Categories

Family by Family was the product of this ground campaign – of weekends spent recruiting families in front of Coles grocery stores and week nights sharing chicken lo-mien with families of all shapes and sizes.

TACSI is now 50 people. That’s a lot of real jobs. Their growth legitimizes a core premise: start with people, work backwards from outcomes, and you can see change. But, change at what level? One of many unresolved questions for those of us in social innovation: do new programs like Family by Family lead to systems change? When and how?

TACSI has been in Canada this past week (thanks to SIG!) asking some similar questions. They are in the midst of iterating the Theory of Change for their work. So are we.

When I left TACSI at its low point – we were out of government money – I couldn’t shake the feeling that we were missing a trick. We’d invested a couple of million in the design of Family by Family, Weavers, and five other aged care solutions, but, I didn’t see how scaling innovative programs outside of delivery systems would prompt change inside of those systems.

How could we shape the thousands of social workers, aged care workers, and disability workers who are the actual boots on the ground, the organizational cultures in which they are entrenched, the authorizing environments and procurement policies, let alone the public’s expectations?

InWithForward formed out of impatience with results. We wanted to experiment with other routes into systems change. Our domestic violence work in The Netherlands had fallen into the same programmatic trap: nice ideas, with little system engagement.

We came to Canada with a revised hunch: systems change from the middle-up and middle-down. We would partner with the implementors – the service delivery providers – and use their leverage to mobilize people and policymakers. They had existing relationships with each part of the system – from families to frontline staff to unions to accreditation bodies to procurement officers to politicians. Could we, over time, prototype new roles & relationships?

At the beginning, we articulated our approach in terms of user-centered design. We quickly saw its methodological limits. When there are multiple user groups, with conflicting interests, who holds decision-making power? Ethics and politics are strikingly absent from mainstream design thinking discourse.

Ethnography (spending time with people in context), co-design, and prototyping are political acts. The questions you ask, the insights you extract, and the information you ignore are informed by how you see the world – the narratives, the theories, and the values you hold.

I believe one of the core innovations of Family by Family was shifting the frame: from child resiliency to family flourishing. Whereas the resiliency literature focused on bouncing back from trauma, the flourishing literature focused on bouncing forwards. This new frame was informed by spending time with the positive deviant families – but it’s genesis was our team’s value set, and the theories I chose to prioritize.

The same is true for Kudoz, the adult learning platform for adults with cognitive disabilities that InWithForward has co-developed and is now spreading with three visionary disability service providers in British Columbia (BACI, posAbilities, and SFSCL). Together, we’re shifting the frame from safety to growth mindset. Our starting value base is that adults with cognitive disabilities have the capacity to learn, reflect, and grow a sense of self & future.

New values and theories cannot always be layered on top of what’s already there. Often, they conflict. And yet that is typically what we do when we scale an innovative program. Funders purchase the product without buying the underpinning theoretical framework or returning parts of the status quo narrative.

The status quo narrative is one steeped in the morality of caring, rather than in the optimism of change. By that I mean, the dominant language is that of diagnosis and assessment, of separating those deserving of care from those not yet deserving. Care is expressed in terms of servicing immediate needs. The language of growth, development, and building capability to meet one’s own needs is either absent or an afterthought – the thing to be done after risks are mitigated.

This is particularly true in the adult service system, where the dominant theoretical base is based on outdated behavior change theories. These are largely theories which are about controlling observable behavior – rather than on how humans learn, interpret, sense-make, and shift course.

