Categories

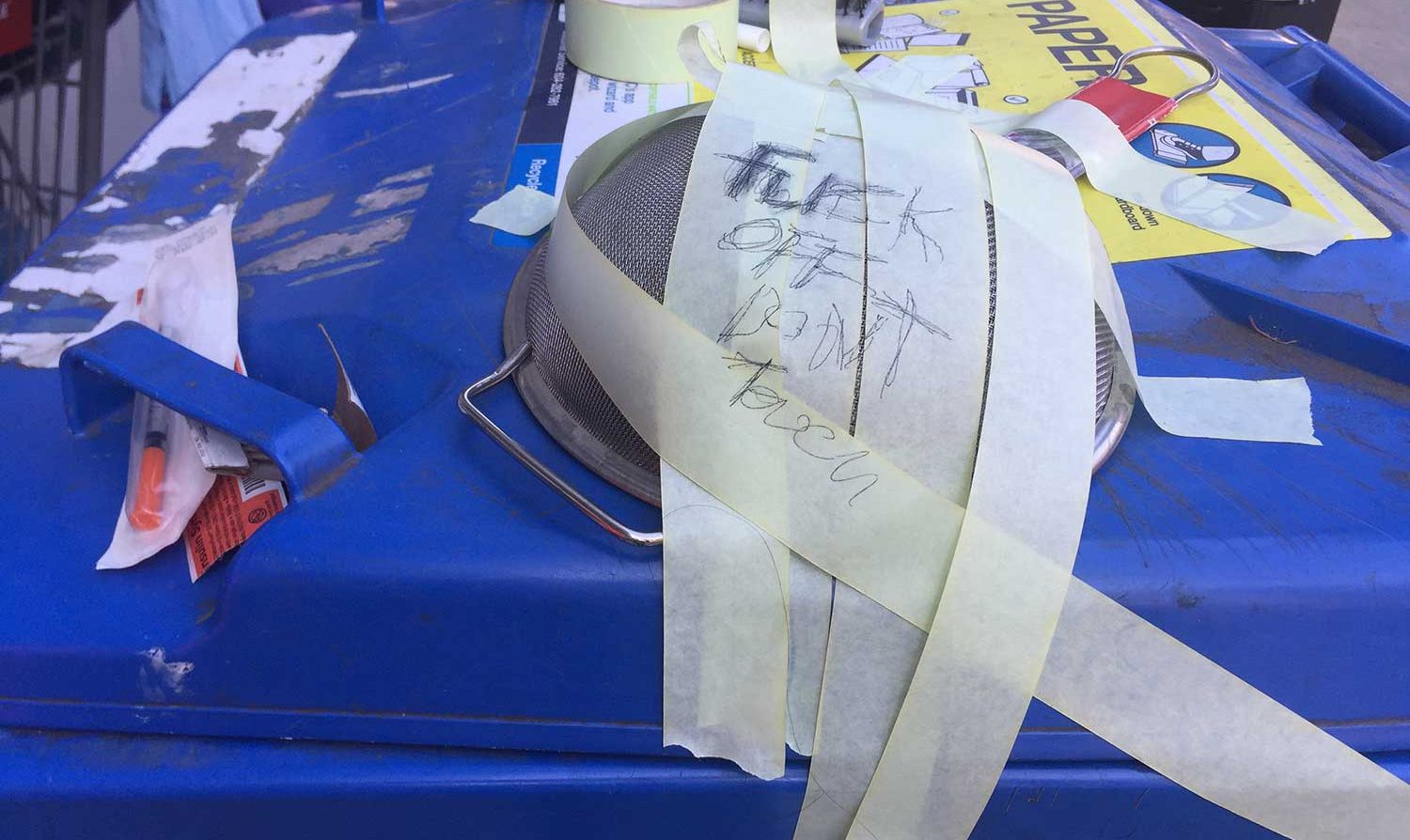

Fox is one of 2,138 sleeping rough in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. The DTES is ground zero for charities, social services, and government agencies; a living ‘case study’ of the ‘intractable’ ‘wicked’ and ‘complex’ social problems for which social innovation is so fervently espoused.

