There is not much infrastructure behind the 19,000 non-profits that comprise the Canadian social safety net. We can think about infrastructure as the structures and processes that enable households and organizations to operate and to develop.

Yes, organizations in Canada have access to water, to electricity, and to Internet. This keeps the doors open, the lights on, and the computers (mostly) operating. But the pressure to reduce overhead costs has prevented many organizations from building the kind of infrastructure required to not only deliver care, but to advance their broader social missions. This is a kind of human infrastructure – it’s the time, the talent, the data, and the networks – to illuminate what’s not working, to cook up alternatives, and to move practice from here to there.

Take a managerial building block as banal as staff meetings. For most of the organizations we work with, frontline staff meetings are a luxury. These are big non-profits with hundreds of workers out in the field, in homes, on streets, in day programs, and drop-in centres. Their underpinning structures and processes have largely been built for compliance. What little time workers have together is spent reviewing health and safety protocols and meeting basic care standards. They have few underpinning structures and processes for continual development. So they work within their old operating systems, without the bandwidth to confront stale paradigms and outdated practices. Just like our bricks and mortar infrastructure is no match for the virility of Mother Nature, our organizational infrastructure is no match for the stubbornness of our toughest social challenges.

Innovation without infrastructure

Over the past decade, social innovation has emerged as a field aspiring to tackle social complexity. And while it’s offered us a language for diagnosing some of the problems, it’s (so far) failed to give us robust technologies for building new organizational ground. Labs, hackathons, un-conferences, world cafes, and even social impact bonds are programmatic add-ons. They don’t fashion the kind of workforce, intelligence systems, or partnerships required to both develop and operate alternatives to the status quo. Without also investing in core infrastructure, innovation projects will always remain short-lived pilots and fading fads.

Introducing Grounded Space

That’s why we’ve spent much of 2017 trying to build organizational infrastructure. Thanks to the generosity of the McConnell and Conconi Foundations, we launched Grounded Space, Canada’s first collective of social service agencies dedicated to making development a core function alongside program delivery.

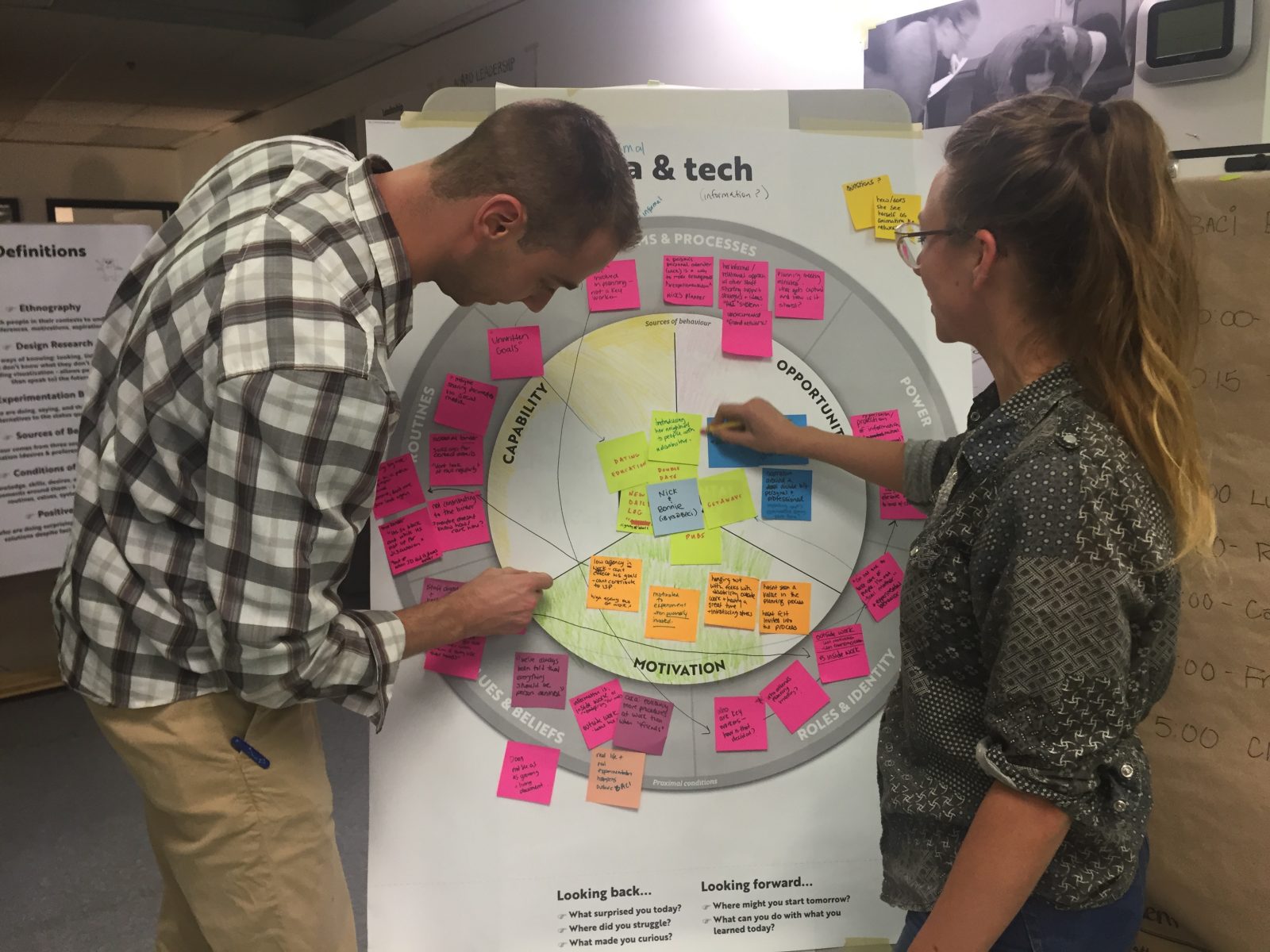

Our first four members have set-up new roles (Culture Curators), new teams (Embedded Research teams), new routines (huddles, reflections, debriefs), and new ways of collecting and feeding back qualitative data. Rather than direct organizational energy towards short-term projects, we’re focused on creating the cultural conditions that enable new practices to continuously emerge and to stick. That’s meant creating staff positions that realign typical hierarchical relationships; re-wiring flows of information from the bottom to the tops of organizations; and spreading stories of change and positive exceptions.

We’re definitely having to learn how to use different machinery. As a team of makers, we’re stumbling our way into the builder business. Makers tinker and try. We mock up ideas quickly. We fail quickly. We iterate quickly. Builders take a longer-term view. They measure. They plan. They construct things so they’ll last. We’re attempting to figure out how to erect lasting human infrastructure with agility, that can enable the continual re-making of practice.

Imagine organizations – with embedded research teams comprised of new staff on their first month of orientation, older staff on yearly rotations, and core staff recruited for their background and skills – continuously surfacing insights about what’s happening on the ground for users and generating fresh ideas that can be tested in partnership with other organizations, families, community members, designers, coders, etc. This is the kind of infrastructure – the pipelines of intelligence, of ideas, and of talent – we think are necessary for social change.

Want to read more about our take on organizational infrastructure? Thanks to Employment and Social Development Canada, we published a paper called Develop and Deliver: Making the Case for Social R&D Infrastructure. Pair it with Bryk and Gomez’s terrific Ruminations on Reinventing R&D Capacity for Education.