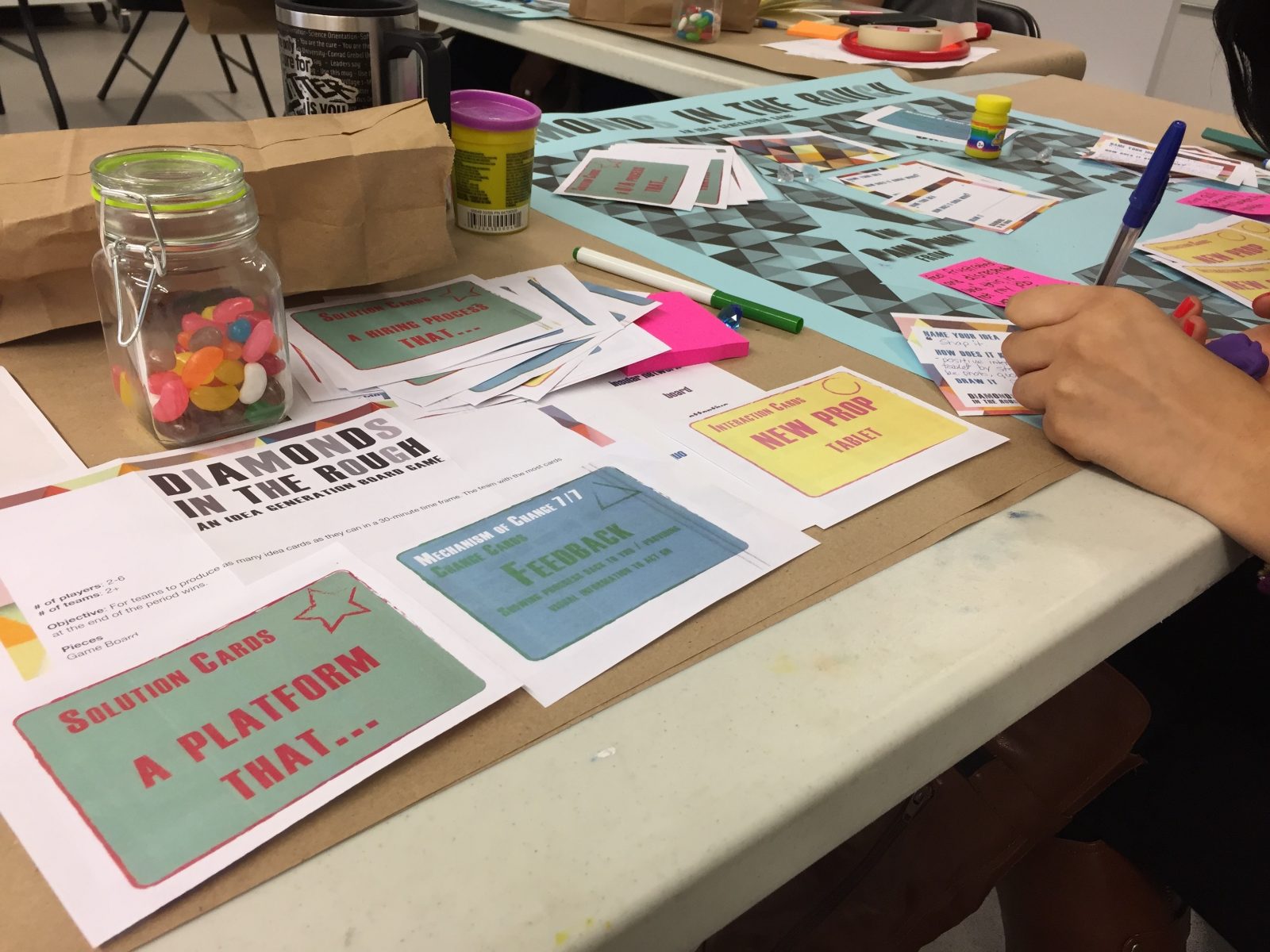

Over the past couple of years, InWithForward has begun experimenting with how to enable system leaders, managers, and frontline deliverers to recognize their own narratives, get introduced to new theory, and act from new ways of knowing and understanding. We’ve done this by conducting ethnographies of staff, providing in-context coaching, playing board games which introduce new theories, and generating scenarios from different theoretical bases.

It’s all still early days.

Over the coming two years as we grow and set our sights on bigger systems change, we’ll focus less on building system capacity to adopt innovation methods and more on capacity to try on new narratives. These will be narratives grounded in people’s lived experiences and nourished by a diverse set of theories – from neuroplasticity (check out how our Toronto work uses this) to social cognitive career theory (check out how Kudoz uses this).

We’ll be asking: how do we create a new kind of literacy in behavior change? At the same time, how do we curate the conditions for system actors to make literate decisions? We increasingly believe literacy in social innovation is distinct from literacy in human development.

So, stay tuned for ours – and TACSI’s – revised theories of change.