We do some of that espousing. We lament the status quo. We talk about the need for new thinking & new methods. But, if there is one thing I keep re-learning from the Foxes of the world, it’s that new thinking & methods can offer more ways to do the same. More ways to exclude. More ways to exert power. More ways to abdicate moral responsibility under the guise of complexity theory and systems thinking.

Yes, systems are big and complex. But they are also not the abstracted entities we make them out to be. They are composed of people – lots of them, who (often unknowingly) reproduce the dominant rules, routines, and relationships in their everyday behaviors and interactions. When an operations manager of a family charity furnishes their new building with a front desk and service window, they are reproducing a power divide between worker and family. When a case manager of a drop-in centre hands a new client a clipboard with a form to fill out, they are reinforcing that staff control the interaction. And when a programing coordinator for refugee services creates the monthly schedule with activities starting at 9 and ending at 5, they are reinforcing that the end user is staff, not refugees.

More human acts

Dismantling the dominant rules, routines, and relationships doesn’t have to be a grandiose act. On our first day in Vancouver, four years ago, we jumped into the car with a chief executive of a large disability organization with over 500 staff. We couldn’t go a block without him rolling down the window to say hello to a community member. He knew the names and birthdays of seemingly every person they supported – and had stories of camping trips, meals, and parties that sounded genuinely joyful for both.

Knowing the names and stories of the people you support isn’t an act of innovation. It’s an act of humanness. And we desperately need more humanness.

The current ‘brand’ of social innovation – of social labs, design thinking, systems mapping, business model canvassing, etc. – doesn’t ask enough from us. It doesn’t ask us to leave the room and re-set our everyday relationships with people living the social ‘problems’ we’ve decided to solve. It uses tools and frameworks as a substitute for whole hearted engagement, and keeps basic premises largely untouched. We don’t need more user-centered ways to do what we already do. We don’t need a better intake process or a better value proposition for integrated case management. Instead, we need to contest why we do intake and case management in the first place. We need to commit to tearing down the barriers we put up between systems and people, and re-formulating some of the big 20th century concepts that separate us – like professional boundaries and scientific management.

Over the past year, we’ve seen beautiful examples of humanness. They came from Sammy, a convenience store owner in Edmonton, who creates space for folks on the streets in his store. They came from Alex, a security guard in a Surrey social housing complex, who is a patient listener long outside of social worker’s office hours. They came from Leanne, a pharmacist creating moments of delight for methadone users and showing them they do matter. They came from Donna, a receptionist at a walk-in clinic who calls to talk to lonely older folks in the area.

Integrity in practice

Sammy, Alex, Leanne, and Donna have helped us to recognize an ingredient missing from much of the innovation discourse and practice – integrity. Integrity is a loaded word, we know. There’s lots of definitions. Stanford’s Encyclopedia on Philosophy sets out integrity as self-integration, integrity as standing for something, and integrity as moral purpose.

“To live with integrity is not merely to have a coherent life-plan and the courage to realise it, it is to act in a way that is rationally endorsed both by oneself as one acts and one’s future self. To do this, one must act on principles and these principles must be such that they would be rationally endorsed by any future self who reflects on the matter satisfactorily.”

We’re starting to realize that what matters to us is creating conditions for integrity, not conditions for innovation. And we think that requires forging partnerships with the people who are quietly circumventing social norms and power hierarchies. For us, that means spending less time in the social innovation community and within organizations who want to do what they already do, better. It means working at a smaller unit of scale, and supporting the Foxes and the Sammy’s to make more human moments with us.

Since InWithForward came to Canada, we’ve made social services our unit of focus. We’ve focused on building their capacity to re-invent what they do. But, our bigger goal has always been to rewrite the social contract – to establish new norms, expectations, and relationships between people, community, and the state. We’re no longer convinced we can get to there within organizations – but perhaps through organizations, with organizations as a different kind of vehicle.

At least that’s the provocation we’re wrestling with this week. As always, stay tuned.