Categories

We are overloaded daily with new discoveries, patents and inventions all promising a better life, but that better life has not been forthcoming

Whilst we’ve tried to distance ourselves from the false value neutrality of social innovation, the language has crept back in. There I was on Wednesday, describing to a group of frontline workers “innovative, new practice.”

Ugh.

A discerning manager approached to comment, “When I hear the word innovation, I don’t hear any appreciation of what’s been tried or what already works. It sounds like newness for the sake of newness, and I have to tell you, I bristle at it.”

It’s fair to say, we’ve put a number of managers’ backs up in the last six months. Where most consultancies keep the relationship to a summer fling or romantic honeymoon, InWithForward is the anti-consultant.

We move-in with all of our mess. Our stuff doesn’t neatly fit into your closets, and our $12 ikea stools (from the children’s department) don’t match the office decor. Nor do our routines quite align. Our pace exhausts. We’re up late iterating, when you thought we’d put the document to bed. Even more irritating, we want to explore big ideas when you’re in a rush to get to work before the traffic hits.

Strange bedfellows as we are, we’re not ready to call it quits.

We met our current partners two years ago. Tired of dating, InWithForward was seeking a more serious relationship. Our past relationships with service providers were tangential and transactional.

So far, our brave partners have included West Neighbourhood House, posAbilities, Burnaby Association for Community Inclusion, and Simon Fraser Society for Community Living.

In prior projects like Loops and Family by Family, service providers functioned more like distant relatives than close-knit partners. We gathered for periodic get-togethers, but had little day-to-day interaction. Our theory of change was from the outside-in. We operated as an independent organization on the outskirts of the social sector, first generating innovative programs and then implementing those programs. To scale, the organization grew its size.

That shifted when we moved to Canada, and adopted a theory of change that was from the inside-out. We embedded ourselves within existing social sector organizations to generate intentional tools (like Kudoz) & practices (like curious conversations). Now, we’re training community and staff to implement those tools & practices. To spread, we need to grow the sector’s capacity and shape their culture.

Although our theory of change shifted, perhaps our language and tactics have not. That’s why, over the next two years, we want to pause from project work and turn our attention to crafting the narrative and building the infrastructure for embedded change. We’ll start to sketch out a new methodology we’re calling values-led design.

Means and Ends

Where the word innovation focuses on the means, the word intentionality zeros in on the ends. An innovative product or service is novel in some way. An intentional product or service fulfills an explicit purpose. Since our work is about deliberately connecting means with ends, intentionality is a more meaningful descriptor.

We embed ourselves in contexts like homeless centers and disability day programs to identify gaps between where people are versus where they want to be. For us, design is about closing the want-do gap. Social science is about better understanding what it is people want. We use a philosophical framework around ‘flourishing’ to help us do that.

If only it were that simple.

What people want is rooted in what they know, what they believe, and what they think is possible. To date, we’ve used the word ‘outcomes’ to refer to people’s desired ends. But, this technical language obscures its moral basis. Outcomes are a statement of values.

The social psychologist Milton Rokeah defines values as, “an enduring belief that a specific mode of conduct or end state of existence is perennially and socially preferable to alternative modes of conduct or end states of existence.” Where values are statements of priority, outcomes don’t have to be.

No individual, family, manager, director, or funder has ever disagreed with ‘flourishing’ or ‘well-being’ as an outcome. They can hardly say they are against that. But, there are legitimate disagreements about the values that make-up a flourishing life and the conduct to get there.

This was underscored in one of my first ethnographies. I was riding along as Lidia, a seasoned social worker, drove to clients’ homes for unannounced visits. It took four forceful knocks for Karen to come to the door. Karen had just turned 19, and was under a child protection order for neglect. You could hear her little boy gleefully singing along to Bob the Builder. Lidia asked about their morning routine, praising her for preparing Cheerios for breakfast. They sat down to talk.

“Karen, where do you see you and your son a few months from now?” Karen smiled, and grabbed a brochure from a drawer. “I want us to travel together. I’ve always wanted to see other places, and I thought having a kid ended all of that for me, but he’s young enough that we can do it together!”

Lidia responded, “And how realistic do you think that plan is, Karen? Would you say that reflects sound judgement as a parent to take your child to unknown places?”

Karen’s shoulders dropped. “Uhm, well, my friend did it. She’s doing alright.”

