Categories

I first arrived at the shed (our affectionate name for the InWithForward studio) on a Tuesday morning, emerging from a whirlwind of sleepless nights and cancelled flights. Within the first few minutes, I found myself immersed in an entirely different type of whirlwind – one of excitement, passion, and a jump-right-in mentality quite foreign to my inexperienced intern self.

Now, having been here for two months, I’ve begun to settle into a “rhythm” (in the sense that I’m certain each new day will bring completely unexpected challenges and work). I’ve also had the opportunity to reflect on what it means to overcome the gap between safety and flourishing in the social service world.

The Soul: Defining Grounded Space

The traditional consulting agency has a tried-and-true process. They partner their clients with subject-matter specialists, leading to expert driven insights and solution ideas. This process in inarguably profitable; hundreds of global consulting firms have been built in the last century, and private companies in particular have reaped monetary benefits [Financial Times].

We’ve tried this approach in the social sector across Australia, Europe, and Canada – but the results haven’t been as promised. While the work certainly has impact, we’ve found it difficult to make our programs stick long-term. The profit incentive that drives traditional companies is not as profound in non-profit services, and work is the social sector is far more reliant on a key unpredictable factor: people.

Reflecting on our experience, we came to the realization that change often isn’t sustained because it isn’t driven from the bottom up. EDs, senior managers, and outside consultancies have an idea of what change they think is needed, but fail to bring it back down to the user and staff understanding of that problem. Have the staff tried this before? Do they recognize this as a problem? Is there a desire to implement a change in practice or delivery?

I find this a compelling aspect of ethnographic research that’s gone substantially untapped in the social design world. The rise of design thinking in the 1990s did an incredible job of bringing the focus on product and service back to the user – where it had strayed substantially from in the past. Now, with the rise of social innovation – what I see as the application of a modified design thinking process to the larger social services field – it’s time to build out our user focus to account for all “users” – not just for the persons served, but everyone involved in the service.

Entering InWithForward, I hadn’t really considered these limitations of design thinking when launching considering larger-scale change. My own experience has centered on smaller-scale projects, which simply aren’t as contingent on long-term buy-in. Yet this experience forced me to reflect on the difficulty of launching systemic change – particularly, how my personal projects are limited in scope because they don’t take full advantage of the potential stakeholder support.

Moreover, I find this new perspective on sustained impact through staff poses an even stronger statement on design thinking. We have progressively moved toward a culture of singular workshops and trainings to introduce newcomers to the field. Such a teaching style, while valuable in providing exposure, simply cannot support the process of enacting the ideas that might surface. The staff teams serving the most vulnerable people supported through social services don’t have the design thinking background. Reframed, the people that have the capacity to enact the most change don’t have the training or culture to do it.

This kind of difficulty rises particularly in the social sector because it lacks an in-house research and development that has the capacity to think in this way. In a non-profit environment where funding is contingent on face-to-face hours with people served, essentially no money is earmarked for this kind of R&D capacity. Yet our experience have shown us that this model won’t work if our goal is sustained, user-centered change.

Such a situation begs the question: what kind of system provides nonprofits with the capacity to consistently research, develop, and implement lasting innovations?

A Quick Anecdote

This past year, in my class entitled “Play to Innovation”, I had the opportunity to learn from John “Cass” Cassidy. A chuckling, baseball-capped teacher and prolific children’s book writer, he reserved a class to teach us his formula for creativity.

A formula? How could something inherently beyond logic be defined in a logical sense?

His trusty “protocol to be creative” relies on the Flip180 rule – take a common situation, and turn one or more elements to its opposite. It starts simply – a man waiting patiently for the elevator rather than impatiently; but can progress beyond adjectives and verbs to nouns and mindsets. For example, to Flip180 a bull, we can select three things to describe it – strong, large, and aggressive – and choose the opposite for one characteristic. We flip aggressive to peaceful, and voila; it’s the best-selling book The Story of Ferdinand, a tale of a bull who’d rather smell flowers than fight in bullfights.

