Categories

We’ve been trying to re-invent disability day programs, homeless drop-in centers, unemployment programs, and volunteering by simultaneously delivering services and developing new technologies & practices. But, we’ve been doing so from inside of existing social services. And we’re no venture capitalist darlings.

Our inside-out approach was intentional.

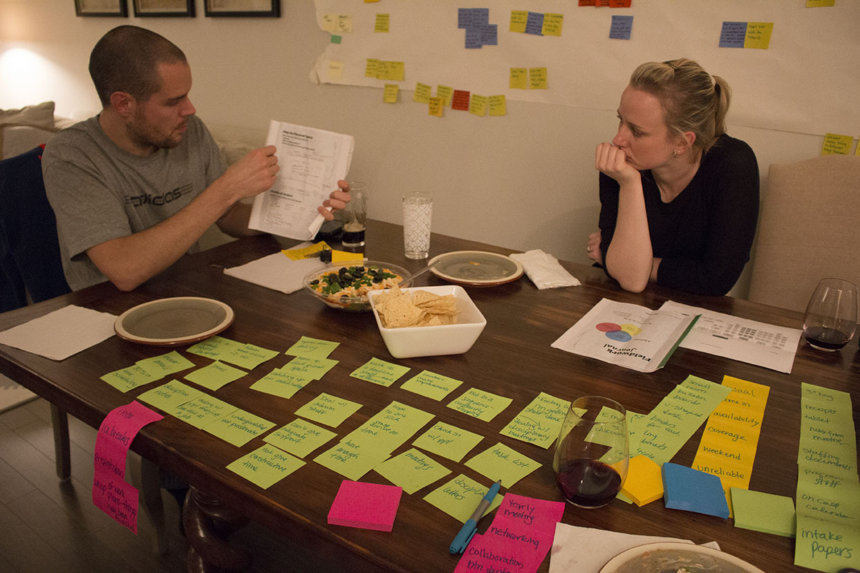

We came to Canada to test a hypothesis: social service deliverers can & should develop innovative new models; they have leverage up (to funders) and down (to users). All we needed to do was create a flagship example and build capacity.

Two years later, we have a fledgling flagship (Kudoz) and we’ve worked alongside 100 frontline, mid-level, and senior level directors to grow capability.

But, we haven’t really built capacity.

Capability and capacity are not the same thing.

Capability refers to the skills, knowhow, and mindset required to do innovation. We’ve enabled maybe half of those 100 workers to name problems, conduct ethnographic research, generate and test ideas – with most of their ideas equating to modest fixes of the status quo.

Capacity refers to how much space there is for those new skills, knowhow, and mindsets. It’s about whether there’s room to absorb new practice and adopt change.

There are a lot of ways to grow capability – webinars, toolkits, workshops, conferences, and special diploma programs among them.

Building capacity, on the other hand, takes freeing up existing resources plus adding novel resources. This might be hiring from a new discipline, reworking roles & responsibilities, shifting organizational structures, changing incentives & accountabilities, and devoting more time to change processes so they can be reasonably absorbed. And yet, spending more time mired in organizational politics can feel at odds with the innovation rhetoric of rapid prototyping and lean development.

Alt School moves quickly. And they can because they’ve started from scratch, very much outside of the existing school system. They’ve hired two separate teams – a development team and a delivery team – all comprised of people who chose change over stability. They could afford two separate teams because they have two (lucrative) revenue models. Their delivery team – the teachers and administrators – are funded through tuition ($26-30K/yr). The development team – the product designers and engineers – are funded through venture capital funds and foundations. School-aged kids and their parents are, after all, a huge and compelling market.

Adults with developmental disabilities, untreated mental health afflictions, chronic homelessness, and chronic addictions are neither a huge nor compelling market. They are however a huge and compelling cost to government.

Social innovators, with their sunny optimism, valiantly make the case for a social return on investment. Put money into the pot now for savings down the road. This is predicated on the idea that an upfront expense on innovation will create breakthrough models that can scale.

Problem is, there just isn’t the capacity for the current social sector to deliver innovation at scale. Throwing some money into innovation pots to get to a new model doesn’t address the ongoing resource required to do delivery and development well.

Care versus Change?

The existing social service workforce – the program workers, disability workers and home health care aides that are the real army of the welfare state – is rooted in a value set of care and stability. Not change and development. Indeed, the social care industry attracts people who “want to help” – but only equips them with 6-12 week courses, little ongoing professional development, and few career ladders. In demand and over worked, the constancy of a paycheck keeps many in the job, but too few able to put more into that job.

Against this backdrop, it’s no wonder so many of our capability building efforts fall flat. They are based on assumptions that we haven’t found to be widely shared at the front or mid-lines: that change is desirable; that passion has a place in the workplace; and that to be professional is to be discerning & generative, not cautious & risk adverse. Even where we’ve found senior directors and board members chomping on change, the part of the organization charged with implementation is in a bind. They can’t easily stop what they are doing and re-tool. Adults living on the streets still need their drop-in centre to be open. Disabled adults still need their support workers day-in and day-out. That leaves change work always sitting on top of other work.

Can change work ever become the work to done? Indeed, in the absence of a delivery team hired for their adaptiveness and a development team hired to guide change, what does good capacity and good capability building efforts even look like? Is it feasible to enable the existing workforce to go beyond continuous improvement, and recast their own purposes, roles, and tools?

We’ve got few other choices. There’s not a market for a parallel social service system. With the exception of short-term grants from foundations, nearly all of the money for social services is tied up within existing contracts. Innovation funds remain paltry – particularly for marginalized population groups with chronic (versus acute) challenges, where there is more of a moral than economic case for action.

We must make that moral case. At the same time, we can also bring together ‘early adopter’ organizational leaders with their mid-level managers and help them figure out how to run at least two operating systems at once. Just like the small-school movement took one institution and carved it up into separate entities with separate cultures, could we do the same with our drop-in centers and services? Might this enable a proliferation of alternative models?

Of course, doing so, brings us right back to values and ethics. Innovation runs counter to some of the beliefs of the social sector – namely, equity and fairness. To truly allow for alternative models to proliferate means walking away from a definition of equity as sameness. Innovators don’t try to be all things to all people. They find their niche. The pipe dream, then, is whether social service organizations can become a big enough platform that everyone can discover their niche.