Categories

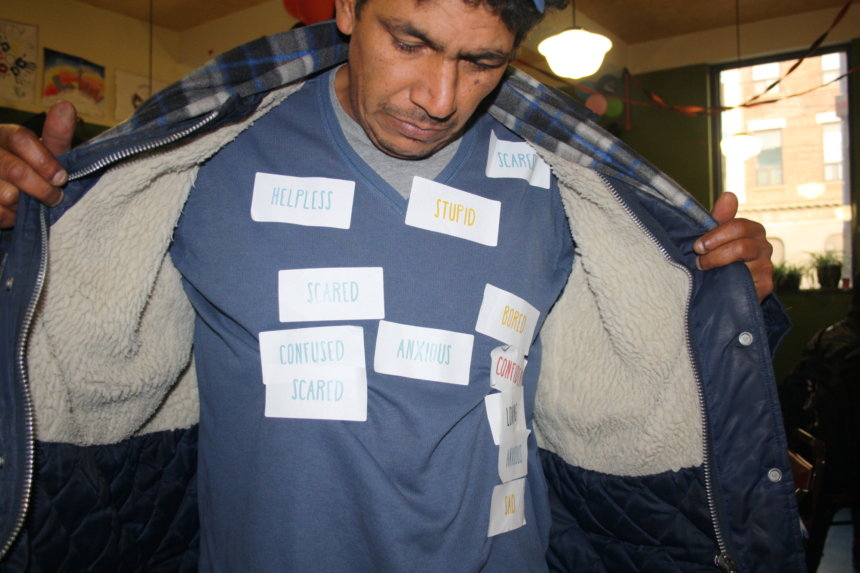

Carlos was giving, earnest, and in a context where weakness could be a perceived liability, vulnerable. He shared his feelings. Sad in one moment. Elated in the next. He was the first to test our UforU podcasts – designed to bring moments of relaxation, beauty, and intellectual stimulation to a volatile and unpredictable environment.

Our In/Out project was set-up to understand the uptick of deaths in 2014-2015. Two years later, the death toll is still climbing and we’re left asking: how do we innovate when the crosswinds preventing change are so powerful? We talk a lot about innovation coming from the margins. But, what happens when the margins are so extreme? When…

- Drugs are easily accessible, increasingly potent, and relatively cheap.

- Housing is expensive. Benefits are stagnant.

- Funding for basic shelter & health care services are cut.

- Trauma, grief, and loss of self accrue at a staggering pace.

- Fear and stigma are rooted in many communities and ‘Not in my backyard’ is a refrain.

- Staff spend upwards of 65% of their time fighting fires, and have little energy or appetite for change?

Given the stark reality, prototyping new interactions can seem so small. Would it have been better to spend project monies on housing 30 people for a year? Or did it make sense to experiment with 10 ways to inject something other than drugs and alcohol into the every day? That meant we …

- Developed a conversational card deck using narrative therapy techniques for use in busy drop-in centre environments

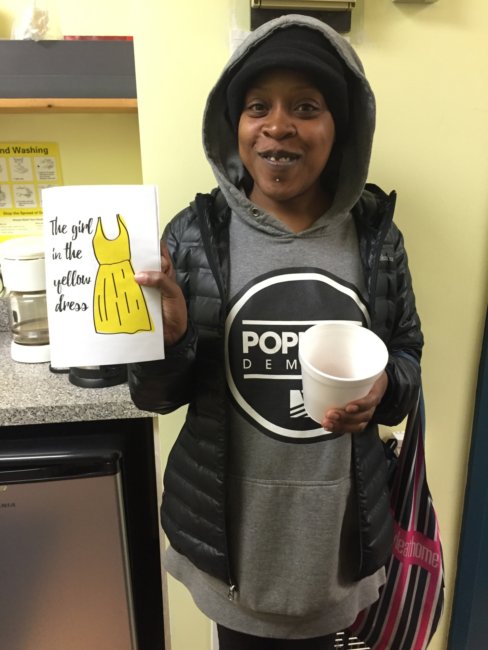

- Played back people’s own stories of change as illustrated storybooks and physical objects

- Created a ‘vending machine’ for the mind – with DIY podcasts, poetry, crafts, games

- Ran pop-up salon sessions & lectures with local concert violinists, philosophers, animators, neuroscientists, etc.

