Categories

Two of these 26 prototypes — and maybe now a third — have had some real legs. That means, they aren’t just a learning exercise; they exist and are impacting actual lives. So we’ve got an 11% hit rate. Pharmaceutical R&D averages a 4.9% success rate from initial research to market approval. So, if we’re doing better than US Big Pharma – on a shoestring budget ($2 million from 2014-18 versus $71 billion in 2016) – shouldn’t we be happy? Aren’t we just expecting too much, too fast?

Probably. The question is whether we’re building capacity for the right things.

Most of the ideas that emanate from our R&D processes are not game changers. And that’s ok. What’s less ok is when ideas perpetuate tired assumptions and reinforce outdated social theory. Sure, we can set criteria, offer feedback, and introduce fresh reference points. But, the more we push for ideas with logics counterintuitive to prevailing systems, the more we reduce the likelihood of organizations steeped within the existing system implementing those ideas.

Over the past year, we’ve come to see our emphasis on organizational capacity as unduly limiting. One tired assumption is that organizations and the services they provide are the best levers for shifting outcomes. Really, relationships are the levers for change. Krazy was recently released from prison, and self-medicates to stay awake and safe. Government services haven’t always worked for Krazy – he’s frequently escorted out of offices, his frustrations rubbing against their customer service protocols.

But, he has struck up a rapport with a local housing worker, who has been able to advocate with government services on Krazy’s behalf. That relationship has smoothed the way for benefits to flow. Whether he is able to use his benefits to rent a basement apartment will come down to his relationship with the potential landlord. It’s his relationship with his friend group which will likely shape his motivation and opportunity to stay on the right side of the law. And it’s repairing his relationship with his estranged daughter that just might influence his future outlook and behaviors.

Most innovations won’t get to this deep level. A new information signposting app, a multi-service hub, or a system navigator role (the three types of innovations we see brainstormed most frequently) are just another set of technocratic interventions. In and of themselves, they don’t create moments of shared understanding, vulnerability, authenticity, or well, humaneness. Sure, new products and new services can be instruments for change, but it’s far less about ‘the things’ and far more about how the things are used, by whom, for what ends.

When we myopically focus on innovations, we fall into a false binary of problem and solution. We miss out on the values and interactions which give a problem form, or a solution shape. We scale the wrong element. Of course, we can’t spread new values and interactions without some sort of vehicle. If we want to influence the relationship between Krazy and his landlord, the vehicle might be some new form of rental contract, or some new property management intermediary, or … But, in the absence of really understanding the values and interactions we’re seeking to unlock, we can easily create a contract or intermediary that perpetuates the same-old, same-old.

And that’s what we’ve seen – despite trying different ways to build capacity within organizations, we’ve not managed to consistently direct that capacity towards new logics. And while we find staff willing to go through a capacity building process, we haven’t found enough folks willing to dedicate their time and energy to implementing what emerges.

Here’s some of what we’ve tried:

- Coaching teams of frontline workers & managers between agencies over 6 months, 1 day week, to develop solutions (what we called Fifth Space)

- Coaching frontline workers to make small practice changes over 6 weeks

- Coaching teams of frontline workers & managers within agencies over 12 months, in concentrated sprints, to develop next practices & identify the culture to embed those practices

Where we have progressed from ideation to implementation, we’ve found staff with entrepreneurial grit willing to take ownership. And we’ve moved beyond organizational boundaries – to involve a much wider range of stakeholders, mobilizing new constituencies and creating some operational distance from the incumbents.

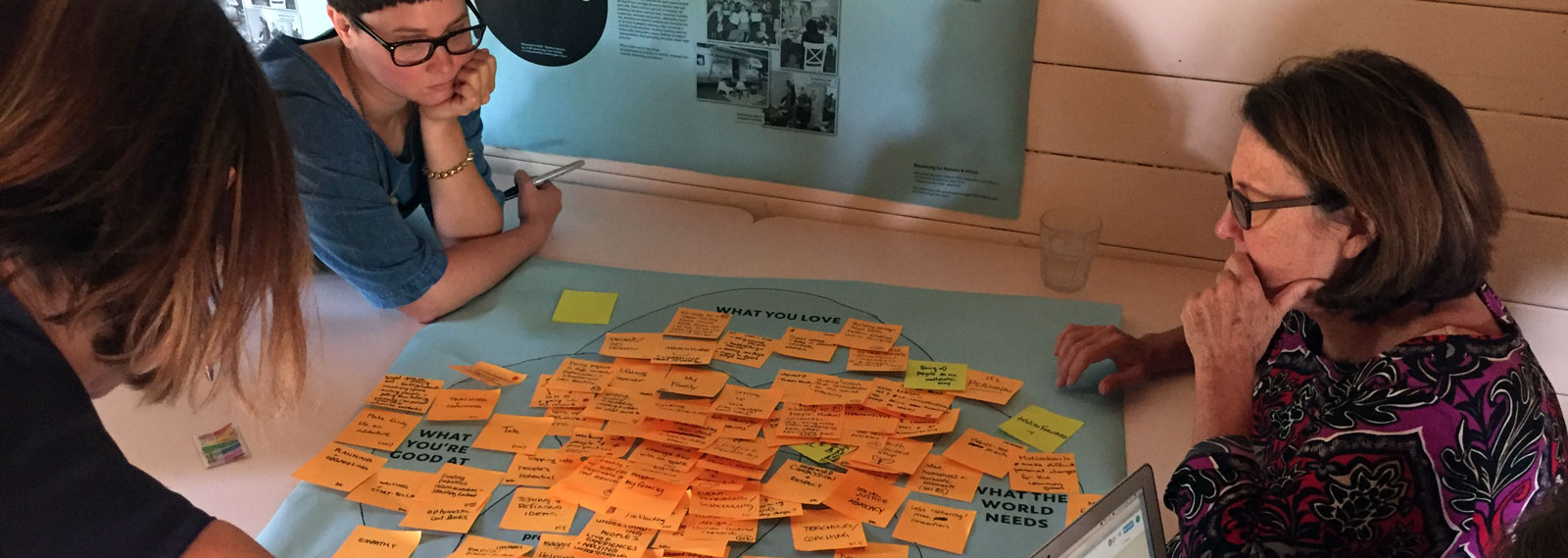

So this year, as we’ve teased in prior blog posts, we’re iterating our capacity building practice. We’re calling it Grounded Space 2.0. Our focus will no longer be on increasing organizational capacity – but instead finding and mobilizing community resource.

Mobilizing community resource to co-create next practice that

- Draws on and develops all of our capabilities

- Awakens our sense of joy, awe, curiosity, appreciation, compassion, forgiveness

- Forges honest relationships where we feel honored, heard, enabled

- Grows our sense of rootedness & expands our sense of possibility

- Re-engages us with purpose

We see organizations as a critical community resource, alongside convenience store owners, pharmacists, faith groups, families, neighbors, etc. Recognizing that the architects of the current systems are unlikely to deconstruct those same systems, we’ll seek out a wider range of collaborators.

And we hope to be clearer about what we’re directing our collective energy towards: re-imagining roles and relationships between people and between people and place. In doing so, we’re seeking to create more moments of beauty, joy, gratitude, forgiveness, fortuity, connection, love, and awe. Because when it comes right down to it – a flourishing life, a life undergirded by trampolines – is made up of a series of moments. Not just innovative products or services.