Categories

Wait, What is Co-Design?

What’s the best way to go about designing supports with the people who use those supports? We have a few hunches, but the truth is, it’s complicated. Our aim is to design something that appeals to newcomers while also taking them on a journey to consider different ways of engaging with emotions. We’re trying to envision the future and share in a vision with people while respecting the integrity of cultures-of-origin and the past.

Co-design is the way we’re trying to reach that aim, but it’s not as simple as it may seem. Co-design is a design method based on the premise that there is no one better to decide what supports newcomers need than newcomers themselves.

Design tells us people can better express preferences if they are responding to a tangible provocation. We don’t just ask newcomers to create from scratch a service that would address their problems. So, to develop ideas and visual prompts, we spent time with newcomers to build relationships and understand their lives in context. The process oftentimes leads to more questions instead of more answers. Although we enter our engagements with people with specific research questions in mind, we leave with a lot of data about the success of the co-design interaction itself.

What Co-Design is not: a Panacea for Sharing Power

In recent years, the field of welfare planning has made more effort to include people with lived experience in the design of programs. It’s an improvement over excluding people from their own decision-making processes. And yet, there’s a danger in assuming that incorporating people into idea design is necessarily “doing it right.” It’s easy to gloss over the multitude of complications that are wrapped up in co-design. For instance, maybe the user finds it exhausting to participate, or maybe they’re being asked to set aside their own best interests in order to consider the greater good of society (Cribb & GeWirtz 2012). These complications must always be kept in mind, along with the aim of making decisions in an equitable way and sharing power.

Power isn’t some quantifiable unit that can be split 50/50. First, our positionality means we wield power in ways beyond our control. As a trained human geographer, I think about how my fixed or culturally ascribed attributes (race, class, gender) situate me in the world and next to people I co-design with. I also think about life experiences that I have or have not had as a lens through which I view the world; it’s impossible to divorce myself from, well, myself. (Chiseri-Strater, 1996; Milner 2007). I know I can’t extricate myself or the people I’m co-designing with from these webs of power and authority. I don’t know if people respond to our invitations to co-design out of a sense of coercion, genuine desire, or both until we’ve developed a stronger relational basis with them.

What does this mean for us? It means not to make assumptions. Our positions of power, relative to one another, don’t mean we know more or less about what settlement supports are best for newcomers. It means it’s something to consider before we enter the room, in the design of the process. It’s something to acknowledge throughout building relationships. And it’s something to keep at the core of our interactions, asking ourselves: How do I make myself vulnerable so that my positional power can be questioned, reinterpreted, and eventually appropriated by those we interact with?

There’s no easy answer to this. “Shared power” isn’t a status to be achieved – it’s a constant consideration of each moment of every interaction. It’s a stance of humility and a commitment to iteration. There’s no such thing as reaching a final destination of power balance, because it’s constantly being negotiated with each exchange. Instead of trying to examine an entire relationship with a co-designer, I’m zooming in to deconstruct one single moment with someone who has informed our work greatly. Abdul (pseudonym) was a lawyer in Syria. He and his lovely family graciously hosted an idea party, or co-design session, with us and their friends.

Roles, Props, Script, Settings

We break down interactions into 4 components: roles, props, scripts, and settings. To set the scene, I’ll show you these components in Abdul’s context. I’ll also highlight the questions I grapple with in each.

Roles:

There were many roles being played simultaneously: Abdul was the host to me and his friends; the father to some boisterous youngsters; a consultant on the prototype. I was the guest and the facilitator. The third and most crucial role was that of interpreter, a member of our team who mediates our interaction. Grappling questions: Does this person really want the role they’re taking on or are they just being polite? Is this the first time since coming to Canada somebody has asked Abdul to give significant input? How do I aid people to take on this role without leading them or asserting power over them?

Props:

The designers on the team are particularly concerned with our props. Abdul had food to offer, I had a box with cards to prompt conversation. Grappling questions: Do these written materials alienate people who may be less comfortable with text? Does Abdul have more power in this interaction if he’s writing, or would I be forcing that onto him? How do these props encourage or discourage Abdul to interact and share his opinion?

Script:

This includes the order of events, the content of what we say, and how we say things. We have a frame and general idea of how these sessions will go, or so we think. Ultimately, the flow of the session is up to the co-designers. Grappling questions: What culturally-specific scripts am I missing, and how can I acknowledge and respect that? How much do I let Abdul lead the conversation if it isn’t about co-design?

Setting:

in their home. We want to meet people in context. Grappling questions: How does this setting enhance or decrease power imbalances? Does Abdul feel more or less comfortable sharing an honest opinion with me in his home than elsewhere? How does the act of providing criticism jive with how he understands his role as host?

