favoured by the people we co-designed with.

I do believe that the choices we made under our decision making framework will ultimately lead to a more successful prototype and future services. But because this structure only emerged after our co-design sessions we were not able to share during sessions how we would be honouring their feedback and knowledge. There is always a question in my mind about how far to pull back the curtain in a co-design session. If we try and explain the origins of IWF, all of the steps that took us here, and why we hold the values and opinions about today’s social services landscape we would likely take up a lot of space and time. But when we don’t lay out the core of why we are doing this design work — to strengthen informal support, to create purpose and relationships, and to stay responsive to end users — do we limit the possibilities for a deeper partnership with co-design participants?

From rubrics to insights that bubble unbidden

This gets me back to this underlying tension, between the predetermined rubrics, grading structures, and lesson plans, of which school was made up, and the ability for our process to emerge over time and for insights to bubble up. A standard organisational structure of timelines, checkboxes, and results would make it very easy to tell our community partners, co-design participants, organization co-workers what it is we are doing and where we are going, but we risk missing out on going to the greenest pasture, and sparking new innovations. While our emergent process allows us to adapt to information as we hear it, and drive our projects to jump into the next practice – it also leaves our work more vulnerable to a smaller set of personal biases, and the worldview of the team shaping what we design.

As we tried this week, a mix between carte blanche for us, or passing off decisions to potential end users entirely, may be the right call sometimes. One of the considerations that swayed our decision was not the expressed needs of newcomers but the latent needs that kept popping up through repeated interactions. These are the anxieties and fears that, if unattended to, might still get in the way of full engagement with an offering like Night Life. We consider it our responsibility not just to please end users but to create the conditions for growth. Though we reached a decision about what concept to prototype, we recognize that creating structural conditions to support deeper newcomer involvement while still in the early stages will be crucial to push out own growth forward and find a sweet spot between what people want and what they need.