In the car, after the visit, Lidia processed the interaction. “It just shows that she lives in this fantasy world, if she thinks she could travel and take care of her son. She had been getting her life in order, and now this. I have to question her judgement.”

For Lidia, a flourishing life was one of order and stability. For Karen, a flourishing life was one of adventure and exploration.

Could both values be accommodated? Could we design an intervention that fulfills Karen’s desire for adventure in an orderly way? Or could we design an intervention that fulfills Lidia’s desire for order in an adventurous way? Who has the power to decide which values take precedence?

Perhaps our most significant oversight in the last few months has not been giving adequate voice to these tensions, and not enabling each user group to truly feel heard. Under the naive cover of human centered design, we mostly surfaced end users’ preferences.

That is, we spent heaps of time listening to adults living on the street, adults living with a disability, and their families. We spent a whole lot less time making visible the values of frontline staff, mid-level managers, senior directors, board members, funders, and of course, our own InWithForward team.

Read our draft paper, Push & Pull

The paper makes visible some values at play in a Toronto drop-in centre.

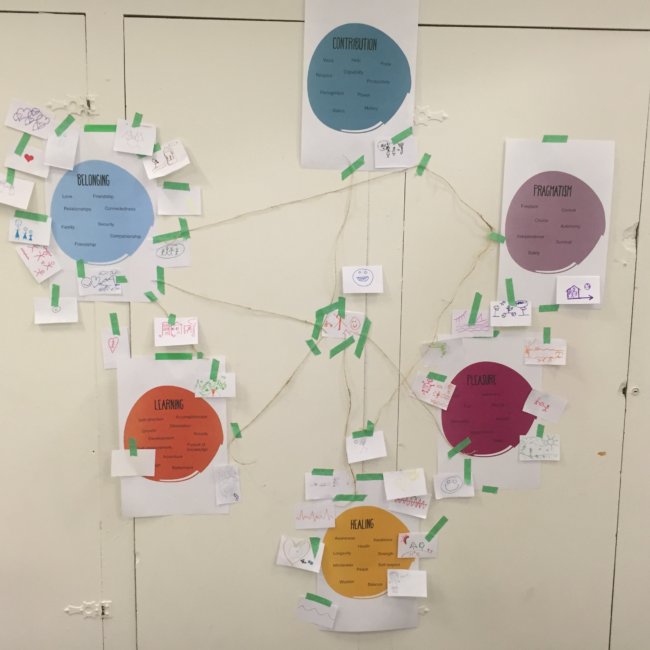

Last Wednesday, we started anew. Using Rockeah’s scale of terminal values, we asked about 50 staff of a multi-service organization to force rank their preferred end states and draw what was most important. End states around family, companionship, and collegiality trumped end states around adventure, learning, and challenge nearly 6:1.

How would knowing this earlier have influenced our approach to prototyping? Over the past many months, we’ve been experimenting with practices that prioritize challenge, learning, and discovery. And whilst few staff seem to be opposed to the ideas, they certainly aren’t valued as much as other things. So, what to do?

Here’s where our design methods fall woefully short. Design offers helpful tools for closing gaps between where we are now and where we want to be. But, there are few tools for mediating differences between where different groups want to be. Advertising and marketing has long been design’s lever of choice. Convince the consumer that they want or need something that maybe they don’t.

Still, the question remains: who should we be convincing? Do we convince individuals? Or their families? Or their frontline staff? Or mid-level managers? Or government funders? Or the public that elects government? Beyond advertising, what other levers do we have to expose people to alternative values and the concrete practices that fall from that? Can you really shift preferences? Or should services simply be more explicit and attract end users and staff with shared values? Do end users even have a choice over which services they use? Do staff?

Opening up conversations

This week, we’ll start contemplating these questions out in the open. Over the summer, we are coaching 10 practitioners in Toronto to explore gaps between their values & practices and between their end users’ values & practices.

We’ll work to move beyond the typical professional language of values (e.g person-centered, rights based, collaborative) to the meatier expression of terminal values (e.g pleasure, safety, love). How might we support a practitioner to have a conversation from another value base? What if Lidia had shared Karen’s preference for adventure, and encouraged the fulfillment of her value set? How might that conversation have played out?

This will be our bridge into Grounded Space, when we hope to start researching & testing ways to increase organizational readiness for disruptive intentionality. Rather than get managers’ backs up, we want to get their hands up, feeling heard and curious.