Categories

Loss of agency and control is a common denominator of every wicked social problem we face. Homelessness, addiction, social isolation, stigma, displacement, migration, domestic violence, family breakdown, etc. rob people of their most precious freedoms. They install fear and instill shame. They corrode trust and contort identity.

Regaining agency and control is a common denominator of all personal and social change. Finding safety, solidarity, voice, dignity, meaning and purpose is at the heart of individual and collective healing.

We live as if power were a zero sum game. Even our democratic political systems treat power as a finite resource. As elections in Canada, the US and the UK loom, candidates scamper to engage the every day person at every day places from backyard bbqs to businesses, farms to front doors. We are told — in tweets and memes, emails and stories, posts and clips — that “we, the people” have power: the power to donate money, the power to persuade our friends to donate money, and the power to allocate our power to a political party or person.

A few Saturdays ago, on the second floor living room of a rental house tucked behind a mosque in South Surrey, Abdul’s family graciously greeted us. They didn’t know anyone when they arrived in Canada, eight months ago, from Syria via Jordan. On this afternoon, they gathered a group of former teachers, lawyers, mechanics and entrepreneurs for cardamom coffee, dates, pizza, coke, tea and Roz bi-Haleen Mbattan (rice pudding with pistachios). We brought five half-baked ideas. Four hours later, we had more than doubled our idea yield — with concepts for political philosophy dinners, industry English language learning, farm home stays, entrepreneurial bazaars, and welcome tours.

But, how to systematically materialize this creativity? How to recognize and support leadership amongst families and friends? That, we’ve not meaningfully figured out. And despite the rhetoric of empathy and inclusivity, human-centered design doesn’t yet hold the answer.

The promise and perils of design

What first attracted me to human-centred design was its generative versus distributive approach to power. Fellowships on Capitol Hill, in Westminster, and at the Beehive left me questioning where new ideas come from. So many policy proposals were recycled from other jurisdictions, lobbyists or academic think tanks. I saw little imprint from every day people — beyond consultations, largely conducted as obligatory exercises after key decisions had been made. Community development work with cities, schools and nonprofits engaged every day folks along the way, but the focus on consensus squeezed out the most novel ideas, catering to the average, not the most marginalized. Where policy was so often limited by regurgitated analytic frameworks, community development was so often limited by what every day people had seen, heard or could imagine. Without fresh sources of intelligence and ideas, both top-down and bottom-up problem-solving approaches reinvented versions of the status quo.

Design seemed to offer a distinct path forward. It promised to reshuffle the decision-making sequence and bring fresh intelligence and ideas into the fold. Research with people, in their own contexts, gave voice to the extremes, reframing abstract problems from the perspective of those with direct experience. Inspiration from lateral fields widened people’s points of reference and choice. Visual prompts and emotive storytelling brought out imagination and play. Beta-testing and prototyping facilitated fast learning. Design, by the looks of it, could cut through circuitous conversation and lengthy upfront planning — not through consensus or authority — but creative action.

For a while, creative action produced surprising results. Families who told social workers to “fuck off” opened up to us. Women in domestic violence shelters imagined alternative supports. Youth disengaging from school turned up to give a new service a go. But, after the research, workshops and prototypes ended, where did the generative power go?

Too often, nowhere.

The dominant business model of design positions it as a tool for paying clients. Paying clients cede some creative control to the designer — who, far from serving as a neutral facilitator, interprets and filters intelligence and ideas. What happens with their pretty products — the personas, wireframes, mock-ups and blueprints — typically lies outside the scope of the contract. Implementation, where one-off processes give way to sustained structures and relationships, is for somebody else to figure out. But, who and how?