Brokered relationships with local art galleries and museums to create lovely moments of reprieve - Offered new kinds of roles for drop-in centre members (e.g comedian in residence, interior designers)

- Engaged local business folk to see another side of drop-in centre members

- Tried new ways of measuring mood and readiness to change each morning

- Developed a format for capturing observational data from street-involved adults for policymakers

- Coached staff to tweak small interactions within their control (e.g addiction support groups)

We did witness some early indicators of change – though these changes were more staccato than legato. Amongst the street-involved adults with whom we worked most closely, we heard more change talk, increased agency, greater consideration of alternative possibilities, and widened outcome expectations. Amongst the 30 community members we worked with, we saw shifts in their perceptions of street-involved adults and willingness to engage. We believe more positive human-to-human interactions are what underpin bigger systemic and electoral reforms.

Reverse effects

And yet, amongst drop-in centre staff, we too often had a reverse effect. Fear, anxiety, defensiveness, and friction were common reactions. While a year later, there are new drop-in centre roles with experimentation in the job description, survival remains the pervasive focus. It matters less what’s in the job description than what the context demands. And grief, exhaustion, and skepticism are the contextual mainstays. We didn’t just make visible the people already on the margins. We also created a new margin, made-up of weary frontline staff.

Lately, the disconnect between the bombastic language of innovation and these weary frontline staff has felt a little absurd. The innovation field – social innovation included – has made little room for the stories of the ‘losers’ of innovation. They have little to say about the unintended harm created. Of the 50 most innovative companies featured in the recent edition of Fast Company, most are upending traditional markets. Their disruptiveness is precisely what makes them so impactful. And yet the mom and pop grocery stores that may be affected by Amazon’s foray into bricks and mortar retail are unseen and unheard in the narrative.

We strongly believe in disrupting the traditional social welfare state. At the same time, we recognize that the 104,000 frontline social service workers in Canada cannot be marginalized in the process. The American election is a stark reminder of what happens when a group left marginalized by economic innovation and rapid social change feels unseen and unheard.

But the institutions that have the most to lose (and gain) from transforming the welfare state – the frontline workers, the social service delivery organizations, the unions, the accreditors, the licensors, the vocational colleges – are largely left out of the social innovation narrative. They aren’t in the room at the social innovation conferences, which are increasingly inhabited by the consultancies and the intermediaries. They aren’t shaping the language. They aren’t co-owning the agenda. So why should we be surprised when our entreaties for change engender resistance and protectionism?

Building infrastructure

We think it’s time to address the resistance and protectionism head-on. We think it’s time to recognize that what social innovation really asks of people is to re-define parts of their identity – to embrace new types of relationships, to be ok with not knowing the answer, to question themselves, to re-wire an old habit, etc. Even when we ask people do to something seemingly simple – to adopt a new technology as part of their work – we might be overturning a deeply engrained routine that is wrapped up in people’s sense of confidence, comfort, and professionalism.

The question we’re grappling with is how do we get underneath the barriers to rewiring habit loops and redefining identities? How do we make innovation not just about groovy ideas but about creative implementation? Not just about novel products & services, but about grieving the loss of old ways of doing and creating space for novel ways?

These are just some of the barriers we’re hoping to directly do something about:

- No remit. Social services are set-up to deliver services and execute policies, not develop services or shape policies.

- No access to capital. Social services have access to project dollars, not dollars for retooling the workforce, IT investments, etc.

- Reverse accountabilities & incentives. Social services are accountable to funders and staff are accountable to bosses, not to end users or community members.

- External locus of control. Low agency and autonomy are all too common experiences for both staff and end users. Change is a hard ask when things already feel out of control.

- Not knowing. Beyond utilization rates, social services know very little about how end users and staff are faring. Staff know little about whether they are doing a good job. End users get little feedback about whether things are changing.

- Hierarchical organization of work. Social service are largely command and control structures, often with an adversarial dynamic between management and staff.

- Workforce make-up. Designers, programmers, anthropologists, etc. are missing from social services. Social services can’t attract or afford new kinds of talent.

- Quality improvement and professional development. These organizational functions consolidate one way of doing things, rather than offer alternative ways.

- Narrow reference points and bridging networks. There is little frontline access to lateral examples, practical theories, and transferrable practices.

- Limited communication channels. The social welfare workforce is distributed in people’s homes and communities. They are hard to reach. And not particularly tech enabled.

Addressing this is what we’re calling infrastructure building. If our social services are going to be more dynamic and developmental than they need the same kind of investments we make on roads, bridges, and tunnels. In the absence of such investment, social services will do what they do well: survive. Innovation projects like In/Out might yield some promising practices. But little will stick. And the bigger social forces behind the rising death rates on the street will continue to feel insurmountable, underscoring the perception the little guys have no control.

Let’s use the control we do have and start building.