What does it mean to be an “anti-consultancy”?

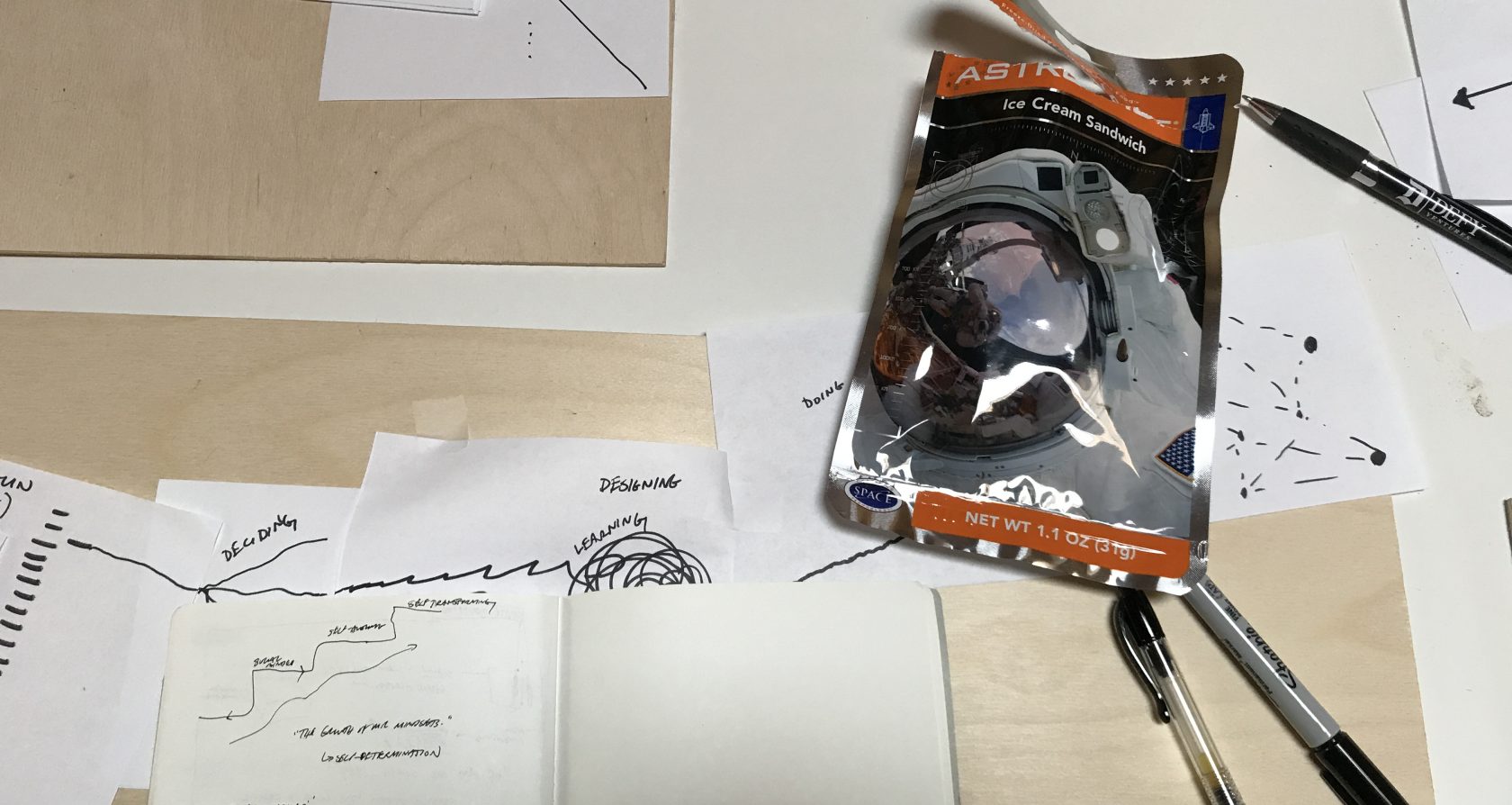

Grounded Space is a Research & Development collective. It supports teams of staff, individuals and families to collect data on the challenges they see, co-design, and implement solutions. Both the data and the solutions are shared between organizations, increasing the collective intelligence and capacity of the sector.