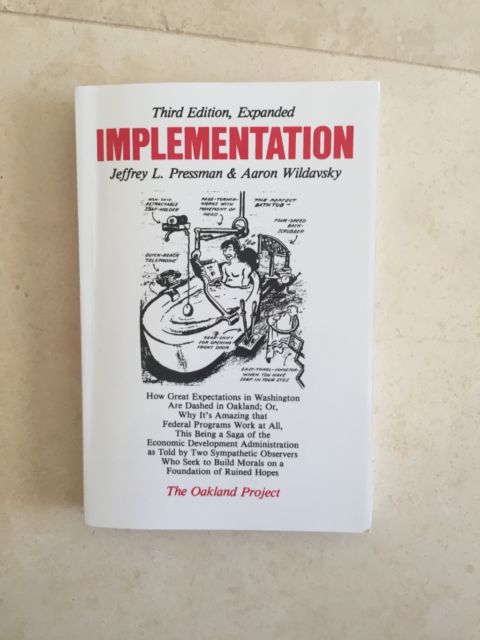

A book with a very long title exposes the long and convoluted path between intent, ideas, implementation, and change. Implementation: How Great Expectations in Washington are Dashed in Oakland; or Why, It’s Amazing that Federal Programs Work at All, This Being a Saga of the Economic Development Administration as Told by Two Sympathetic Observers Who Seek to Build Morals on a Foundation spurs a serious reality check. Four years after a big policy passed, with big money attached, jobs for the long-term unemployed had not materialized, while handsomely paid work for civil servants, project managers and professionals did.

Awareness of the implementation chasm has not made it easier to rebalance power.

When InWithForward came to Canada five years ago, we started with the implementors: the social service organizations receiving large government contracts to deliver services to marginalized citizens. Rather than treat organizations as our paying client, we set out to form long-term partnerships, with ambitions to move ideas into executed form. We’ve established four long-term partnerships, resulting in two implemented models (Real Talk and Kudoz), and two ideas in the prototyping stage (Meraki + The Concept Collection). While these models and prototypes create new programmatic roles for end users, the partnership structure ultimately retains control. Money flows to us. Accountability sits with us. Management falls to us.

Five lines of inquiry

That’s leading us to inquire:

- Are our design teams becoming just another professional class: holding versus sharing power?

- What does sharing power really look like in discrete moments versus repeated engagements?

- What are alternatives to consensus-driven structures?

- Are we asking too much or too little of people?

- What happens when people have limited (or no) experience of shared power? When is having ‘no opinion’ suitable? And when is it reinforcing patterns of exclusion and marginalization?

These kinds of questions won’t be solved with an inclusive design toolkit or card deck. When a recently arrived Iraqi refugee asks us if she will get in trouble for sharing how unwelcoming she found the official welcome centre, and despite assurances of her safety, doesn’t want to leave her phone number, it’s apparent how deep embedded scripts of powerlessness run. When we — as a majority secular, educated, middle-class and white team — ask about people’s emotional experiences in Canada, no amount of clever exercises can circumvent cultural norms and expectations about what is “polite” and “appropriate” to say. Yes, we can be explicit about our differences (and similarities). Yes, we can acknowledge the power dynamics. Yes, we can try and socially re-norm a range of responses. But little of that is about method. Much of it’s about leaning into vulnerability, humility, discomfort, and patience. All of which requires us to show up to interactions in a more upfront, and less gimmicky way. We like to say we don’t have an agenda: that our agenda is set by the people we’re with, but that, I’ve learned, is disingenuous. We do have an agenda: to be with people, to connect with them, to learn from them, and where possible, to collaborate with them.

Collaboration takes time. More than a year after meeting Mary Jo at a night college and hearing her newcomer story during an ethnography, she’s joined our North York Community House team in a paid role. For the first months on the team, she wasn’t so sure about her place. She apologized for her opinions. We, too, felt self-conscious. Were we asking the wrong questions? Were we overly steering the conversation? Were we too heavy handed? Somewhere along the way, six or seven months in, the awkwardness faded. Mary Jo took the baton and ran with it: outpacing everyone else on the team: mobilizing her kids, family members, and extended network to co-design and build ideas with her.

Sure, peer workers aren’t a new concept. But, how to empower without professionalizing? In other social sectors, there can be a tendency to turn peer workers into para-professionals: to train them in best practices, bring them in line with system protocols and rules, add them to committees as “the” representative of their community, and put them within the reporting hierarchy. We’re trying to figure out how to forge a different kind of relational basis as creative partners.

Of course, not everyone wants to be a creative partner. How might we design a range of roles, attached to our structures and not just our processes so people like Abdul can, like Mary Jo, take the baton and pass it along to community members? For that to happen, we must get real and explicit about how power is expressed in small and big interactions, organizational models, governance, and all.

Author Eric Lieu, in an interview for Democracy: The Journal of Ideas, offers some guidance …

“The goal here is to show people how to get literate in power. But that literacy in power isn’t just to make us awesome tacticians. There has to be some deeper sense of why. Power plus character equals citizenship. And I don’t just mean individual character, but collective … Once you’ve taken stock of your power you have a very simple choice. Are you going to hoard or are you going to circulate it?”