Climbing the Ladder

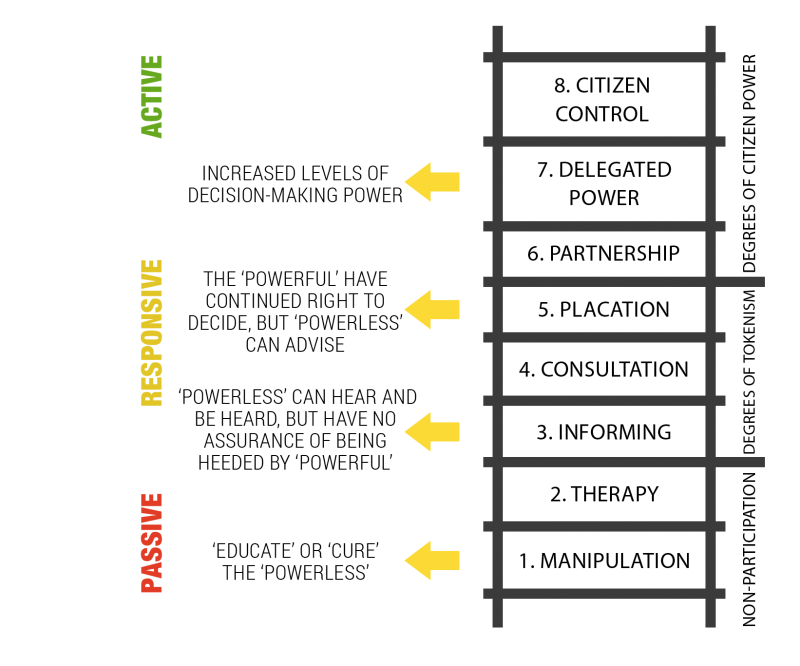

A simple tool to examine this not-so-simple process is Sherry Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation. It’s not meant to categorize entire relationships with people. Undoubtedly, it glosses over the layered complexities of co-design. For a more in-depth critical read of this tool, check out Carpentier (2016). Nonetheless, we used this ladder to consider single moments in co-design sessions to ask ourselves: if we mapped it, what level of participation are we getting to? What level are we aiming for?

Settlement services traditionally exist at level 3: They’re informing people of the services that are available. Surveys and outcome measurement tools attempt to get to level 4, consultation. Limited levels of participation are designed that way – traditional programming does not have wiggle room to be adjusted based on what the user wants after it’s been set in motion. Our process, conversely, is distinct in that it’s meant to be malleable. I believe the highest level that co-design can reach is level 7: delegated power, because if we relinquish all power, it is no longer a project informed by our social scientist and designer expertise. Ultimately, the goal is not to attain a static 50/50 partnership (that I argue can never exist), but to strive for an imperfect but true creative partnership, where all parties have the freedom to build and construct together.

Abdul’s Moment: Bringing Forth Another Idea

When I apply this ladder to moments of co-design, I think of an instance I would categorize as level 6, partnership. By Arnstein’s definition, partnership means power is redistributed through negotiation between parties, who agree to share decision-making responsibilities.

While diving into the Nightlife idea box, Abdul posed to his friends and me: “What if newcomers were connected with senior care homes, so that they could practice their English and provide companionship to elderly folks?”

Designers planned for this moment, to go off-script and riff. The social scientist in me asked myself: what elements of this idea excite Abdul the most? I said to Abdul, “Let’s talk about that idea in more detail.”

At first, Abdul thought my response was at level 5: placation. Due to language woes, he thought I said, “that’s a good idea, but let’s go back to the co-design materials I brought.” He nodded as if to agree to brush past his thought, when I realized there was a misunderstanding. I clarified: “No, let’s talk about your idea in more detail.”

Abdul was surprised to learn that I was attempting to reach level 6: partnership. I asked, “What support would you need to make that happen? What role could you play in the community to facilitate that happening? Would you want Arabic/English interpreters with you?”

We built on each other’s ideas for a few minutes before Abdul’s friend re-directed the conversation. “It wouldn’t work – people in senior care homes would tire easily and wouldn’t be patient with your English.” Abdul and I both felt in that moment that co-design means letting your sense of power deflate sometimes. Maybe we failed to explain to Abdul’s friend that while consultation is about saying yes or no, creative partnerships are about imagining what ifs – together.

Citations:

Arnstein, Sherry R. (1969). ‘A Ladder Of Citizen Participation’, Journal of the American

Planning Association, 35: 4, 216 — 224. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

Carpentier, N. (2016). Beyond the Ladder of Participation: An Analytical Toolkit for the

Critical Analysis of Participatory Media Processes, Javnost – The Public, 23:1, 70-88, DOI: 10.1080/13183222.2016.1149760 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13183222.2016.1149760?src=recsys

Chiseri-Strater, E. (1996). Turning in upon ourselves: positionality, subjectivity and reflexivity

in case study and ethnographic research. Ethics and Representation in Qualitative Studies of Literacy. P. Mortenson and G. E. Kirsch. Illinois, National Council of Teachers of English: 115-132., https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED400543.pdf

Cribb, A. & Sharon Gewirtz. (2012). New welfare ethics and the remaking of moral identities

in an era of user involvement, Globalisation, Societies and Education, 10:4,507-517, DOI: 10.1080/14767724.2012.735155.

Milner IV, H.R. (2007). Race, Culture, and Researcher Positionality: Working Through

Dangers Seen, Unseen, and Unforeseen. Educational Researcher; 36; 388. DOI: 10.3102/0013189X07309471