Grounded Space is an example of the Flip180 rule applied to a larger context. There is a very distinct shift in mindset that opposes the nature of most consultancy work. It’s coaching of staff & individuals in identifying and creating change themselves, rather than designing a solution from the outside. It’s forging partnership, rather than competition, between social service organizations working to support vulnerable people. It’s continuous creation and reflection, rather than one-time design sprints.

It’s far more of a marathon than a walk the park. The amount of time, money, and effort it takes to engrain this mindset in even a single organization is no small task – and often leads me to question if it’s worth it. I myself have concerns about the sustainability and funding model. But when these structures consistently exist (eventually) across social service organizations, I believe it will enable a drastic re-imagination and rediscovery of what the social sector looks like.

The Heart: Why we do what we do

The empathy-altruism hypothesis, developed by Daniel Batson in 1991, suggests that helping behavior is primarily based on empathy, with considerations of cost and reward at a much lower, secondary level. While this hypothesis was created as an explanation for voluntary helping, I feel it just scratches the surface of the underlying motivations.

In Spring 2014, InWithForward started Burnaby Starter Project in partnership with PosAbilities, BACI, and Kinsight, three established disabilities agencies in the Lower Mainland, Canada. They spent three months immersed in Stride Place, an integrated living community in which half the residents have a cognitive disability. They talked with nearly every resident – not just coming in for a few hours and leaving, but actually taking the time to form empowering relationships with a marginalized community. It is this kind of dedication – this willingness to create intimate friendship – that both inspires and speaks to the motivation behind this work.

Three years later, I had the opportunity to follow less rigorously in their footsteps. I’ve spent these past two months living at Stride, and while I wasn’t conducting an ethnography, it was a powerful time of engagement with a community I have little experience in. Never before had I had an opportunity to physically live with the people I designed for. It is particularly humanizing – a relationship beyond the researcher hat that lives beyond the success or failure of a project. I will remember Karen, Fay, Don and Michelle – not as people to be served, but as people with whom I shared stories and questions and laughter.

These times of genuine engagement drive at the core of ‘why this work?’ As a child, I had a prevalent shyness and deep sense of justice. I felt caught in between a feeling of needing to help and a fear of communication. It led to quiet insistence to engage in the traditional kind of service – food banks, homeless shelters, tree planting, and more. As I approached teenage-hood, I found myself intrigued by the concept of designing in social good – taking simply volunteering and pushing people to think critically about how we create a larger impact. I ran with the idea – forming a team of students who were excited about different social causes, and creating local projects run on idealism and grounded in reality. Design and development and delivery enabled my need to serve to overcome my deeper fears.

Of course, not every team member has the same story – yet key similarities emerge as you push further. There is a sense of duty, and openness to change, and a willingness to be vulnerable. Honesty around what we feel and need. And a genuine mission-driven mentality that enables the strongest work ethic of anywhere I’ve seen.

Towards Flourishing

As my time here comes to an end, I’ve felt the need to reflect on the larger mission of InWithForward: turning social safety nets into trampolines. In itself, this is a revolutionary concept that rethinks the modern welfare state.

Grounded Space is the first step. It’s neither easy nor fast; yet it is critical if we are to move past the comfortable rut of stagnation and predictability. And as we continue to immerse ourselves in this world – and in our mission to provide the people working in the social sector with the capacity to create their own innovations – we must always come back to the Karens and Dons and Michelles to center ourselves and center what we create.

I think Cass said it best: “the opposite of my point of view, is yours.”